फोरट्रान - त्वरित गाइड

फोरट्रान ट्रांसलेटिंग सिस्टम से प्राप्त फोरट्रान, एक सामान्य प्रयोजन, अनिवार्य प्रोग्रामिंग भाषा है। इसका उपयोग संख्यात्मक और वैज्ञानिक कंप्यूटिंग के लिए किया जाता है।

फोरट्रान मूल रूप से वैज्ञानिक और इंजीनियरिंग अनुप्रयोगों के लिए 1950 के दशक में आईबीएम द्वारा विकसित किया गया था। फोरट्रान ने इस प्रोग्रामिंग क्षेत्र पर लंबे समय तक शासन किया और उच्च प्रदर्शन कंप्यूटिंग के लिए बहुत लोकप्रिय हो गया, क्योंकि।

यह समर्थन करता है -

- संख्यात्मक विश्लेषण और वैज्ञानिक गणना

- संरचित प्रोग्रामिंग

- अर्रे प्रोग्रामिंग

- मॉड्यूलर प्रोग्रामिंग

- सामान्य प्रोग्रामिंग

- सुपर कंप्यूटर पर उच्च प्रदर्शन कंप्यूटिंग

- ऑब्जेक्ट ओरिएंटेड प्रोग्रामिंग

- समवर्ती प्रोग्रामिंग

- कंप्यूटर सिस्टम के बीच पोर्टेबिलिटी की उचित डिग्री

फोरट्रान के बारे में तथ्य

फोरट्रान 1957 में आईबीएम में जॉन बैकस के नेतृत्व में एक टीम द्वारा बनाया गया था।

प्रारंभ में नाम सभी पूंजी में लिखा जाता था, लेकिन वर्तमान मानकों और कार्यान्वयन के लिए केवल पहले अक्षर की आवश्यकता होती है।

फोरट्रान फॉरमूला TRANslator के लिए खड़ा है।

मूल रूप से वैज्ञानिक गणना के लिए विकसित किया गया था, इसमें सामान्य उद्देश्य प्रोग्रामिंग के लिए आवश्यक चरित्र के तार और अन्य संरचनाओं के लिए बहुत सीमित समर्थन था।

बाद में विस्तार और विकास ने इसे उच्च स्तरीय प्रोग्रामिंग भाषा में पोर्टेबिलिटी की अच्छी डिग्री के साथ बनाया।

मूल संस्करण, फोरट्रान I, II और III को अब अप्रचलित माना जाता है।

अभी भी उपयोग में पुराना संस्करण फोरट्रान IV और फोरट्रान 66 है।

आज सबसे अधिक उपयोग किए जाने वाले संस्करण हैं: फोरट्रान 77, फोर्ट्रान 90 और फोरट्रान 95।

फोरट्रान 77 ने एक अलग प्रकार के रूप में तार जोड़े।

फोरट्रान 90 ने विभिन्न प्रकार के थ्रेडिंग, और प्रत्यक्ष सरणी प्रसंस्करण को जोड़ा।

विंडोज में फोरट्रान की स्थापना

G95 जीएनयू फोरट्रान मल्टी-आर्किटेकट्रेल कंपाइलर है, जिसका उपयोग विंडोज में फोरट्रान की स्थापना के लिए किया जाता है। विंडोज़ संस्करण विंडोज़ के तहत मिंगडब्ल्यू का उपयोग करके एक यूनिक्स वातावरण का अनुकरण करता है। इंस्टॉलर इसका ध्यान रखता है और स्वचालित रूप से विंडोज़ PATH चर में g95 जोड़ता है।

आप यहाँ से G95 का स्थिर संस्करण प्राप्त कर सकते हैं

G95 का उपयोग कैसे करें

इंस्टॉलेशन के दौरान, g95यदि आप "RECOMMENDED" विकल्प चुनते हैं, तो स्वचालित रूप से आपके PATH चर में जोड़ा जाता है। इसका मतलब है कि आप बस एक नया कमांड प्रॉम्प्ट विंडो खोल सकते हैं और कंपाइलर को लाने के लिए "g95" टाइप कर सकते हैं। आरंभ करने के लिए नीचे कुछ मूल आदेश खोजें।

| अनु क्रमांक | कमांड और विवरण |

|---|---|

| 1 | g95 –c hello.f90 Hello.f90 को hello.o नामक ऑब्जेक्ट फ़ाइल में संकलित करता है |

| 2 | g95 hello.f90 हेल्लो.f90 को संकलित करता है और इसे निष्पादन योग्य a.out बनाने के लिए लिंक करता है |

| 3 | g95 -c h1.f90 h2.f90 h3.f90 कई स्रोत फ़ाइलों को संकलित करता है। अगर सब ठीक हो जाता है, तो ऑब्जेक्ट फ़ाइलें h1.o, h2.o और h3.o बनाई जाती हैं |

| 4 | g95 -o hello h1.f90 h2.f90 h3.f90 कई स्रोत फ़ाइलों को संकलित करता है और उन्हें 'हैलो' नामक एक निष्पादन योग्य फ़ाइल से जोड़ता है। |

G95 के लिए कमांड लाइन विकल्प

-c Compile only, do not run the linker.

-o Specify the name of the output file, either an object file or the executable.एकाधिक स्रोत और ऑब्जेक्ट फ़ाइलों को एक ही बार में निर्दिष्ट किया जा सकता है। फोरट्रान फाइलें ".f", ".F", ".for", ".FOR", ".f90", ".F90", ".f95", ".F95", "में समाप्त होने वाले नामों से संकेतित होती हैं। f03 "और" .F03 "। एकाधिक स्रोत फ़ाइलों को निर्दिष्ट किया जा सकता है। ऑब्जेक्ट फ़ाइलों को भी निर्दिष्ट किया जा सकता है और एक निष्पादन योग्य फ़ाइल बनाने के लिए लिंक किया जाएगा।

एक फोरट्रान कार्यक्रम एक मुख्य कार्यक्रम, मॉड्यूल और बाहरी उपप्रोग्राम या प्रक्रियाओं की तरह कार्यक्रम इकाइयों के संग्रह से बना है।

प्रत्येक प्रोग्राम में एक मुख्य प्रोग्राम होता है और इसमें अन्य प्रोग्राम यूनिट शामिल हो सकते हैं या नहीं भी हो सकते हैं। मुख्य कार्यक्रम का वाक्य विन्यास इस प्रकार है -

program program_name

implicit none

! type declaration statements

! executable statements

end program program_nameफोरट्रान में एक सरल कार्यक्रम

आइए एक प्रोग्राम लिखें जो दो नंबर जोड़ता है और परिणाम प्रिंट करता है -

program addNumbers

! This simple program adds two numbers

implicit none

! Type declarations

real :: a, b, result

! Executable statements

a = 12.0

b = 15.0

result = a + b

print *, 'The total is ', result

end program addNumbersजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

The total is 27.0000000कृपया ध्यान दें कि -

सभी फोरट्रान प्रोग्राम कीवर्ड से शुरू होते हैं program और कीवर्ड के साथ समाप्त होता है end program, कार्यक्रम के नाम के बाद।

implicit noneकथन कंपाइलर को यह जांचने की अनुमति देता है कि आपके सभी चर प्रकार ठीक से घोषित किए गए हैं। आपको हमेशा उपयोग करना चाहिएimplicit none हर कार्यक्रम की शुरुआत में।

फोरट्रान में टिप्पणियाँ विस्मयादिबोधक चिह्न (!) के साथ शुरू होती हैं, क्योंकि इसके बाद के सभी वर्ण (एक वर्ण स्ट्रिंग को छोड़कर) संकलक द्वारा अनदेखा किए जाते हैं।

print * कमांड स्क्रीन पर डेटा प्रदर्शित करता है।

प्रोग्राम को पठनीय रखने के लिए कोड लाइनों का इंडेंटेशन एक अच्छा अभ्यास है।

फोरट्रान अपरकेस और लोअरकेस अक्षर दोनों की अनुमति देता है। फोरट्रान को छोड़कर, फोरट्रान केस-असंवेदनशील है।

मूल बातें

basic character set फोरट्रान में शामिल हैं -

- अक्षर A ... Z और a ... z

- अंक 0 ... 9

- अंडरस्कोर (_) वर्ण

- विशेष वर्ण =: + रिक्त - * / () [],। $ '! "% &? <>

Tokensमूल चरित्र सेट में पात्रों के बने होते हैं। एक टोकन एक कीवर्ड, एक पहचानकर्ता, एक स्थिर, एक स्ट्रिंग शाब्दिक या एक प्रतीक हो सकता है।

प्रोग्राम स्टेटमेंट टोकन से बने होते हैं।

पहचानकर्ता

एक पहचानकर्ता एक चर, प्रक्रिया या किसी अन्य उपयोगकर्ता-परिभाषित आइटम की पहचान करने के लिए उपयोग किया जाने वाला नाम है। फोरट्रान में एक नाम निम्नलिखित नियमों का पालन करना चाहिए -

यह 31 वर्णों से अधिक लंबा नहीं हो सकता।

यह अल्फ़ान्यूमेरिक वर्णों (वर्णमाला के सभी अक्षर, और अंक 0 से 9) और अंडरस्कोर (_) से बना होना चाहिए।

नाम का पहला वर्ण अक्षर होना चाहिए।

नाम केस-असंवेदनशील हैं

कीवर्ड

कीवर्ड विशेष शब्द हैं, जो भाषा के लिए आरक्षित हैं। इन आरक्षित शब्दों का उपयोग पहचानकर्ता या नाम के रूप में नहीं किया जा सकता है।

निम्न तालिका, फोरट्रान कीवर्ड सूचीबद्ध करती है -

| गैर-I / O कीवर्ड | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| allocatable | आवंटित | असाइन | असाइनमेंट | ब्लॉक डेटा |

| कॉल | मामला | चरित्र | सामान्य | जटिल |

| शामिल | जारी रखें | चक्र | डेटा | पुनःआवंटन |

| चूक | कर | दोहरी सुनिश्चितता | अन्य | और अगर |

| कहीं | अंत ब्लॉक डेटा | अंत करो | अंत समारोह | अगर अंत |

| अंत इंटरफ़ेस | अंत मॉड्यूल | अंतिम कार्यक्रम | अंत का चयन करें | अंत उपरांत |

| अंत प्रकार | अंत कहाँ | प्रवेश | समानक | बाहर जाएं |

| बाहरी | समारोह | के लिए जाओ | अगर | अंतर्निहित |

| में | अंदर बाहर | पूर्णांक | इरादा | इंटरफेस |

| स्वाभाविक | मेहरबान | लेन | तार्किक | मापांक |

| नाम सूची | मंसूख़ | केवल | ऑपरेटर | ऐच्छिक |

| बाहर | पैरामीटर | ठहराव | सूचक | निजी |

| कार्यक्रम | जनता | असली | पुनरावर्ती | परिणाम |

| वापसी | सहेजें | मामले का चयन करें | रुकें | सबरूटीन |

| लक्ष्य | फिर | प्रकार | प्रकार() | उपयोग |

| कहाँ पे | जबकि | |||

| I / O संबंधित कीवर्ड | ||||

| बैकस्पेस | बंद करे | endfile | प्रारूप | पूछताछ |

| खुला हुआ | प्रिंट | पढ़ना | रिवाइंड | लिखो |

फोरट्रान पांच आंतरिक डेटा प्रकार प्रदान करता है, हालांकि, आप अपने स्वयं के डेटा प्रकार भी प्राप्त कर सकते हैं। पाँच आंतरिक प्रकार हैं -

