Объектно-ориентированный Python - Краткое руководство

Языки программирования появляются постоянно, равно как и различные методологии. Объектно-ориентированное программирование - одна из таких методологий, которая стала довольно популярной за последние несколько лет.

В этой главе рассказывается об особенностях языка программирования Python, которые делают его объектно-ориентированным языком программирования.

Схема классификации языкового программирования

Python можно охарактеризовать с помощью методологий объектно-ориентированного программирования. На следующем изображении показаны характеристики различных языков программирования. Обратите внимание на особенности Python, которые делают его объектно-ориентированным.

| Классы Langauage | Категории | Langauages |

|---|---|---|

| Парадигма программирования | Процедурный | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go |

| Сценарии | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby | |

| Функциональный | Clojure, Eralang, Haskell, Scala | |

| Класс компиляции | Статический | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go, Haskell, Scala |

| Динамический | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang | |

| Тип Класс | Сильный | C #, java, Go, Python, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang, Haskell, Scala |

| Слабый | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Perl, Php | |

| Класс памяти | Удалось | Другие |

| Неуправляемый | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C |

Что такое объектно-ориентированное программирование?

Object Orientedсредства направлены на объекты. Другими словами, это означает, что функционально направлено на моделирование объектов. Это один из многих методов, используемых для моделирования сложных систем путем описания набора взаимодействующих объектов через их данные и поведение.

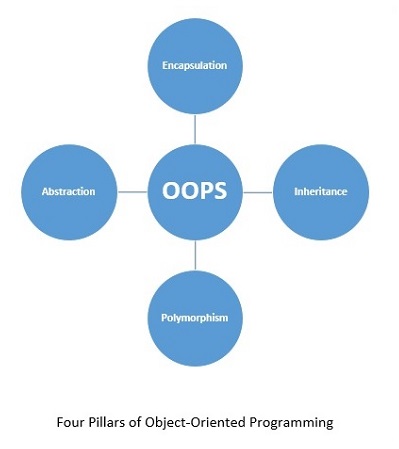

Python, объектно-ориентированное программирование (ООП), представляет собой способ программирования, который фокусируется на использовании объектов и классов для проектирования и создания приложений. Основными столпами объектно-ориентированного программирования (ООП) являются Inheritance, Polymorphism, Abstraction, объявление Encapsulation.

Объектно-ориентированный анализ (OOA) - это процесс изучения проблемы, системы или задачи и определения объектов и взаимодействий между ними.

Почему стоит выбрать объектно-ориентированное программирование?

Python был разработан с использованием объектно-ориентированного подхода. ООП предлагает следующие преимущества -

Предоставляет четкую структуру программы, которая упрощает отображение реальных проблем и способов их решения.

Облегчает обслуживание и модификацию существующего кода.

Повышает модульность программы, так как каждый объект существует независимо, и можно легко добавлять новые функции, не нарушая существующие.

Представляет собой хорошую основу для библиотек кода, в которой поставляемые компоненты могут быть легко адаптированы и изменены программистом.

Обеспечивает возможность повторного использования кода

Процедурное и объектно-ориентированное программирование

Процедурное программирование происходит от структурного программирования, основанного на концепциях functions/procedure/routines. В процедурно-ориентированном программировании легко получить доступ к данным и изменить их. С другой стороны, объектно-ориентированное программирование (ООП) позволяет разложить проблему на несколько единиц, называемыхobjectsа затем построить данные и функции вокруг этих объектов. Он уделяет больше внимания данным, чем процедурам или функциям. Также в ООП данные скрыты и недоступны для внешних процедур.

В таблице на следующем изображении показаны основные различия между подходами POP и OOP.