- पूर्णांक प्रकार

- वास्तविक प्रकार

- जटिल प्रकार

- तार्किक प्रकार

- चरित्र प्रकार

पूर्णांक प्रकार

पूर्णांक प्रकार केवल पूर्णांक मान रख सकते हैं। निम्नलिखित उदाहरण सबसे बड़ा मूल्य निकालता है जो एक सामान्य चार बाइट पूर्णांक में आयोजित किया जा सकता है -

program testingInt

implicit none

integer :: largeval

print *, huge(largeval)

end program testingIntजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

2147483647ध्यान दें कि huge()फ़ंक्शन सबसे बड़ी संख्या देता है जिसे विशिष्ट पूर्णांक डेटा प्रकार द्वारा आयोजित किया जा सकता है। आप बाइट्स की संख्या का उपयोग करके भी निर्दिष्ट कर सकते हैंkindविनिर्देशक। निम्न उदाहरण यह प्रदर्शित करता है -

program testingInt

implicit none

!two byte integer

integer(kind = 2) :: shortval

!four byte integer

integer(kind = 4) :: longval

!eight byte integer

integer(kind = 8) :: verylongval

!sixteen byte integer

integer(kind = 16) :: veryverylongval

!default integer

integer :: defval

print *, huge(shortval)

print *, huge(longval)

print *, huge(verylongval)

print *, huge(veryverylongval)

print *, huge(defval)

end program testingIntजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

32767

2147483647

9223372036854775807

170141183460469231731687303715884105727

2147483647वास्तविक प्रकार

यह फ्लोटिंग पॉइंट नंबर्स को स्टोर करता है, जैसे 2.0, 3.1415, -100.876, आदि।

परंपरागत रूप से दो अलग-अलग वास्तविक प्रकार हैं, डिफ़ॉल्ट real टाइप करें और double precision प्रकार।

हालांकि, फोरट्रान 90/95 वास्तविक और पूर्णांक डेटा प्रकारों की सटीकता पर अधिक नियंत्रण प्रदान करता है kind विनिर्देशक, जिसे हम संख्याओं के अध्याय में अध्ययन करेंगे।

निम्न उदाहरण वास्तविक डेटा प्रकार के उपयोग को दर्शाता है -

program division

implicit none

! Define real variables

real :: p, q, realRes

! Define integer variables

integer :: i, j, intRes

! Assigning values

p = 2.0

q = 3.0

i = 2

j = 3

! floating point division

realRes = p/q

intRes = i/j

print *, realRes

print *, intRes

end program divisionजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

0.666666687

0जटिल प्रकार

इसका उपयोग जटिल संख्याओं के भंडारण के लिए किया जाता है। एक जटिल संख्या में दो भाग होते हैं, वास्तविक भाग और काल्पनिक भाग। दो लगातार संख्यात्मक भंडारण इकाइयां इन दो भागों को संग्रहीत करती हैं।

उदाहरण के लिए, जटिल संख्या (3.0, -5.0) 3.0 - 5.0i के बराबर है

हम नंबरों के बारे में अधिक विस्तार से चर्चा करेंगे, संख्या अध्याय में।

तार्किक प्रकार

केवल दो तार्किक मूल्य हैं: .true. तथा .false.

चरित्र प्रकार

चरित्र प्रकार पात्रों और तारों को संग्रहीत करता है। स्ट्रिंग की लंबाई को लेन स्पेसियर द्वारा निर्दिष्ट किया जा सकता है। यदि कोई लंबाई निर्दिष्ट नहीं है, तो यह 1 है।

For example,

character (len = 40) :: name

name = “Zara Ali”भाव, name(1:4) "Zara" को विकल्प देना होगा।

प्रभावशाली टाइपिंग

फोरट्रान के पुराने संस्करणों में अंतर्निहित टाइपिंग नामक एक सुविधा की अनुमति है, अर्थात, आपको उपयोग करने से पहले चर घोषित करने की आवश्यकता नहीं है। यदि एक चर घोषित नहीं किया जाता है, तो इसके नाम का पहला अक्षर इसके प्रकार को निर्धारित करेगा।

I, j, k, l, m या n से शुरू होने वाले परिवर्तनीय नाम पूर्णांक चर के लिए माने जाते हैं और अन्य वास्तविक चर होते हैं। हालाँकि, आपको सभी वेरिएबल्स को घोषित करना होगा क्योंकि यह अच्छा प्रोग्रामिंग अभ्यास है। उसके लिए आप अपने कार्यक्रम की शुरुआत वक्तव्य से करें -

implicit noneयह कथन अंतर्निहित टाइपिंग को बंद कर देता है।

एक चर कुछ भी नहीं है लेकिन एक भंडारण क्षेत्र को दिया गया नाम है जो हमारे कार्यक्रमों में हेरफेर कर सकता है। प्रत्येक चर में एक विशिष्ट प्रकार होना चाहिए, जो चर की स्मृति के आकार और लेआउट को निर्धारित करता है; मूल्यों की सीमा जो उस मेमोरी में संग्रहीत की जा सकती है; और परिचालनों का सेट जो चर पर लागू किया जा सकता है।

एक चर का नाम अक्षरों, अंकों और अंडरस्कोर वर्ण से बना हो सकता है। फोरट्रान में एक नाम निम्नलिखित नियमों का पालन करना चाहिए -

यह 31 वर्णों से अधिक लंबा नहीं हो सकता।

यह अल्फ़ान्यूमेरिक वर्णों (वर्णमाला के सभी अक्षर, और अंक 0 से 9) और अंडरस्कोर (_) से बना होना चाहिए।

नाम का पहला वर्ण अक्षर होना चाहिए।

नाम केस-असंवेदनशील हैं।

पिछले अध्याय में बताए गए मूल प्रकारों के आधार पर, निम्नलिखित चर प्रकार हैं -

| अनु क्रमांक | टाइप और विवरण |

|---|---|

| 1 | Integer यह केवल पूर्णांक मानों को पकड़ सकता है। |

| 2 | Real यह फ्लोटिंग पॉइंट नंबरों को स्टोर करता है। |

| 3 | Complex इसका उपयोग जटिल संख्याओं के भंडारण के लिए किया जाता है। |

| 4 | Logical यह तार्किक बूलियन मूल्यों को संग्रहीत करता है। |

| 5 | Character यह पात्रों या तारों को संग्रहीत करता है। |

परिवर्तनीय घोषणा

एक प्रकार की घोषणा बयान में एक कार्यक्रम (या उपप्रोग्राम) की शुरुआत में चर घोषित किए जाते हैं।

परिवर्तनीय घोषणा के लिए सिंटैक्स निम्नानुसार है -

type-specifier :: variable_nameउदाहरण के लिए

integer :: total

real :: average

complex :: cx

logical :: done

character(len = 80) :: message ! a string of 80 charactersबाद में आप इन चरों के मान निर्दिष्ट कर सकते हैं, जैसे,

total = 20000

average = 1666.67

done = .true.

message = “A big Hello from Tutorials Point”

cx = (3.0, 5.0) ! cx = 3.0 + 5.0iआप आंतरिक फ़ंक्शन का उपयोग भी कर सकते हैं cmplx, एक जटिल चर के मूल्यों को आवंटित करने के लिए -

cx = cmplx (1.0/2.0, -7.0) ! cx = 0.5 – 7.0i

cx = cmplx (x, y) ! cx = x + yiउदाहरण

निम्न उदाहरण स्क्रीन पर चर घोषणा, असाइनमेंट और डिस्प्ले प्रदर्शित करता है -

program variableTesting

implicit none

! declaring variables

integer :: total

real :: average

complex :: cx

logical :: done

character(len=80) :: message ! a string of 80 characters

!assigning values

total = 20000

average = 1666.67

done = .true.

message = "A big Hello from Tutorials Point"

cx = (3.0, 5.0) ! cx = 3.0 + 5.0i

Print *, total

Print *, average

Print *, cx

Print *, done

Print *, message

end program variableTestingजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

20000

1666.67004

(3.00000000, 5.00000000 )

T

A big Hello from Tutorials Pointस्थिरांक उन निश्चित मानों को संदर्भित करता है जो कार्यक्रम इसके निष्पादन के दौरान बदल नहीं सकते हैं। इन निश्चित मूल्यों को भी कहा जाता हैliterals।

स्थिरांक किसी भी मूल डेटा प्रकार के हो सकते हैं जैसे पूर्णांक स्थिर, एक अस्थायी स्थिरांक, एक वर्ण स्थिरांक, एक जटिल स्थिरांक या एक स्ट्रिंग शाब्दिक। केवल दो तार्किक स्थिरांक हैं:.true. तथा .false.

स्थिरांक को नियमित चर की तरह माना जाता है, सिवाय इसके कि उनके मूल्यों को उनकी परिभाषा के बाद संशोधित नहीं किया जा सकता है।

जिसका नाम कांस्टेंट और लिटरेल्स रखा गया

दो प्रकार के स्थिरांक हैं -

- शाब्दिक अर्थ

- नाम दिया गया स्थिरांक

शाब्दिक स्थिरांक का एक मूल्य होता है, लेकिन कोई नाम नहीं।

उदाहरण के लिए, निम्नलिखित शाब्दिक स्थिरांक हैं -

| प्रकार | उदाहरण |

|---|---|

| पूर्णांक स्थिरांक | 0 1 -1 300 123456789 |

| वास्तविक स्थिरांक | 0.0 1.0 -1.0 123.456 7.1E + 10 -52.715E-30 |

| जटिल स्थिरांक | (0.0, 0.0) (-123.456E + 30, 987.654E-29) |

| तार्किक स्थिरांक | ।सच। ।असत्य। |

| चरित्र कांस्टेंट | "PQR" "a" "123'abc $% # @!" " एक बोली "" " 'PQR' 'a' '123 "abc $% # @!' 'एक धर्मोपदेश' '' |

एक नामित स्थिरांक का एक मान के साथ-साथ एक नाम भी होता है।

नामांकित स्थिरांक को एक कार्यक्रम या प्रक्रिया की शुरुआत में घोषित किया जाना चाहिए, एक चर प्रकार की घोषणा की तरह, इसके नाम और प्रकार को दर्शाता है। नामांकित स्थिरांक को पैरामीटर विशेषता के साथ घोषित किया जाता है। उदाहरण के लिए,

real, parameter :: pi = 3.1415927उदाहरण

निम्नलिखित कार्यक्रम गुरुत्वाकर्षण के तहत ऊर्ध्वाधर गति के कारण विस्थापन की गणना करता है।

program gravitationalDisp

! this program calculates vertical motion under gravity

implicit none

! gravitational acceleration

real, parameter :: g = 9.81

! variable declaration

real :: s ! displacement

real :: t ! time

real :: u ! initial speed

! assigning values

t = 5.0

u = 50

! displacement

s = u * t - g * (t**2) / 2

! output

print *, "Time = ", t

print *, 'Displacement = ',s

end program gravitationalDispजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

Time = 5.00000000

Displacement = 127.374992एक ऑपरेटर एक प्रतीक है जो संकलक को विशिष्ट गणितीय या तार्किक जोड़तोड़ करने के लिए कहता है। फोरट्रान निम्नलिखित प्रकार के ऑपरेटर प्रदान करता है -

- अंकगणितीय आपरेटर

- संबंधपरक संकारक

- लॉजिकल ऑपरेटर्स

आइए हम इन सभी प्रकार के ऑपरेटरों को एक-एक करके देखें।

अंकगणितीय आपरेटर

निम्नलिखित तालिका फ़ोर्ट्रान द्वारा समर्थित सभी अंकगणितीय ऑपरेटरों को दर्शाती है। चर मान लेंA 5 और चर रखता है B 3 तब रखता है -

उदाहरण दिखाएं

| ऑपरेटर | विवरण | उदाहरण |

|---|---|---|

| + | अतिरिक्त ऑपरेटर, दो ऑपरेंड जोड़ता है। | A + B 8 देगा |

| - | घटाव ऑपरेटर, पहले से दूसरे ऑपरेंड घटाता है। | A - B 2 देगा |

| * | गुणन ऑपरेटर, दोनों ऑपरेंड को गुणा करता है। | A * B 15 देगा |

| / | डिवीजन ऑपरेटर, अंश को डी-न्यूमेरियर द्वारा विभाजित करता है। | A / B 1 देगा |

| ** | एक्सपोनेशन ऑपरेटर, एक ऑपरेंड को दूसरे की शक्ति को बढ़ाता है। | A ** B 125 देगा |

संबंधपरक संकारक

निम्नलिखित तालिका में फोरट्रान द्वारा समर्थित सभी रिलेशनल ऑपरेटर्स को दिखाया गया है। चर मान लेंA 10 और चर रखता है B 20 रखती है, तो -

उदाहरण दिखाएं

| ऑपरेटर | समकक्ष | विवरण | उदाहरण |

|---|---|---|---|

| == | .eq। | जाँच करता है कि दो ऑपरेंड के मान समान हैं या नहीं, यदि हाँ तो स्थिति सच हो जाती है। | (ए == बी) सच नहीं है। |

| / = | .ne। | Checks if the values of two operands are equal or not, if values are not equal then condition becomes true. | (A != B) is true. |

| > | .gt. | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A > B) is not true. |

| < | .lt. | Checks if the value of left operand is less than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A < B) is true. |

| >= | .ge. | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A >= B) is not true. |

| <= | .le. | Checks if the value of left operand is less than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A <= B) is true. |

Logical Operators

Logical operators in Fortran work only on logical values .true. and .false.

The following table shows all the logical operators supported by Fortran. Assume variable A holds .true. and variable B holds .false. , then −

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| .and. | Called Logical AND operator. If both the operands are non-zero, then condition becomes true. | (A .and. B) is false. |

| .or. | Called Logical OR Operator. If any of the two operands is non-zero, then condition becomes true. | (A .or. B) is true. |

| .not. | Called Logical NOT Operator. Use to reverses the logical state of its operand. If a condition is true then Logical NOT operator will make false. | !(A .and. B) is true. |

| .eqv. | Called Logical EQUIVALENT Operator. Used to check equivalence of two logical values. | (A .eqv. B) is false. |

| .neqv. | Called Logical NON-EQUIVALENT Operator. Used to check non-equivalence of two logical values. | (A .neqv. B) is true. |

Operators Precedence in Fortran

Operator precedence determines the grouping of terms in an expression. This affects how an expression is evaluated. Certain operators have higher precedence than others; for example, the multiplication operator has higher precedence than the addition operator.

For example, x = 7 + 3 * 2; here, x is assigned 13, not 20 because operator * has higher precedence than +, so it first gets multiplied with 3*2 and then adds into 7.

Here, operators with the highest precedence appear at the top of the table, those with the lowest appear at the bottom. Within an expression, higher precedence operators will be evaluated first.

Show Examples

| Category | Operator | Associativity |

|---|---|---|

| Logical NOT and negative sign | .not. (-) | Left to right |

| Exponentiation | ** | Left to right |

| Multiplicative | * / | Left to right |

| Additive | + - | Left to right |

| Relational | < <= > >= | Left to right |

| Equality | == /= | Left to right |

| Logical AND | .and. | Left to right |

| Logical OR | .or. | Left to right |

| Assignment | = | Right to left |

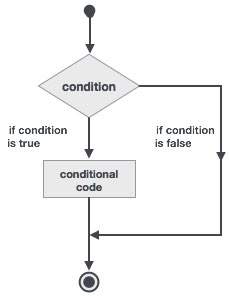

Decision making structures require that the programmer specify one or more conditions to be evaluated or tested by the program, along with a statement or statements to be executed, if the condition is determined to be true, and optionally, other statements to be executed if the condition is determined to be false.

Following is the general form of a typical decision making structure found in most of the programming languages −

Fortran provides the following types of decision making constructs.

| Sr.No | Statement & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | If… then construct An if… then… end if statement consists of a logical expression followed by one or more statements. |

| 2 | If… then...else construct An if… then statement can be followed by an optional else statement, which executes when the logical expression is false. |

| 3 | if...else if...else Statement An if statement construct can have one or more optional else-if constructs. When the if condition fails, the immediately followed else-if is executed. When the else-if also fails, its successor else-if statement (if any) is executed, and so on. |

| 4 | nested if construct You can use one if or else if statement inside another if or else if statement(s). |

| 5 | select case construct A select case statement allows a variable to be tested for equality against a list of values. |

| 6 | nested select case construct You can use one select case statement inside another select case statement(s). |

There may be a situation, when you need to execute a block of code several number of times. In general, statements are executed sequentially : The first statement in a function is executed first, followed by the second, and so on.

Programming languages provide various control structures that allow for more complicated execution paths.

A loop statement allows us to execute a statement or group of statements multiple times and following is the general form of a loop statement in most of the programming languages −

Fortran provides the following types of loop constructs to handle looping requirements. Click the following links to check their detail.

| Sr.No | Loop Type & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | do loop This construct enables a statement, or a series of statements, to be carried out iteratively, while a given condition is true. |

| 2 | do while loop Repeats a statement or group of statements while a given condition is true. It tests the condition before executing the loop body. |

| 3 | nested loops You can use one or more loop construct inside any other loop construct. |

Loop Control Statements

Loop control statements change execution from its normal sequence. When execution leaves a scope, all automatic objects that were created in that scope are destroyed.

Fortran supports the following control statements. Click the following links to check their detail.

| Sr.No | Control Statement & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | exit If the exit statement is executed, the loop is exited, and the execution of the program continues at the first executable statement after the end do statement. |

| 2 | cycle If a cycle statement is executed, the program continues at the start of the next iteration. |

| 3 | stop If you wish execution of your program to stop, you can insert a stop statement |

Numbers in Fortran are represented by three intrinsic data types −

- Integer type

- Real type

- Complex type

Integer Type

The integer types can hold only integer values. The following example extracts the largest value that could be hold in a usual four byte integer −

program testingInt

implicit none

integer :: largeval

print *, huge(largeval)

end program testingIntWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

2147483647Please note that the huge() function gives the largest number that can be held by the specific integer data type. You can also specify the number of bytes using the kind specifier. The following example demonstrates this −

program testingInt

implicit none

!two byte integer

integer(kind = 2) :: shortval

!four byte integer

integer(kind = 4) :: longval

!eight byte integer

integer(kind = 8) :: verylongval

!sixteen byte integer

integer(kind = 16) :: veryverylongval

!default integer

integer :: defval

print *, huge(shortval)

print *, huge(longval)

print *, huge(verylongval)

print *, huge(veryverylongval)

print *, huge(defval)

end program testingIntWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

32767

2147483647

9223372036854775807

170141183460469231731687303715884105727

2147483647Real Type

It stores the floating point numbers, such as 2.0, 3.1415, -100.876, etc.

Traditionally there were two different real types : the default real type and double precision type.

However, Fortran 90/95 provides more control over the precision of real and integer data types through the kind specifier, which we will study shortly.

The following example shows the use of real data type −

program division

implicit none

! Define real variables

real :: p, q, realRes

! Define integer variables

integer :: i, j, intRes

! Assigning values

p = 2.0

q = 3.0

i = 2

j = 3

! floating point division

realRes = p/q

intRes = i/j

print *, realRes

print *, intRes

end program divisionWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

0.666666687

0Complex Type

This is used for storing complex numbers. A complex number has two parts : the real part and the imaginary part. Two consecutive numeric storage units store these two parts.

For example, the complex number (3.0, -5.0) is equal to 3.0 – 5.0i

The generic function cmplx() creates a complex number. It produces a result who’s real and imaginary parts are single precision, irrespective of the type of the input arguments.

program createComplex

implicit none

integer :: i = 10

real :: x = 5.17

print *, cmplx(i, x)

end program createComplexWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

(10.0000000, 5.17000008)The following program demonstrates complex number arithmetic −

program ComplexArithmatic

implicit none

complex, parameter :: i = (0, 1) ! sqrt(-1)

complex :: x, y, z

x = (7, 8);

y = (5, -7)

write(*,*) i * x * y

z = x + y

print *, "z = x + y = ", z

z = x - y

print *, "z = x - y = ", z

z = x * y

print *, "z = x * y = ", z

z = x / y

print *, "z = x / y = ", z

end program ComplexArithmaticWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

(9.00000000, 91.0000000)

z = x + y = (12.0000000, 1.00000000)

z = x - y = (2.00000000, 15.0000000)

z = x * y = (91.0000000, -9.00000000)

z = x / y = (-0.283783793, 1.20270276)The Range, Precision and Size of Numbers

The range on integer numbers, the precision and the size of floating point numbers depends on the number of bits allocated to the specific data type.