Разница между процедурно-ориентированным программированием (POP) и. Объектно-ориентированное программирование (ООП).

| Процедурно-ориентированное программирование | Объектно-ориентированного программирования | |

|---|---|---|

| На основе | В Pop все внимание уделяется данным и функциям | Упс основан на реальном сценарии. Вся программа разделена на небольшие части, называемые объектами. |

| Возможность повторного использования | Ограниченное повторное использование кода | Повторное использование кода |

| Подход | Нисходящий подход | Объектно-ориентированный дизайн |

| Спецификаторы доступа | Ни один | Общедоступный, частный и защищенный |

| Перемещение данных | Данные могут свободно перемещаться от функций к функциям в системе | В Oops данные могут перемещаться и взаимодействовать друг с другом через функции-члены |

| Доступ к данным | В pop большинство функций используют глобальные данные для обмена, к которым можно получить свободный доступ от функции к функции в системе. | К сожалению, данные не могут свободно перемещаться от метода к методу, они могут быть публичными или частными, поэтому мы можем контролировать доступ к данным. |

| Скрытие данных | В поп, такой специфический способ скрыть данные, немного менее безопасный | Он обеспечивает скрытие данных, что намного безопаснее |

| Перегрузка | Невозможно | Функции и перегрузка оператора |

| Примеры языков | C, VB, Фортран, Паскаль | C ++, Python, Java, C # |

| Абстракция | Использует абстракцию на уровне процедуры | Использует абстракцию на уровне класса и объекта |

Принципы объектно-ориентированного программирования

Объектно-ориентированное программирование (ООП) основано на концепции objects а не действия, и dataа не логика. Для того чтобы язык программирования был объектно-ориентированным, он должен иметь механизм, позволяющий работать с классами и объектами, а также реализовывать и использовать фундаментальные объектно-ориентированные принципы и концепции, а именно наследование, абстракцию, инкапсуляцию и полиморфизм.

Давайте вкратце разберемся с каждым из столпов объектно-ориентированного программирования -

Инкапсуляция

Это свойство скрывает ненужные детали и упрощает управление структурой программы. Реализация и состояние каждого объекта скрыты за четко определенными границами, что обеспечивает понятный и простой интерфейс для работы с ними. Один из способов добиться этого - сделать данные конфиденциальными.

Наследование

Наследование, также называемое обобщением, позволяет нам фиксировать иерархические отношения между классами и объектами. Например, «фрукт» - это обобщение слова «апельсин». Наследование очень полезно с точки зрения повторного использования кода.

Абстракция

Это свойство позволяет нам скрыть детали и раскрыть только существенные особенности концепции или объекта. Например, человек, управляющий скутером, знает, что при нажатии на рог издается звук, но он не имеет представления о том, как звук на самом деле создается при нажатии на рог.

Полиморфизм

Полиморфизм означает множество форм. То есть вещь или действие присутствует в разных формах или способами. Хороший пример полиморфизма - перегрузка конструктора в классах.

Объектно-ориентированный Python

В основе программирования на Python лежит object и OOP, однако вам не нужно ограничивать себя использованием ООП путем организации вашего кода в классы. ООП дополняет всю философию дизайна Python и поощряет чистый и прагматичный подход к программированию. ООП также позволяет писать большие и сложные программы.

Модули против классов и объектов

Модули похожи на «Словари»

При работе с модулями обратите внимание на следующие моменты -

Модуль Python - это пакет для инкапсуляции кода многократного использования.

Модули находятся в папке с __init__.py файл на нем.

Модули содержат функции и классы.

Модули импортируются с использованием import ключевое слово.

Напомним, что словарь - это key-valueпара. Это означает, что если у вас есть словарь с ключомEmployeID и вы хотите получить его, тогда вам придется использовать следующие строки кода -

employee = {“EmployeID”: “Employee Unique Identity!”}

print (employee [‘EmployeID])Вам нужно будет работать над модулями со следующим процессом -

Модуль - это файл Python с некоторыми функциями или переменными в нем.

Импортируйте нужный файл.

Теперь вы можете получить доступ к функциям или переменным в этом модуле с помощью символа '.' (dot) Оператор.