The following table displays the number of bits and range for integers −

| Number of bits | Maximum value | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| 64 | 9,223,372,036,854,774,807 | (2**63)–1 |

| 32 | 2,147,483,647 | (2**31)–1 |

The following table displays the number of bits, smallest and largest value, and the precision for real numbers.

| Number of bits | Largest value | Smallest value | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 0.8E+308 | 0.5E–308 | 15–18 |

| 32 | 1.7E+38 | 0.3E–38 | 6-9 |

The following examples demonstrate this −

program rangePrecision

implicit none

real:: x, y, z

x = 1.5e+40

y = 3.73e+40

z = x * y

print *, z

end program rangePrecisionWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

x = 1.5e+40

1

Error : Real constant overflows its kind at (1)

main.f95:5.12:

y = 3.73e+40

1

Error : Real constant overflows its kind at (1)Now let us use a smaller number −

program rangePrecision

implicit none

real:: x, y, z

x = 1.5e+20

y = 3.73e+20

z = x * y

print *, z

z = x/y

print *, z

end program rangePrecisionWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Infinity

0.402144760Now let’s watch underflow −

program rangePrecision

implicit none

real:: x, y, z

x = 1.5e-30

y = 3.73e-60

z = x * y

print *, z

z = x/y

print *, z

end program rangePrecisionWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

y = 3.73e-60

1

Warning : Real constant underflows its kind at (1)

Executing the program....

$demo

0.00000000E+00

InfinityThe Kind Specifier

In scientific programming, one often needs to know the range and precision of data of the hardware platform on which the work is being done.

The intrinsic function kind() allows you to query the details of the hardware’s data representations before running a program.

program kindCheck

implicit none

integer :: i

real :: r

complex :: cp

print *,' Integer ', kind(i)

print *,' Real ', kind(r)

print *,' Complex ', kind(cp)

end program kindCheckWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Integer 4

Real 4

Complex 4You can also check the kind of all data types −

program checkKind

implicit none

integer :: i

real :: r

character :: c

logical :: lg

complex :: cp

print *,' Integer ', kind(i)

print *,' Real ', kind(r)

print *,' Complex ', kind(cp)

print *,' Character ', kind(c)

print *,' Logical ', kind(lg)

end program checkKindWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Integer 4

Real 4

Complex 4

Character 1

Logical 4The Fortran language can treat characters as single character or contiguous strings.

Characters could be any symbol taken from the basic character set, i.e., from the letters, the decimal digits, the underscore, and 21 special characters.

A character constant is a fixed valued character string.

The intrinsic data type character stores characters and strings. The length of the string can be specified by len specifier. If no length is specified, it is 1. You can refer individual characters within a string referring by position; the left most character is at position 1.

Character Declaration

Declaring a character type data is same as other variables −

type-specifier :: variable_nameFor example,

character :: reply, sexyou can assign a value like,

reply = ‘N’

sex = ‘F’The following example demonstrates declaration and use of character data type −

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 25)::greetings

title = 'Mr. '

firstname = 'Rowan '

surname = 'Atkinson'

greetings = 'A big hello from Mr. Bean'

print *, 'Here is ', title, firstname, surname

print *, greetings

end program helloWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Here is Mr. Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr. BeanConcatenation of Characters

The concatenation operator //, concatenates characters.

The following example demonstrates this −

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 40):: name

character(len = 25)::greetings

title = 'Mr. '

firstname = 'Rowan '

surname = 'Atkinson'

name = title//firstname//surname

greetings = 'A big hello from Mr. Bean'

print *, 'Here is ', name

print *, greetings

end program helloWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Here is Mr.Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr.BeanSome Character Functions

The following table shows some commonly used character functions along with the description −

| Sr.No | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | len(string) It returns the length of a character string |

| 2 | index(string,sustring) It finds the location of a substring in another string, returns 0 if not found. |

| 3 | achar(int) It converts an integer into a character |

| 4 | iachar(c) It converts a character into an integer |

| 5 | trim(string) It returns the string with the trailing blanks removed. |

| 6 | scan(string, chars) It searches the "string" from left to right (unless back=.true.) for the first occurrence of any character contained in "chars". It returns an integer giving the position of that character, or zero if none of the characters in "chars" have been found. |

| 7 | verify(string, chars) It scans the "string" from left to right (unless back=.true.) for the first occurrence of any character not contained in "chars". It returns an integer giving the position of that character, or zero if only the characters in "chars" have been found |

| 8 | adjustl(string) It left justifies characters contained in the "string" |

| 9 | adjustr(string) It right justifies characters contained in the "string" |

| 10 | len_trim(string) It returns an integer equal to the length of "string" (len(string)) minus the number of trailing blanks |

| 11 | repeat(string,ncopy) It returns a string with length equal to "ncopy" times the length of "string", and containing "ncopy" concatenated copies of "string" |

Example 1

This example shows the use of the index function −

program testingChars

implicit none

character (80) :: text

integer :: i

text = 'The intrinsic data type character stores characters and strings.'

i=index(text,'character')

if (i /= 0) then

print *, ' The word character found at position ',i

print *, ' in text: ', text

end if

end program testingCharsWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

The word character found at position 25

in text : The intrinsic data type character stores characters and strings.Example 2

This example demonstrates the use of the trim function −

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 25)::greetings

title = 'Mr.'

firstname = 'Rowan'

surname = 'Atkinson'

print *, 'Here is', title, firstname, surname

print *, 'Here is', trim(title),' ',trim(firstname),' ', trim(surname)

end program helloWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Here isMr. Rowan Atkinson

Here isMr. Rowan AtkinsonExample 3

This example demonstrates the use of achar function −

program testingChars

implicit none

character:: ch

integer:: i

do i = 65, 90

ch = achar(i)

print*, i, ' ', ch

end do

end program testingCharsWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

65 A

66 B

67 C

68 D

69 E

70 F

71 G

72 H

73 I

74 J

75 K

76 L

77 M

78 N

79 O

80 P

81 Q

82 R

83 S

84 T

85 U

86 V

87 W

88 X

89 Y

90 ZChecking Lexical Order of Characters

The following functions determine the lexical sequence of characters −

| Sr.No | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | lle(char, char) Compares whether the first character is lexically less than or equal to the second |

| 2 | lge(char, char) Compares whether the first character is lexically greater than or equal to the second |

| 3 | lgt(char, char) Compares whether the first character is lexically greater than the second |

| 4 | llt(char, char) Compares whether the first character is lexically less than the second |

Example 4

The following function demonstrates the use −

program testingChars

implicit none

character:: a, b, c

a = 'A'

b = 'a'

c = 'B'

if(lgt(a,b)) then

print *, 'A is lexically greater than a'

else

print *, 'a is lexically greater than A'

end if

if(lgt(a,c)) then

print *, 'A is lexically greater than B'

else

print *, 'B is lexically greater than A'

end if

if(llt(a,b)) then

print *, 'A is lexically less than a'

end if

if(llt(a,c)) then

print *, 'A is lexically less than B'

end if

end program testingCharsWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

a is lexically greater than A

B is lexically greater than A

A is lexically less than a

A is lexically less than BThe Fortran language can treat characters as single character or contiguous strings.

A character string may be only one character in length, or it could even be of zero length. In Fortran, character constants are given between a pair of double or single quotes.

The intrinsic data type character stores characters and strings. The length of the string can be specified by len specifier. If no length is specified, it is 1. You can refer individual characters within a string referring by position; the left most character is at position 1.

String Declaration

Declaring a string is same as other variables −

type-specifier :: variable_nameFor example,

Character(len = 20) :: firstname, surnameyou can assign a value like,

character (len = 40) :: name

name = “Zara Ali”The following example demonstrates declaration and use of character data type −

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 25)::greetings

title = 'Mr.'

firstname = 'Rowan'

surname = 'Atkinson'

greetings = 'A big hello from Mr. Beans'

print *, 'Here is', title, firstname, surname

print *, greetings

end program helloWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Here isMr. Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr. BeanString Concatenation

The concatenation operator //, concatenates strings.

The following example demonstrates this −

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 40):: name

character(len = 25)::greetings

title = 'Mr.'

firstname = 'Rowan'

surname = 'Atkinson'

name = title//firstname//surname

greetings = 'A big hello from Mr. Beans'

print *, 'Here is', name

print *, greetings

end program helloWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Here is Mr. Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr. BeanExtracting Substrings

In Fortran, you can extract a substring from a string by indexing the string, giving the start and the end index of the substring in a pair of brackets. This is called extent specifier.

The following example shows how to extract the substring ‘world’ from the string ‘hello world’ −

program subString

character(len = 11)::hello

hello = "Hello World"

print*, hello(7:11)

end program subStringWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

WorldExample

The following example uses the date_and_time function to give the date and time string. We use extent specifiers to extract the year, date, month, hour, minutes and second information separately.

program datetime

implicit none

character(len = 8) :: dateinfo ! ccyymmdd

character(len = 4) :: year, month*2, day*2

character(len = 10) :: timeinfo ! hhmmss.sss

character(len = 2) :: hour, minute, second*6

call date_and_time(dateinfo, timeinfo)

! let’s break dateinfo into year, month and day.

! dateinfo has a form of ccyymmdd, where cc = century, yy = year

! mm = month and dd = day

year = dateinfo(1:4)

month = dateinfo(5:6)

day = dateinfo(7:8)

print*, 'Date String:', dateinfo

print*, 'Year:', year

print *,'Month:', month

print *,'Day:', day

! let’s break timeinfo into hour, minute and second.

! timeinfo has a form of hhmmss.sss, where h = hour, m = minute

! and s = second

hour = timeinfo(1:2)

minute = timeinfo(3:4)

second = timeinfo(5:10)

print*, 'Time String:', timeinfo

print*, 'Hour:', hour

print*, 'Minute:', minute

print*, 'Second:', second

end program datetimeWhen you compile and execute the above program, it gives the detailed date and time information −

Date String: 20140803

Year: 2014

Month: 08

Day: 03

Time String: 075835.466

Hour: 07

Minute: 58

Second: 35.466Trimming Strings

The trim function takes a string, and returns the input string after removing all trailing blanks.

Example

program trimString

implicit none

character (len = *), parameter :: fname="Susanne", sname="Rizwan"

character (len = 20) :: fullname

fullname = fname//" "//sname !concatenating the strings

print*,fullname,", the beautiful dancer from the east!"

print*,trim(fullname),", the beautiful dancer from the east!"

end program trimStringWhen you compile and execute the above program it produces the following result −

Susanne Rizwan , the beautiful dancer from the east!

Susanne Rizwan, the beautiful dancer from the east!Left and Right Adjustment of Strings

The function adjustl takes a string and returns it by removing the leading blanks and appending them as trailing blanks.