Рассмотрим модуль с именем employee.py с функцией в нем называется employee. Код функции приведен ниже -

# this goes in employee.py

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)Теперь импортируйте модуль, а затем получите доступ к функции EmployeID -

import employee

employee. EmployeID()Вы можете вставить в него переменную с именем Age, как показано -

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)

# just a variable

Age = “Employee age is **”Теперь получите доступ к этой переменной следующим образом -

import employee

employee.EmployeID()

print(employee.Age)Теперь сравним это со словарем -

Employee[‘EmployeID’] # get EmployeID from employee

Employee.employeID() # get employeID from the module

Employee.Age # get access to variableОбратите внимание, что в Python есть общий шаблон -

Взять key = value контейнер стиля

Получите что-нибудь по имени ключа

При сравнении модуля со словарем оба похожи, за исключением следующего:

В случае dictionary, ключ - это строка, а синтаксис - [ключ].

В случае module, ключ - это идентификатор, а синтаксис - .key.

Классы похожи на модули

Module - это специализированный словарь, в котором может храниться код Python, поэтому вы можете получить к нему доступ с помощью '.' Оператор. Класс - это способ взять группу функций и данных и поместить их в контейнер, чтобы вы могли получить к ним доступ с помощью оператора '.'.

Если вам нужно создать класс, похожий на модуль сотрудника, вы можете сделать это, используя следующий код -

class employee(object):

def __init__(self):

self. Age = “Employee Age is ##”

def EmployeID(self):

print (“This is just employee unique identity”)Note- Классы предпочтительнее модулей, потому что вы можете повторно использовать их такими, какие они есть, и без особого вмешательства. В то время как с модулями у вас есть только один со всей программой.

Объекты похожи на мини-импорт

Класс похож на mini-module и вы можете импортировать так же, как и для классов, используя концепцию под названием instantiate. Обратите внимание, что когда вы создаете экземпляр класса, вы получаетеobject.

Вы можете создать экземпляр объекта, аналогично вызову класса, например функции, как показано -

this_obj = employee() # Instantiatethis_obj.EmployeID() # get EmployeId from the class

print(this_obj.Age) # get variable AgeВы можете сделать это любым из следующих трех способов:

# dictionary style

Employee[‘EmployeID’]

# module style

Employee.EmployeID()

Print(employee.Age)

# Class style

this_obj = employee()

this_obj.employeID()

Print(this_obj.Age)В этой главе подробно рассказывается о настройке среды Python на вашем локальном компьютере.

Предварительные условия и наборы инструментов

Прежде чем продолжить изучение Python, мы предлагаем вам проверить, выполняются ли следующие предварительные условия:

На вашем компьютере установлена последняя версия Python

Установлена IDE или текстовый редактор

У вас есть базовые навыки написания и отладки на Python, то есть вы можете делать на Python следующее:

Умеет писать и запускать программы на Python.

Отлаживайте программы и диагностируйте ошибки.

Работа с основными типами данных.

Написать for петли, while петли и if заявления

Код functions

Если у вас нет опыта работы с языком программирования, вы можете найти множество руководств по Python для начинающих на

https://www.tutorialpoints.com/Установка Python

Следующие шаги подробно показывают, как установить Python на локальный компьютер.

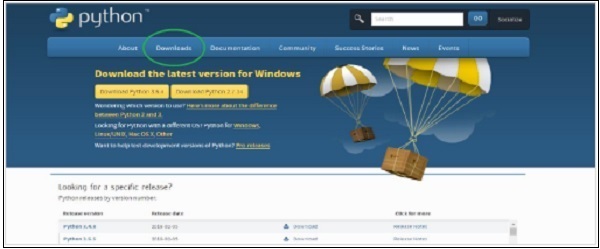

Step 1 - Перейдите на официальный сайт Python. https://www.python.org/, нажми на Downloads меню и выберите последнюю или любую стабильную версию по вашему выбору.

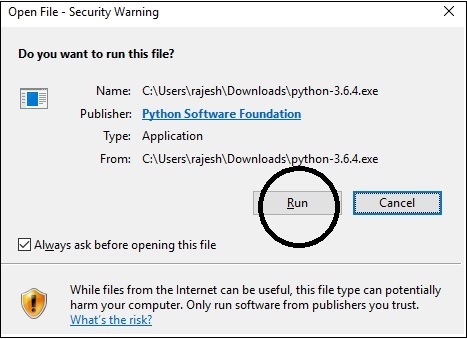

Step 2- Сохраните exe-файл установщика Python, который вы загружаете, и после его загрузки откройте его. Нажмите наRun и выберите Next вариант по умолчанию и завершить установку.

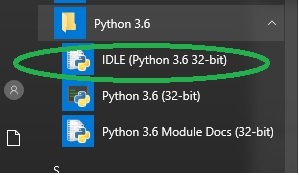

Step 3- После установки вы должны увидеть меню Python, как показано на изображении ниже. Запустите программу, выбрав IDLE (графический интерфейс Python).

Это запустит оболочку Python. Введите простые команды, чтобы проверить установку.

Выбор IDE

Интегрированная среда разработки - это текстовый редактор, предназначенный для разработки программного обеспечения. Вам нужно будет установить IDE для управления потоком вашего программирования и группировки проектов при работе над Python. Вот некоторые из IDE, доступных в Интернете. Вы можете выбрать тот, который вам удобнее.

- Pycharm IDE

- Komodo IDE

- Эрик Python IDE

Note - Eclipse IDE в основном используется на Java, однако у нее есть плагин для Python.

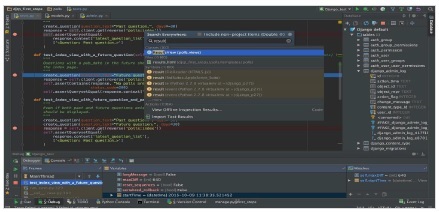

Pycharm

Pycharm, кроссплатформенная IDE, является одной из самых популярных IDE, доступных в настоящее время. Он обеспечивает помощь в кодировании и анализ с автозавершением кода, навигацией по проекту и коду, интегрированным модульным тестированием, интеграцией контроля версий, отладкой и многим другим

Ссылка для скачивания

https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/download/#section=windowsLanguages Supported - Python, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Coffee Script, TypeScript, Cython, AngularJS, Node.js, языки шаблонов.

Скриншот

Почему выбрать?

PyCharm предлагает своим пользователям следующие функции и преимущества:

- Кросс-платформенная IDE, совместимая с Windows, Linux и Mac OS

- Включает Django IDE, а также поддержку CSS и JavaScript

- Включает тысячи плагинов, встроенный терминал и контроль версий

- Интегрируется с Git, SVN и Mercurial

- Предлагает интеллектуальные инструменты редактирования для Python

- Простая интеграция с Virtualenv, Docker и Vagrant

- Простые функции навигации и поиска

- Анализ кода и рефакторинг

- Настраиваемые инъекции

- Поддерживает множество библиотек Python

- Содержит шаблоны и отладчики JavaScript

- Включает отладчики Python / Django

- Работает с Google App Engine, дополнительными фреймворками и библиотеками.

- Имеет настраиваемый пользовательский интерфейс, доступна эмуляция VIM

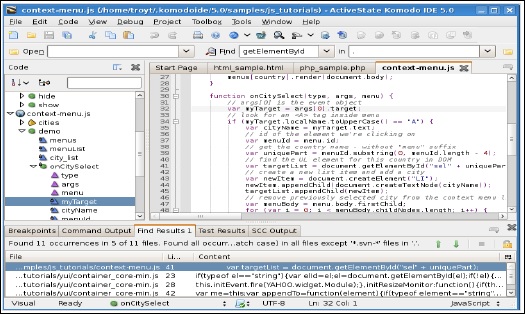

Komodo IDE

Это многоязычная IDE, которая поддерживает более 100 языков и в основном для динамических языков, таких как Python, PHP и Ruby. Это коммерческая среда IDE, доступная для 21-дневной бесплатной пробной версии с полной функциональностью. ActiveState - компания-разработчик программного обеспечения, управляющая разработкой Komodo IDE. Он также предлагает урезанную версию Komodo, известную как Komodo Edit, для простых задач программирования.