The function adjustr takes a string and returns it by removing the trailing blanks and appending them as leading blanks.

Example

program hello

implicit none

character(len = 15) :: surname, firstname

character(len = 6) :: title

character(len = 40):: name

character(len = 25):: greetings

title = 'Mr. '

firstname = 'Rowan'

surname = 'Atkinson'

greetings = 'A big hello from Mr. Beans'

name = adjustl(title)//adjustl(firstname)//adjustl(surname)

print *, 'Here is', name

print *, greetings

name = adjustr(title)//adjustr(firstname)//adjustr(surname)

print *, 'Here is', name

print *, greetings

name = trim(title)//trim(firstname)//trim(surname)

print *, 'Here is', name

print *, greetings

end program helloजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

Here is Mr. Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr. Bean

Here is Mr. Rowan Atkinson

A big hello from Mr. Bean

Here is Mr.RowanAtkinson

A big hello from Mr. Beanएक स्ट्रिंग में एक विकल्प के लिए खोज

इंडेक्स फ़ंक्शन दो स्ट्रिंग्स लेता है और जांचता है कि क्या दूसरा स्ट्रिंग पहले स्ट्रिंग का एक विकल्प है। यदि दूसरा तर्क पहले तर्क का एक विकल्प है, तो यह एक पूर्णांक लौटाता है जो पहले स्ट्रिंग में दूसरे स्ट्रिंग का शुरुआती सूचकांक है, अन्यथा यह शून्य देता है।

उदाहरण

program hello

implicit none

character(len=30) :: myString

character(len=10) :: testString

myString = 'This is a test'

testString = 'test'

if(index(myString, testString) == 0)then

print *, 'test is not found'

else

print *, 'test is found at index: ', index(myString, testString)

end if

end program helloजब आप उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम को संकलित और निष्पादित करते हैं तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

test is found at index: 11Arrays एक ही प्रकार के तत्वों के एक निश्चित आकार के अनुक्रमिक संग्रह को संग्रहीत कर सकता है। एक सरणी का उपयोग डेटा के संग्रह को संग्रहीत करने के लिए किया जाता है, लेकिन एक सरणी के एक ही प्रकार के संग्रह के रूप में सरणी के बारे में सोचना अक्सर अधिक उपयोगी होता है।

सभी सरणियों में सन्निहित स्मृति स्थान शामिल हैं। निम्नतम पता पहले तत्व से मेल खाता है और उच्चतम पता अंतिम तत्व से।

| नंबर (1) | नंबर (2) | नंबर (3) | नंबर (4) | ... |

Arrays एक आयामी (वैक्टर की तरह) हो सकता है, द्वि-आयामी (जैसे matrices) और फोरट्रान आपको 7-आयामी सरणियों को बनाने की अनुमति देता है।

घोषणाएँ

ऐरे के साथ घोषित किया जाता है dimension विशेषता।

उदाहरण के लिए, 5 तत्वों से युक्त वास्तविक संख्याओं में से एक एक आयामी सारणी घोषित करने के लिए, आप लिखते हैं,

real, dimension(5) :: numbersसरणियों के व्यक्तिगत तत्वों को उनके ग्राहकों को निर्दिष्ट करके संदर्भित किया जाता है। किसी सरणी के पहले तत्व में एक का एक सबस्क्रिप्ट है। सरणी संख्याओं में पाँच वास्तविक चर-अंक (1), संख्याएँ (2), संख्याएँ (3), संख्याएँ (4) और संख्याएँ (5) शामिल हैं।

मैट्रिक्स नामक पूर्णांक के 5 x 5 द्वि-आयामी सरणी बनाने के लिए, आप लिखते हैं -

integer, dimension (5,5) :: matrixआप कुछ स्पष्ट निचली सीमाओं के साथ एक सरणी भी घोषित कर सकते हैं, उदाहरण के लिए -

real, dimension(2:6) :: numbers

integer, dimension (-3:2,0:4) :: matrixमान देना

आप या तो व्यक्तिगत सदस्यों को मान असाइन कर सकते हैं, जैसे,

numbers(1) = 2.0या, आप एक लूप का उपयोग कर सकते हैं,

do i =1,5

numbers(i) = i * 2.0

end doएक आयामी सरणी तत्वों को शॉर्ट हैंड सिंबल का उपयोग करके सीधे मान दिए जा सकते हैं, जिन्हें एरे कंस्ट्रक्टर कहा जाता है, जैसे

numbers = (/1.5, 3.2,4.5,0.9,7.2 /)please note that there are no spaces allowed between the brackets ‘( ‘and the back slash ‘/’

उदाहरण

निम्न उदाहरण ऊपर चर्चा की गई अवधारणाओं को प्रदर्शित करता है।

program arrayProg

real :: numbers(5) !one dimensional integer array

integer :: matrix(3,3), i , j !two dimensional real array

!assigning some values to the array numbers

do i=1,5

numbers(i) = i * 2.0

end do

!display the values

do i = 1, 5

Print *, numbers(i)

end do

!assigning some values to the array matrix

do i=1,3

do j = 1, 3

matrix(i, j) = i+j

end do

end do

!display the values

do i=1,3

do j = 1, 3

Print *, matrix(i,j)

end do

end do

!short hand assignment

numbers = (/1.5, 3.2,4.5,0.9,7.2 /)

!display the values

do i = 1, 5

Print *, numbers(i)

end do

end program arrayProgजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

2.00000000

4.00000000

6.00000000

8.00000000

10.0000000

2

3

4

3

4

5

4

5

6

1.50000000

3.20000005

4.50000000

0.899999976

7.19999981कुछ ऐरे संबंधित शर्तें

निम्न तालिका कुछ सरणी से संबंधित शब्द देती है -

| अवधि | जिसका अर्थ है |

|---|---|

| पद | यह एक सरणी के आयामों की संख्या है। उदाहरण के लिए, मैट्रिक्स नामक सरणी के लिए, रैंक 2 है, और संख्याओं के नाम वाले सरणी के लिए, रैंक 1 है। |

| सीमा | यह एक आयाम के साथ तत्वों की संख्या है। उदाहरण के लिए, सरणी संख्याओं की सीमा 5 है और मैट्रिक्स नाम के सरणी की दोनों आयामों में सीमा 3 है। |

| आकार | एक सरणी का आकार एक आयामी पूर्णांक सरणी है, जिसमें प्रत्येक आयाम में तत्वों की संख्या (सीमा) होती है। उदाहरण के लिए, सरणी मैट्रिक्स के लिए, आकार (3, 3) है और सरणी संख्या यह (5) है। |

| आकार | यह उन तत्वों की संख्या है जिनमें एक सरणी होती है। सरणी मैट्रिक्स के लिए, यह 9 है, और सरणी संख्याओं के लिए, यह 5 है। |

प्रक्रियाओं को पास करना

आप एक सरणी को एक तर्क के रूप में एक प्रक्रिया में पास कर सकते हैं। निम्नलिखित उदाहरण अवधारणा को प्रदर्शित करता है -

program arrayToProcedure

implicit none

integer, dimension (5) :: myArray

integer :: i

call fillArray (myArray)

call printArray(myArray)

end program arrayToProcedure

subroutine fillArray (a)

implicit none

integer, dimension (5), intent (out) :: a

! local variables

integer :: i

do i = 1, 5

a(i) = i

end do

end subroutine fillArray

subroutine printArray(a)

integer, dimension (5) :: a

integer::i

do i = 1, 5

Print *, a(i)

end do

end subroutine printArrayजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

1

2

3

4

5उपरोक्त उदाहरण में, सबरूटीन फिलअरे और प्रिंटअरे को केवल आयाम 5 के साथ सरणियों के साथ कहा जा सकता है। हालांकि, सबरूटीन्स को लिखने के लिए जो किसी भी आकार के सरणियों के लिए इस्तेमाल किया जा सकता है, आप इसे निम्नलिखित तकनीक का उपयोग करके फिर से लिख सकते हैं -

program arrayToProcedure

implicit none

integer, dimension (10) :: myArray

integer :: i

interface

subroutine fillArray (a)

integer, dimension(:), intent (out) :: a

integer :: i

end subroutine fillArray

subroutine printArray (a)

integer, dimension(:) :: a

integer :: i

end subroutine printArray

end interface

call fillArray (myArray)

call printArray(myArray)

end program arrayToProcedure

subroutine fillArray (a)

implicit none

integer,dimension (:), intent (out) :: a

! local variables

integer :: i, arraySize

arraySize = size(a)

do i = 1, arraySize

a(i) = i

end do

end subroutine fillArray

subroutine printArray(a)

implicit none

integer,dimension (:) :: a

integer::i, arraySize

arraySize = size(a)

do i = 1, arraySize

Print *, a(i)

end do

end subroutine printArrayकृपया ध्यान दें कि कार्यक्रम का उपयोग कर रहा है size सरणी का आकार प्राप्त करने के लिए कार्य करते हैं।

जब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10सरणी अनुभाग

अब तक हमने पूरे ऐरे को संदर्भित किया है, फ़ोर्ट्रान एक कथन का उपयोग करके, कई तत्वों या किसी ऐरे के एक सेक्शन को संदर्भित करने का एक आसान तरीका प्रदान करता है।

एक सरणी अनुभाग तक पहुंचने के लिए, आपको सभी आयामों के लिए अनुभाग के निचले और ऊपरी हिस्से, साथ ही एक स्ट्राइड (वेतन वृद्धि) प्रदान करने की आवश्यकता है। इस संकेतन को a कहा जाता हैsubscript triplet:

array ([lower]:[upper][:stride], ...)जब कोई निचली और ऊपरी सीमा का उल्लेख नहीं किया जाता है, तो यह आपके द्वारा घोषित किए गए अंशों को डिफॉल्ट करता है, और वैल्यू डिफॉल्ट को 1 पर ले जाता है।

निम्नलिखित उदाहरण अवधारणा को प्रदर्शित करता है -

program arraySubsection

real, dimension(10) :: a, b

integer:: i, asize, bsize

a(1:7) = 5.0 ! a(1) to a(7) assigned 5.0

a(8:) = 0.0 ! rest are 0.0

b(2:10:2) = 3.9

b(1:9:2) = 2.5

!display

asize = size(a)

bsize = size(b)

do i = 1, asize

Print *, a(i)

end do

do i = 1, bsize

Print *, b(i)

end do

end program arraySubsectionजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

5.00000000

5.00000000

5.00000000

5.00000000

5.00000000

5.00000000

5.00000000

0.00000000E+00

0.00000000E+00

0.00000000E+00

2.50000000

3.90000010

2.50000000

3.90000010

2.50000000

3.90000010

2.50000000

3.90000010

2.50000000

3.90000010आंतरिक आंतरिक कार्य

फोरट्रान 90/95 कई आंतरिक प्रक्रियाएं प्रदान करता है। उन्हें 7 श्रेणियों में विभाजित किया जा सकता है।

वेक्टर और मैट्रिक्स गुणन

Reduction

Inquiry

Construction

Reshape

Manipulation

Location

ए dynamic array एक सरणी है, जिसका आकार संकलन समय पर ज्ञात नहीं है, लेकिन निष्पादन समय पर जाना जाएगा।

गतिशील सरणियों को विशेषता के साथ घोषित किया जाता है allocatable।

उदाहरण के लिए,

real, dimension (:,:), allocatable :: darrayसरणी की रैंक, यानी, आयामों का उल्लेख किया जाना चाहिए, लेकिन इस तरह के एक सरणी को मेमोरी आवंटित करने के लिए, आप इसका उपयोग करते हैं allocate समारोह।

allocate ( darray(s1,s2) )सरणी का उपयोग करने के बाद, प्रोग्राम में, बनाई गई मेमोरी को उपयोग करके मुक्त किया जाना चाहिए deallocate समारोह

deallocate (darray)उदाहरण

निम्न उदाहरण ऊपर चर्चा की गई अवधारणाओं को प्रदर्शित करता है।

program dynamic_array

implicit none

!rank is 2, but size not known

real, dimension (:,:), allocatable :: darray

integer :: s1, s2

integer :: i, j

print*, "Enter the size of the array:"

read*, s1, s2

! allocate memory

allocate ( darray(s1,s2) )

do i = 1, s1

do j = 1, s2

darray(i,j) = i*j

print*, "darray(",i,",",j,") = ", darray(i,j)

end do

end do

deallocate (darray)

end program dynamic_arrayजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

Enter the size of the array: 3,4

darray( 1 , 1 ) = 1.00000000

darray( 1 , 2 ) = 2.00000000

darray( 1 , 3 ) = 3.00000000

darray( 1 , 4 ) = 4.00000000

darray( 2 , 1 ) = 2.00000000

darray( 2 , 2 ) = 4.00000000

darray( 2 , 3 ) = 6.00000000

darray( 2 , 4 ) = 8.00000000

darray( 3 , 1 ) = 3.00000000

darray( 3 , 2 ) = 6.00000000

darray( 3 , 3 ) = 9.00000000

darray( 3 , 4 ) = 12.0000000डेटा स्टेटमेंट का उपयोग

data स्टेटमेंट को एक से अधिक एरे को इनिशियलाइज़ करने के लिए या ऐरे सेक्शन आरंभीकरण के लिए इस्तेमाल किया जा सकता है।

डेटा स्टेटमेंट का सिंटैक्स है -

data variable / list / ...उदाहरण

निम्नलिखित उदाहरण अवधारणा को प्रदर्शित करता है -

program dataStatement

implicit none

integer :: a(5), b(3,3), c(10),i, j

data a /7,8,9,10,11/

data b(1,:) /1,1,1/

data b(2,:)/2,2,2/

data b(3,:)/3,3,3/

data (c(i),i = 1,10,2) /4,5,6,7,8/

data (c(i),i = 2,10,2)/5*2/

Print *, 'The A array:'

do j = 1, 5

print*, a(j)

end do

Print *, 'The B array:'

do i = lbound(b,1), ubound(b,1)

write(*,*) (b(i,j), j = lbound(b,2), ubound(b,2))

end do

Print *, 'The C array:'

do j = 1, 10

print*, c(j)

end do

end program dataStatementजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

The A array:

7

8

9

10

11

The B array:

1 1 1

2 2 2

3 3 3

The C array:

4

2

5

2

6

2

7

2

8

2कहां का उपयोग वक्तव्य

whereकथन आपको कुछ तार्किक स्थिति के परिणाम के आधार पर एक अभिव्यक्ति में सरणी के कुछ तत्वों का उपयोग करने की अनुमति देता है। यह किसी तत्व पर अभिव्यक्ति के निष्पादन की अनुमति देता है, यदि दी गई स्थिति सत्य है।

उदाहरण

निम्नलिखित उदाहरण अवधारणा को प्रदर्शित करता है -

program whereStatement

implicit none

integer :: a(3,5), i , j

do i = 1,3

do j = 1, 5

a(i,j) = j-i

end do

end do

Print *, 'The A array:'

do i = lbound(a,1), ubound(a,1)

write(*,*) (a(i,j), j = lbound(a,2), ubound(a,2))

end do

where( a<0 )

a = 1

elsewhere

a = 5

end where

Print *, 'The A array:'

do i = lbound(a,1), ubound(a,1)

write(*,*) (a(i,j), j = lbound(a,2), ubound(a,2))

end do

end program whereStatementजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

The A array:

0 1 2 3 4

-1 0 1 2 3

-2 -1 0 1 2

The A array:

5 5 5 5 5

1 5 5 5 5

1 1 5 5 5फोरट्रान आपको व्युत्पन्न डेटा प्रकारों को परिभाषित करने की अनुमति देता है। एक व्युत्पन्न डेटा प्रकार को एक संरचना भी कहा जाता है, और इसमें विभिन्न प्रकार के डेटा ऑब्जेक्ट शामिल हो सकते हैं।

एक रिकॉर्ड का प्रतिनिधित्व करने के लिए व्युत्पन्न डेटा प्रकार का उपयोग किया जाता है। उदाहरण के लिए, आप अपनी पुस्तकों पर एक पुस्तकालय में नज़र रखना चाहते हैं, आप प्रत्येक पुस्तक के बारे में निम्नलिखित विशेषताओं को ट्रैक करना चाहते हैं -

- Title

- Author

- Subject

- बुक आईडी

एक व्युत्पन्न डेटा प्रकार को परिभाषित करना

एक व्युत्पन्न डेटा को परिभाषित करने के लिए type, प्रकार और end typeबयानों का उपयोग किया जाता है। । टाइप स्टेटमेंट एक नए डेटा प्रकार को परिभाषित करता है, जिसमें आपके प्रोग्राम के लिए एक से अधिक सदस्य होते हैं। टाइप स्टेटमेंट का प्रारूप यह है -

type type_name

declarations

end typeयहाँ आप बुक संरचना को घोषित करने का तरीका है -

type Books

character(len = 50) :: title

character(len = 50) :: author

character(len = 150) :: subject

integer :: book_id

end type Booksसंरचना सदस्यों तक पहुँचना

एक व्युत्पन्न डेटा प्रकार के ऑब्जेक्ट को एक संरचना कहा जाता है।

एक प्रकार की पुस्तकों की संरचना एक प्रकार की घोषणा के बयान में बनाई जा सकती है जैसे -

type(Books) :: book1संरचना के घटक घटक चयनकर्ता चरित्र (%) का उपयोग करके पहुँचा जा सकता है -

book1%title = "C Programming"

book1%author = "Nuha Ali"

book1%subject = "C Programming Tutorial"

book1%book_id = 6495407Note that there are no spaces before and after the % symbol.

उदाहरण

निम्नलिखित कार्यक्रम उपरोक्त अवधारणाओं को दर्शाता है -

program deriveDataType

!type declaration

type Books

character(len = 50) :: title

character(len = 50) :: author

character(len = 150) :: subject

integer :: book_id

end type Books

!declaring type variables

type(Books) :: book1

type(Books) :: book2

!accessing the components of the structure

book1%title = "C Programming"

book1%author = "Nuha Ali"

book1%subject = "C Programming Tutorial"

book1%book_id = 6495407

book2%title = "Telecom Billing"

book2%author = "Zara Ali"

book2%subject = "Telecom Billing Tutorial"

book2%book_id = 6495700

!display book info

Print *, book1%title

Print *, book1%author

Print *, book1%subject

Print *, book1%book_id

Print *, book2%title

Print *, book2%author

Print *, book2%subject

Print *, book2%book_id

end program deriveDataTypeजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

C Programming

Nuha Ali

C Programming Tutorial

6495407

Telecom Billing

Zara Ali

Telecom Billing Tutorial

6495700संरचनाओं की सरणी

आप एक व्युत्पन्न प्रकार के सरणियाँ भी बना सकते हैं -

type(Books), dimension(2) :: listसरणी के अलग-अलग तत्वों को इस प्रकार एक्सेस किया जा सकता है -

list(1)%title = "C Programming"

list(1)%author = "Nuha Ali"

list(1)%subject = "C Programming Tutorial"

list(1)%book_id = 6495407निम्नलिखित कार्यक्रम अवधारणा को दर्शाता है -

program deriveDataType

!type declaration

type Books

character(len = 50) :: title

character(len = 50) :: author

character(len = 150) :: subject

integer :: book_id

end type Books

!declaring array of books

type(Books), dimension(2) :: list

!accessing the components of the structure

list(1)%title = "C Programming"

list(1)%author = "Nuha Ali"

list(1)%subject = "C Programming Tutorial"

list(1)%book_id = 6495407

list(2)%title = "Telecom Billing"

list(2)%author = "Zara Ali"

list(2)%subject = "Telecom Billing Tutorial"

list(2)%book_id = 6495700

!display book info

Print *, list(1)%title

Print *, list(1)%author

Print *, list(1)%subject

Print *, list(1)%book_id

Print *, list(1)%title

Print *, list(2)%author

Print *, list(2)%subject

Print *, list(2)%book_id

end program deriveDataTypeजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

C Programming

Nuha Ali

C Programming Tutorial

6495407

C Programming

Zara Ali

Telecom Billing Tutorial

6495700अधिकांश प्रोग्रामिंग भाषाओं में, एक पॉइंटर वेरिएबल किसी ऑब्जेक्ट की मेमोरी एड्रेस को स्टोर करता है। हालांकि, फोरट्रान में, एक सूचक एक डेटा ऑब्जेक्ट है जिसमें मेमोरी एड्रेस को स्टोर करने की तुलना में अधिक कार्यक्षमताओं हैं। इसमें किसी विशेष वस्तु के बारे में अधिक जानकारी होती है, जैसे प्रकार, रैंक, विस्तार और स्मृति पता।

एक संकेतक आवंटन या पॉइंटर असाइनमेंट द्वारा एक लक्ष्य के साथ जुड़ा हुआ है।

एक सूचक चर की घोषणा

पॉइंटर चर को पॉइंटर विशेषता के साथ घोषित किया जाता है।

निम्न उदाहरण सूचक चर की घोषणा को दर्शाता है -

integer, pointer :: p1 ! pointer to integer

real, pointer, dimension (:) :: pra ! pointer to 1-dim real array

real, pointer, dimension (:,:) :: pra2 ! pointer to 2-dim real arrayएक सूचक को इंगित कर सकते हैं -