Эта среда IDE содержит все виды функций от самого базового до продвинутого уровня. Если вы студент или фрилансер, то вы можете купить его почти вдвое дешевле. Однако это совершенно бесплатно для преподавателей и профессоров из признанных институтов и университетов.

В нем есть все функции, необходимые для веб-разработки и разработки мобильных приложений, включая поддержку всех ваших языков и фреймворков.

Ссылка для скачивания

Ссылки для скачивания Komodo Edit (бесплатная версия) и Komodo IDE (платная версия) приведены здесь -

Komodo Edit (free)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-editKomodo IDE (paid)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-ide/downloads/ideСкриншот

Почему выбрать?

- Мощная IDE с поддержкой Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby и многих других.

- Кросс-платформенная IDE.

Он включает в себя основные функции, такие как встроенная поддержка отладчика, автозаполнение, средство просмотра объектной модели документа (DOM), браузер кода, интерактивные оболочки, конфигурация точки останова, профилирование кода, интегрированное модульное тестирование. Короче говоря, это профессиональная IDE с множеством функций, повышающих производительность.

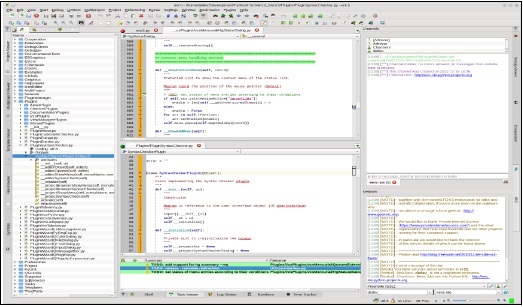

Эрик Python IDE

Это IDE с открытым исходным кодом для Python и Ruby. Эрик - полнофункциональный редактор и IDE, написанный на Python. Он основан на кроссплатформенном наборе инструментов Qt GUI, объединяющем очень гибкий элемент управления редактора Scintilla. IDE очень настраиваема, и можно выбирать, что использовать, а что нет. Вы можете скачать Eric IDE по ссылке ниже:

https://eric-ide.python-projects.org/eric-download.htmlПочему выбрать

- Отличные отступы, выделение ошибок.

- Код помощи

- Завершение кода

- Очистка кода с помощью PyLint

- Быстрый поиск

- Встроенный отладчик Python.

Скриншот

Выбор текстового редактора

Вам не всегда может понадобиться IDE. Для таких задач, как обучение программированию на Python или Arduino или при работе над быстрым сценарием в сценарии оболочки, который поможет вам автоматизировать некоторые задачи, подойдет простой и легкий текстовый редактор, ориентированный на код. Также многие текстовые редакторы предлагают такие функции, как подсветка синтаксиса и выполнение сценариев в программе, аналогичные IDE. Некоторые из текстовых редакторов приведены здесь -

- Atom

- Возвышенный текст

- Notepad++

Текстовый редактор Atom

Atom - это текстовый редактор, который можно взломать, созданный командой GitHub. Это бесплатный редактор текста и кода с открытым исходным кодом, что означает, что весь код доступен для чтения, изменения для собственного использования и даже внесения улучшений. Это кроссплатформенный текстовый редактор, совместимый с macOS, Linux и Microsoft Windows, с поддержкой надстроек, написанных на Node.js, и встроенного Git Control.

Ссылка для скачивания

https://atom.io/Скриншот

Поддерживаемые языки

C / C ++, C #, CSS, CoffeeScript, HTML, JavaScript, Java, JSON, Julia, Objective-C, PHP, Perl, Python, Ruby on Rails, Ruby, Shell script, Scala, SQL, XML, YAML и многие другие.

Превосходный текстовый редактор

Sublime text - это проприетарное программное обеспечение, которое предлагает вам бесплатную пробную версию, чтобы протестировать ее перед покупкой. По данным stackoverflow.com , это четвертая по популярности среда разработки.

Некоторые из его преимуществ - невероятная скорость, простота использования и поддержка сообщества. Он также поддерживает множество языков программирования и языков разметки, а функции могут быть добавлены пользователями с помощью плагинов, обычно создаваемых сообществом и поддерживаемых по лицензиям на бесплатное программное обеспечение.

Скриншот

Поддерживаемый язык

- Python, Ruby, JavaScript и т. Д.

Почему выбрать?

Настройте привязки клавиш, меню, фрагменты, макросы, дополнения и многое другое.

Функция автозаполнения

- Быстро вставляйте текст и код с помощью фрагментов превосходного текста, используя фрагменты, маркеры полей и заполнители

Открывается быстро

Кросс-платформенная поддержка Mac, Linux и Windows.

Переместите курсор туда, куда вы хотите перейти

Выберите несколько строк, слов и столбцов

Блокнот ++

Это бесплатный редактор исходного кода и замена Блокнота, который поддерживает несколько языков от ассемблера до XML, включая Python. Работает в среде MS Windows, его использование регулируется лицензией GPL. В дополнение к подсветке синтаксиса Notepad ++ имеет некоторые функции, которые особенно полезны для программистов.

Скриншот

Ключевая особенность

- Подсветка синтаксиса и сворачивание синтаксиса

- PCRE (Perl-совместимое регулярное выражение) Поиск / замена

- Полностью настраиваемый графический интерфейс

- SAuto завершение

- Редактирование с вкладками

- Multi-View

- Многоязычная среда

- Возможность запуска с разными аргументами

Поддерживаемый язык

- Почти все языки (более 60 языков), такие как Python, C, C ++, C #, Java и т. Д.

Структуры данных Python очень интуитивно понятны с синтаксической точки зрения и предлагают большой выбор операций. Вам необходимо выбрать структуру данных Python в зависимости от того, что включают в себя данные, если они должны быть изменены, или если это фиксированные данные и какой тип доступа требуется, например, в начале / конце / случайном и т. Д.

Списки

Список представляет собой наиболее универсальный тип структуры данных в Python. Список - это контейнер, который содержит значения (элементы или элементы), разделенные запятыми, в квадратных скобках. Списки полезны, когда мы хотим работать с несколькими связанными значениями. Поскольку списки хранят данные вместе, мы можем выполнять одни и те же методы и операции с несколькими значениями одновременно. Индексы списков начинаются с нуля и, в отличие от строк, списки изменяемы.

Структура данных - список

>>>

>>> # Any Empty List

>>> empty_list = []

>>>

>>> # A list of String

>>> str_list = ['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> # A list of Integers

>>> int_list = [1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>>

>>> #Mixed items list

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>> # To print the list

>>>

>>> print(empty_list)

[]

>>> print(str_list)

['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> print(type(str_list))

<class 'list'>

>>> print(int_list)

[1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>> print(mixed_list)

['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']Доступ к элементам в списке Python

Каждому элементу списка присваивается номер - то есть индекс или позиция этого номера. Индексирование всегда начинается с нуля, второй индекс равен единице и так далее. Чтобы получить доступ к элементам в списке, мы можем использовать эти номера индексов в квадратных скобках. Например, обратите внимание на следующий код -

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>>

>>> # To access the First Item of the list

>>> mixed_list[0]

'This'

>>> # To access the 4th item

>>> mixed_list[3]

18

>>> # To access the last item of the list

>>> mixed_list[-1]

'list'Пустые объекты

Пустые объекты - это самые простые и базовые встроенные типы Python. Мы использовали их несколько раз, не замечая этого, и распространили их на каждый созданный нами класс. Основная цель написания пустого класса - заблокировать что-то на время, а затем расширить и добавить к нему поведение.