गतिशील रूप से आवंटित स्मृति का एक क्षेत्र।

सूचक के साथ एक ही प्रकार का डेटा ऑब्जेक्ट target विशेषता।

एक सूचक के लिए आवंटित स्थान

allocateस्टेटमेंट आपको पॉइंटर ऑब्जेक्ट के लिए जगह आवंटित करने की अनुमति देता है। उदाहरण के लिए -

program pointerExample

implicit none

integer, pointer :: p1

allocate(p1)

p1 = 1

Print *, p1

p1 = p1 + 4

Print *, p1

end program pointerExampleजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

1

5आपको आवंटित भंडारण स्थान को खाली करना चाहिए deallocate बयान जब यह आवश्यक नहीं है और अप्रयुक्त और अनुपयोगी स्मृति स्थान के संचय से बचें।

लक्ष्य और एसोसिएशन

एक लक्ष्य एक और सामान्य चर है, इसके लिए अलग स्थान निर्धारित किया गया है। के साथ एक लक्ष्य चर घोषित किया जाना चाहिएtarget विशेषता।

आप संघ संचालक (=>) का उपयोग करके एक सूचक चर को लक्ष्य चर के साथ जोड़ते हैं।

आइए हम पिछले उदाहरण को फिर से लिखें, अवधारणा को प्रदर्शित करने के लिए -

program pointerExample

implicit none

integer, pointer :: p1

integer, target :: t1

p1=>t1

p1 = 1

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

p1 = p1 + 4

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

t1 = 8

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

end program pointerExampleजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

1

1

5

5

8

8एक सूचक हो सकता है -

- Undefined

- Associated

- Disassociated

उपरोक्त कार्यक्रम में, हमारे पास है associatedसूचक p1, लक्ष्य t1 के साथ, => ऑपरेटर का उपयोग कर। फ़ंक्शन जुड़ा हुआ है, एक पॉइंटर एसोसिएशन की स्थिति का परीक्षण करता है।

nullify बयान एक लक्ष्य से एक सूचक को अलग कर देता है।

Nullify लक्ष्य को खाली नहीं करता है क्योंकि एक ही लक्ष्य को इंगित करने वाले एक से अधिक पॉइंटर हो सकते हैं। हालाँकि, पॉइंटर को खाली करने से तात्पर्य अशक्तता भी है।

उदाहरण 1

निम्नलिखित उदाहरण अवधारणाओं को प्रदर्शित करता है -

program pointerExample

implicit none

integer, pointer :: p1

integer, target :: t1

integer, target :: t2

p1=>t1

p1 = 1

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

p1 = p1 + 4

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

t1 = 8

Print *, p1

Print *, t1

nullify(p1)

Print *, t1

p1=>t2

Print *, associated(p1)

Print*, associated(p1, t1)

Print*, associated(p1, t2)

!what is the value of p1 at present

Print *, p1

Print *, t2

p1 = 10

Print *, p1

Print *, t2

end program pointerExampleजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

1

1

5

5

8

8

8

T

F

T

952754640

952754640

10

10कृपया ध्यान दें कि हर बार जब आप कोड चलाते हैं, तो मेमोरी पते अलग-अलग होंगे।

उदाहरण 2

program pointerExample

implicit none

integer, pointer :: a, b

integer, target :: t

integer :: n

t = 1

a => t

t = 2

b => t

n = a + b

Print *, a, b, t, n

end program pointerExampleजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

2 2 2 4हमने अब तक देखा है कि हम कीबोर्ड के डेटा का उपयोग करके पढ़ सकते हैं read * स्टेटमेंट, और डिस्प्ले आउटपुट को स्क्रीन का उपयोग करके print*बयान, क्रमशः। इनपुट-आउटपुट का यह रूप हैfree format I / O, और इसे कहा जाता है list-directed इनपुट आउटपुट।

सरल प्रारूप I / O का प्रारूप है -

read(*,*) item1, item2, item3...

print *, item1, item2, item3

write(*,*) item1, item2, item3...हालाँकि, स्वरूपित I / O आपको डेटा स्थानांतरण पर अधिक लचीलापन देता है।

स्वरूपित इनपुट आउटपुट

प्रारूपित इनपुट आउटपुट में सिंटैक्स निम्नानुसार है -

read fmt, variable_list

print fmt, variable_list

write fmt, variable_listकहाँ पे,

fmt प्रारूप विनिर्देश है

वेरिएबल-लिस्ट, कीबोर्ड से पढ़ी जाने वाली वेरिएबल्स की एक सूची है या स्क्रीन पर लिखी गई है

प्रारूप विनिर्देश उस तरीके को परिभाषित करता है जिसमें स्वरूपित डेटा प्रदर्शित होता है। इसमें एक स्ट्रिंग होती है, जिसमें एक सूची होती हैedit descriptors कोष्ठकों में।

एक edit descriptor सटीक प्रारूप को निर्दिष्ट करता है, उदाहरण के लिए, दशमलव बिंदु आदि के बाद चौड़ाई, अंक, जिसमें वर्ण और संख्याएं प्रदर्शित की जाती हैं।

उदाहरण के लिए

Print "(f6.3)", piनिम्न तालिका वर्णनकर्ताओं का वर्णन करती है -

| डिस्क्रिप्टर | विवरण | उदाहरण |

|---|---|---|

| मैं | इसका उपयोग पूर्णांक आउटपुट के लिए किया जाता है। यह 'rIw.m' का रूप लेता है, जहाँ r, w और m का अर्थ नीचे दी गई तालिका में दिया गया है। पूर्णांक मूल्य सही हैं ger अपने। एल्ड्स में एड। यदि एक पूर्णांक को समायोजित करने के लिए an बड़ी चौड़ाई पर्याप्त नहीं है, तो fi eld तारांकन के साथ ld बड़ा है। |

प्रिंट "(3i5)", आई, जे, के |

| एफ | इसका उपयोग वास्तविक संख्या आउटपुट के लिए किया जाता है। यह 'rFw.d' फॉर्म लेता है जहाँ r, w और d का अर्थ नीचे दी गई तालिका में दिया गया है। वास्तविक मूल्य सही values in ed उनके। Elds में हैं। यदि वास्तविक संख्या को समायोजित करने के लिए the eld की चौड़ाई पर्याप्त नहीं है, तो fi eld को तारांकन के साथ ld लिया जाता है। |

प्रिंट "(f12.3)", पी |

| इ | यह घातीय संकेतन में वास्तविक आउटपुट के लिए उपयोग किया जाता है। 'ई' डिस्क्रिप्टर स्टेटमेंट 'rEw.d' का रूप लेता है, जहाँ आर, डब्ल्यू और डी के अर्थ नीचे दी गई तालिका में दिए गए हैं। वास्तविक मूल्य सही values in ed उनके। Elds में हैं। यदि वास्तविक संख्या को समायोजित करने के लिए the eld की चौड़ाई पर्याप्त नहीं है, तो fi eld को तारांकन के साथ ld लिया जाता है। कृपया ध्यान दें कि तीन दशमलव स्थानों के साथ वास्तविक संख्या का प्रिंट आउट करने के लिए कम से कम दस की of बड़ी चौड़ाई की आवश्यकता होती है। मंटिसा के संकेत के लिए एक, शून्य के लिए दो, मंटिसा के लिए चार और एक्सपोर्टर के लिए दो। सामान्य तौर पर, w + d + 7। |

प्रिंट "(e10.3)", 123456.0 '0.123e + 06' देता है |

| तों | इसका उपयोग वास्तविक आउटपुट (वैज्ञानिक संकेतन) के लिए किया जाता है। यह 'rESw.d' फॉर्म लेता है, जहाँ r, w और d का अर्थ नीचे दी गई तालिका में दिया गया है। 'ई' डिस्क्रिप्टर पारंपरिक डी 'वैज्ञानिक संकेतन' से पारंपरिक रूप से ज्ञात ff ers से थोड़ा ऊपर वर्णित है। साइंटि the सी नोटेशन में ई। डिस्क्रिप्टर के विपरीत 1.0 से 10.0 तक की रेंज में मंटिसा है जिसमें 0.1 से 1.0 की रेंज में मेंटिसा है। वास्तविक मूल्य सही values in ed उनके। Elds में हैं। यदि वास्तविक संख्या को समायोजित करने के लिए the eld की चौड़ाई पर्याप्त नहीं है, तो fi eld को तारांकन के साथ ld लिया जाता है। यहाँ भी, चौड़ाई must eld को ≥ d + 7 के व्यंजक को संतुष्ट करना चाहिए |

प्रिंट "(es10.3)", 123456.0 '1.235e + 05' देता है |

| ए | यह चरित्र आउटपुट के लिए उपयोग किया जाता है। यह 'rAw' का रूप लेता है जहाँ r और w के अर्थ नीचे दी गई तालिका में दिए गए हैं। चरित्र प्रकार सही types in ed उनके। Elds में हैं। यदि the eld की चौड़ाई वर्ण स्ट्रिंग को समायोजित करने के लिए पर्याप्त बड़ी नहीं है, तो fi eld स्ट्रिंग के 'rst ’w’ वर्णों के साथ lled है। |

प्रिंट "(a10)", str |

| एक्स | इसका उपयोग अंतरिक्ष उत्पादन के लिए किया जाता है। यह 'nX' का रूप लेता है, जहाँ 'n' वांछित स्थानों की संख्या है। |

प्रिंट "(5x, a10)", str |

| / | स्लैश डिस्क्रिप्टर - रिक्त लाइनों को सम्मिलित करने के लिए उपयोग किया जाता है। यह फॉर्म '/' लेता है और अगले डेटा आउटपुट को एक नई लाइन पर लाने के लिए बाध्य करता है। |

प्रिंट "(/, 5x, a10)", str |

प्रारूप वर्णनकर्ताओं के साथ निम्नलिखित प्रतीकों का उपयोग किया जाता है -

| अनु क्रमांक | प्रतीक और विवरण |

|---|---|

| 1 | c स्तंभ संख्या |

| 2 | d वास्तविक इनपुट या आउटपुट के लिए दशमलव स्थान के दाईं ओर अंकों की संख्या |

| 3 | m प्रदर्शित किए जाने वाले अंकों की न्यूनतम संख्या |

| 4 | n रिक्त स्थान की संख्या |

| 5 | r बार-बार गिनती - किसी डिस्क्रिप्टर या डिस्क्रिप्टर के समूह का उपयोग करने की संख्या |

| 6 | w फ़ील्ड की चौड़ाई - इनपुट या आउटपुट के लिए उपयोग किए जाने वाले वर्णों की संख्या |

उदाहरण 1

program printPi

pi = 3.141592653589793238

Print "(f6.3)", pi

Print "(f10.7)", pi

Print "(f20.15)", pi

Print "(e16.4)", pi/100

end program printPiजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

3.142

3.1415927

3.141592741012573

0.3142E-01उदाहरण 2

program printName

implicit none

character (len = 15) :: first_name

print *,' Enter your first name.'

print *,' Up to 20 characters, please'

read *,first_name

print "(1x,a)",first_name

end program printNameजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है: (मान लें कि उपयोगकर्ता ज़ारा नाम दर्ज करता है)

Enter your first name.

Up to 20 characters, please

Zaraउदाहरण 3

program formattedPrint

implicit none

real :: c = 1.2786456e-9, d = 0.1234567e3

integer :: n = 300789, k = 45, i = 2

character (len=15) :: str="Tutorials Point"

print "(i6)", k

print "(i6.3)", k

print "(3i10)", n, k, i

print "(i10,i3,i5)", n, k, i

print "(a15)",str

print "(f12.3)", d

print "(e12.4)", c

print '(/,3x,"n = ",i6, 3x, "d = ",f7.4)', n, d

end program formattedPrintजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

45

045

300789 45 2

300789 45 2

Tutorials Point

123.457

0.1279E-08

n = 300789 d = *******स्वरूप कथन

प्रारूप विवरण आपको एक कथन में वर्ण, पूर्णांक और वास्तविक आउटपुट को मिलाने और मिलान करने की अनुमति देता है। निम्न उदाहरण यह प्रदर्शित करता है -

program productDetails

implicit none

character (len = 15) :: name

integer :: id

real :: weight

name = 'Ardupilot'

id = 1

weight = 0.08

print *,' The product details are'

print 100

100 format (7x,'Name:', 7x, 'Id:', 1x, 'Weight:')

print 200, name, id, weight

200 format(1x, a, 2x, i3, 2x, f5.2)

end program productDetailsजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

The product details are

Name: Id: Weight:

Ardupilot 1 0.08फोरट्रान आपको डेटा को पढ़ने और फ़ाइलों में डेटा लिखने की अनुमति देता है।

पिछले अध्याय में, आपने देखा है कि टर्मिनल से डेटा कैसे पढ़ें, और डेटा कैसे लिखें। इस अध्याय में आप फोरट्रान द्वारा प्रदान की गई फ़ाइल इनपुट और आउटपुट कार्यात्मकताओं का अध्ययन करेंगे।

आप एक या अधिक फ़ाइलों को पढ़ और लिख सकते हैं। OPEN, WRITE, READ और CLOSE स्टेटमेंट आपको इसे हासिल करने की अनुमति देते हैं।

फ़ाइलें खोलना और बंद करना

फ़ाइल का उपयोग करने से पहले आपको फ़ाइल को खोलना होगा। openकमांड का उपयोग पढ़ने या लिखने के लिए फाइल खोलने के लिए किया जाता है। कमांड का सबसे सरल रूप है -

open (unit = number, file = "name").हालाँकि, खुले कथन का एक सामान्य रूप हो सकता है -

open (list-of-specifiers)निम्न तालिका में सबसे अधिक उपयोग की जाने वाली विशिष्टताओं का वर्णन है -

| अनु क्रमांक | विनिर्देशक और विवरण |

|---|---|

| 1 | [UNIT=] u यूनिट नंबर u 9-99 की रेंज में कोई भी नंबर हो सकता है और यह फ़ाइल को इंगित करता है, आप किसी भी नंबर को चुन सकते हैं, लेकिन प्रोग्राम की हर खुली फाइल में एक यूनिक नंबर होना चाहिए। |

| 2 | IOSTAT= ios यह I / O स्थिति पहचानकर्ता है और पूर्णांक चर होना चाहिए। यदि खुला कथन सफल है, तो लौटाया गया ios मान शून्य-शून्य मान है। |

| 3 | ERR = err यह एक लेबल है जिस पर नियंत्रण किसी भी त्रुटि के मामले में कूदता है। |

| 4 | FILE = fname फ़ाइल का नाम, एक चरित्र स्ट्रिंग। |

| 5 | STATUS = sta यह फ़ाइल की पूर्व स्थिति दिखाता है। एक चरित्र स्ट्रिंग और तीन मूल्यों में से एक हो सकता है नया, OLD या SCRATCH। बंद या प्रोग्राम समाप्त होने पर एक खरोंच फ़ाइल बनाई और हटा दी जाती है। |

| 6 | ACCESS = acc यह फ़ाइल एक्सेस मोड है। दोनों में से कोई भी मान हो सकता है, SEQUENTIAL या DIRECT। डिफ़ॉल्ट अनुक्रमिक है। |

| 7 | FORM = frm यह फ़ाइल का स्वरूपण स्थिति देता है। दोनों में से कोई एक मान हो सकता है या असंबद्ध। डिफ़ॉल्ट UNFORMATTED है |

| 8 | RECL = rl यह प्रत्यक्ष पहुंच फ़ाइल में प्रत्येक रिकॉर्ड की लंबाई निर्दिष्ट करता है। |

फ़ाइल खोले जाने के बाद, इसे पढ़ने और लिखने के बयानों द्वारा पहुँचा जाता है। एक बार हो जाने के बाद, इसे बंद कर देना चाहिएclose बयान।

घनिष्ठ कथन में निम्नलिखित सिंटैक्स है -

close ([UNIT = ]u[,IOSTAT = ios,ERR = err,STATUS = sta])कृपया ध्यान दें कि कोष्ठक में पैरामीटर वैकल्पिक हैं।

Example

यह उदाहरण फ़ाइल में कुछ डेटा लिखने के लिए एक नई फ़ाइल खोलने को दर्शाता है।

program outputdata

implicit none

real, dimension(100) :: x, y

real, dimension(100) :: p, q

integer :: i

! data

do i=1,100

x(i) = i * 0.1

y(i) = sin(x(i)) * (1-cos(x(i)/3.0))

end do

! output data into a file

open(1, file = 'data1.dat', status = 'new')

do i=1,100

write(1,*) x(i), y(i)

end do

close(1)

end program outputdataजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह फ़ाइल data1.dat बनाता है और इसमें x और y सरणी मान लिखता है। और फिर फाइल को बंद कर देता है।

फ़ाइल से पढ़ना और लिखना

क्रमशः पढ़ने और लिखने वाले बयानों को क्रमशः एक फ़ाइल में पढ़ने और लिखने के लिए उपयोग किया जाता है।

उनके पास निम्नलिखित वाक्यविन्यास हैं -

read ([UNIT = ]u, [FMT = ]fmt, IOSTAT = ios, ERR = err, END = s)

write([UNIT = ]u, [FMT = ]fmt, IOSTAT = ios, ERR = err, END = s)उपरोक्त तालिका में अधिकांश बारीकियों पर पहले ही चर्चा की जा चुकी है।

END = s स्पेसियर एक स्टेटमेंट लेबल है जहां प्रोग्राम जंप करता है, जब यह एंड-ऑफ-फाइल तक पहुंचता है।

Example

यह उदाहरण एक फ़ाइल में पढ़ने और लिखने से दर्शाता है।

इस कार्यक्रम में हम फ़ाइल से पढ़ते हैं, हमने अंतिम उदाहरण में बनाया, data1.dat, और इसे स्क्रीन पर प्रदर्शित करें।

program outputdata

implicit none

real, dimension(100) :: x, y

real, dimension(100) :: p, q

integer :: i

! data

do i = 1,100

x(i) = i * 0.1

y(i) = sin(x(i)) * (1-cos(x(i)/3.0))

end do

! output data into a file

open(1, file = 'data1.dat', status='new')

do i = 1,100

write(1,*) x(i), y(i)

end do

close(1)

! opening the file for reading

open (2, file = 'data1.dat', status = 'old')

do i = 1,100

read(2,*) p(i), q(i)

end do

close(2)

do i = 1,100

write(*,*) p(i), q(i)

end do

end program outputdataजब उपरोक्त कोड संकलित और निष्पादित किया जाता है, तो यह निम्नलिखित परिणाम उत्पन्न करता है -

0.100000001 5.54589933E-05

0.200000003 4.41325130E-04

0.300000012 1.47636665E-03

0.400000006 3.45637114E-03

0.500000000 6.64328877E-03

0.600000024 1.12552457E-02

0.699999988 1.74576249E-02

0.800000012 2.53552198E-02

0.900000036 3.49861123E-02

1.00000000 4.63171229E-02

1.10000002 5.92407547E-02

1.20000005 7.35742599E-02

1.30000007 8.90605897E-02

1.39999998 0.105371222

1.50000000 0.122110792

1.60000002 0.138823599

1.70000005 0.155002072

1.80000007 0.170096487

1.89999998 0.183526158

2.00000000 0.194692180

2.10000014 0.202990443

2.20000005 0.207826138

2.29999995 0.208628103

2.40000010 0.204863414

2.50000000 0.196052119

2.60000014 0.181780845

2.70000005 0.161716297

2.79999995 0.135617107

2.90000010 0.103344671

3.00000000 6.48725405E-02

3.10000014 2.02930309E-02

3.20000005 -3.01767997E-02

3.29999995 -8.61928314E-02

3.40000010 -0.147283033

3.50000000 -0.212848678

3.60000014 -0.282169819

3.70000005 -0.354410470

3.79999995 -0.428629100

3.90000010 -0.503789663

4.00000000 -0.578774154

4.09999990 -0.652400017

4.20000029 -0.723436713

4.30000019 -0.790623367

4.40000010 -0.852691114

4.50000000 -0.908382416

4.59999990 -0.956472993

4.70000029 -0.995793998

4.80000019 -1.02525222

4.90000010 -1.04385209

5.00000000 -1.05071592

5.09999990 -1.04510069

5.20000029 -1.02641726

5.30000019 -0.994243503

5.40000010 -0.948338211

5.50000000 -0.888650239

5.59999990 -0.815326691

5.70000029 -0.728716135

5.80000019 -0.629372001

5.90000010 -0.518047631

6.00000000 -0.395693362

6.09999990 -0.263447165

6.20000029 -0.122622721

6.30000019 2.53026206E-02

6.40000010 0.178709000

6.50000000 0.335851669

6.59999990 0.494883657

6.70000029 0.653881252

6.80000019 0.810866773

6.90000010 0.963840425

7.00000000 1.11080539

7.09999990 1.24979746

7.20000029 1.37891412

7.30000019 1.49633956

7.40000010 1.60037732

7.50000000 1.68947268

7.59999990 1.76223695

7.70000029 1.81747139

7.80000019 1.85418403

7.90000010 1.87160957

8.00000000 1.86922085

8.10000038 1.84674001

8.19999981 1.80414569

8.30000019 1.74167395

8.40000057 1.65982044

8.50000000 1.55933595

8.60000038 1.44121361

8.69999981 1.30668485

8.80000019 1.15719533

8.90000057 0.994394958

9.00000000 0.820112705