Добавить поведение к классу означает заменить структуру данных объектом и изменить все ссылки на него. Поэтому важно проверить данные, не являются ли они замаскированным объектом, прежде чем что-либо создавать. Для лучшего понимания обратите внимание на следующий код:

>>> #Empty objects

>>>

>>> obj = object()

>>> obj.x = 9

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

obj.x = 9

AttributeError: 'object' object has no attribute 'x'Итак, сверху мы видим, что невозможно установить какие-либо атрибуты для объекта, который был создан напрямую. Когда Python позволяет объекту иметь произвольные атрибуты, требуется определенный объем системной памяти, чтобы отслеживать, какие атрибуты имеет каждый объект, для хранения как имени атрибута, так и его значения. Даже если атрибуты не сохранены, определенный объем памяти выделяется для потенциальных новых атрибутов.

Таким образом, Python по умолчанию отключает произвольные свойства объекта и несколько других встроенных функций.

>>> # Empty Objects

>>>

>>> class EmpObject:

pass

>>> obj = EmpObject()

>>> obj.x = 'Hello, World!'

>>> obj.x

'Hello, World!'Следовательно, если мы хотим сгруппировать свойства вместе, мы могли бы сохранить их в пустом объекте, как показано в приведенном выше коде. Однако этот метод не всегда предлагается. Помните, что классы и объекты следует использовать только тогда, когда вы хотите указать и данные, и поведение.

Кортежи

Кортежи похожи на списки и могут хранить элементы. Однако они неизменяемы, поэтому мы не можем добавлять, удалять или заменять объекты. Основные преимущества, которые дает кортеж благодаря его неизменности, заключаются в том, что мы можем использовать их в качестве ключей в словарях или в других местах, где объекту требуется хеш-значение.

Кортежи используются для хранения данных, а не поведения. Если вам требуется поведение для управления кортежем, вам нужно передать кортеж в функцию (или метод другого объекта), которая выполняет действие.

Поскольку кортеж может действовать как ключ словаря, сохраненные значения отличаются друг от друга. Мы можем создать кортеж, разделив значения запятой. Кортежи заключаются в круглые скобки, но не обязательно. В следующем коде показаны два идентичных назначения.

>>> stock1 = 'MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45

>>> stock2 = ('MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45)

>>> type (stock1)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> type(stock2)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> stock1 == stock2

True

>>>Определение кортежа

Кортежи очень похожи на список, за исключением того, что весь набор элементов заключен в круглые скобки вместо квадратных.

Точно так же, как когда вы разрезаете список, вы получаете новый список, а когда вы разрезаете кортеж, вы получаете новый кортеж.

>>> tupl = ('Tuple','is', 'an','IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl[0]

'Tuple'

>>> tupl[-1]

'list'

>>> tupl[1:3]

('is', 'an')Кортежные методы Python

В следующем коде показаны методы в кортежах Python -

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl.append('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#148>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.append('new')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

>>> tupl.remove('is')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#149>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.remove('is')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'remove'

>>> tupl.index('list')

4

>>> tupl.index('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#151>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.index('new')

ValueError: tuple.index(x): x not in tuple

>>> "is" in tupl

True

>>> tupl.count('is')

1Из кода, показанного выше, мы можем понять, что кортежи неизменяемы и, следовательно, -

Вы cannot добавить элементы в кортеж.

Вы cannot добавить или расширить метод.

Вы cannot удалить элементы из кортежа.

Кортежи имеют no remove или pop метод.

Подсчет и индекс - это методы, доступные в кортеже.

толковый словарь

Словарь - это один из встроенных типов данных Python, который определяет взаимно однозначные отношения между ключами и значениями.

Определение словарей

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять определение словаря:

>>> # empty dictionary

>>> my_dict = {}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with integer keys

>>> my_dict = { 1:'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with mixed keys

>>> my_dict = {'name': 'Aarav', 1: [ 2, 4, 10]}

>>>

>>> # using built-in function dict()

>>> my_dict = dict({1:'msft', 2:'IT'})

>>>

>>> # From sequence having each item as a pair

>>> my_dict = dict([(1,'msft'), (2,'IT')])

>>>

>>> # Accessing elements of a dictionary

>>> my_dict[1]

'msft'

>>> my_dict[2]

'IT'

>>> my_dict['IT']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#177>", line 1, in <module>

my_dict['IT']

KeyError: 'IT'

>>>Из приведенного выше кода мы можем заметить, что:

Сначала мы создаем словарь с двумя элементами и присваиваем его переменной my_dict. Каждый элемент представляет собой пару "ключ-значение", а весь набор элементов заключен в фигурные скобки.

Номер 1 это ключ и msftэто его ценность. Так же,2 это ключ и IT это его ценность.

Вы можете получить значения по ключу, но не наоборот. Таким образом, когда мы пытаемсяmy_dict[‘IT’] , возникает исключение, потому что IT это не ключ.

Изменение словарей

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять, как изменить словарь:

>>> # Modifying a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>> my_dict[2] = 'Software'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software'}

>>>

>>> my_dict[3] = 'Microsoft Technologies'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}Из приведенного выше кода мы можем заметить, что -

У вас не может быть повторяющихся ключей в словаре. Изменение значения существующего ключа приведет к удалению старого значения.

Вы можете добавить новые пары "ключ-значение" в любое время.

В словарях нет понятия порядка между элементами. Это простые неупорядоченные коллекции.

Смешивание типов данных в словаре

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять, как смешивать типы данных в словаре:

>>> # Mixing Data Types in a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}

>>> my_dict[4] = 'Operating System'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>> my_dict['Bill Gates'] = 'Owner'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}Из приведенного выше кода мы можем заметить, что -

Не только строки, но и значение словаря могут иметь любой тип данных, включая строки, целые числа, включая сам словарь.

В отличие от значений словаря, ключи словаря более ограничены, но могут быть любого типа, например строки, целые числа или любой другой.

Удаление элементов из словарей

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять, как удалять элементы из словаря:

>>> # Deleting Items from a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}

>>>

>>> del my_dict['Bill Gates']

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>>

>>> my_dict.clear()

>>> my_dict

{}Из приведенного выше кода мы можем заметить, что -

del - позволяет удалять отдельные элементы из словаря по ключу.

clear - удаляет все элементы из словаря.

Наборы

Set () - это неупорядоченная коллекция без повторяющихся элементов. Хотя отдельные элементы неизменяемы, сам набор является изменяемым, то есть мы можем добавлять или удалять элементы / элементы из набора. Мы можем выполнять математические операции, такие как объединение, пересечение и т. Д. С set.

Хотя наборы в целом могут быть реализованы с использованием деревьев, набор в Python может быть реализован с использованием хэш-таблицы. Это позволяет получить высокооптимизированный метод проверки, содержится ли в наборе конкретный элемент.

Создание набора

Набор создается путем помещения всех предметов (элементов) в фигурные скобки. {}, через запятую или с помощью встроенной функции set(). Обратите внимание на следующие строки кода -

>>> #set of integers

>>> my_set = {1,2,4,8}

>>> print(my_set)

{8, 1, 2, 4}

>>>

>>> #set of mixed datatypes

>>> my_set = {1.0, "Hello World!", (2, 4, 6)}

>>> print(my_set)

{1.0, (2, 4, 6), 'Hello World!'}

>>>Методы для множеств

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять методы для наборов -

>>> >>> #METHODS FOR SETS

>>>

>>> #add(x) Method

>>> topics = {'Python', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>> topics.add('C++')

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>>

>>> #union(s) Method, returns a union of two set.

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>> team = {'Developer', 'Content Writer', 'Editor','Tester'}

>>> group = topics.union(team)

>>> group

{'Tester', 'C#', 'Python', 'Editor', 'Developer', 'C++', 'Java', 'Content

Writer'}

>>> # intersets(s) method, returns an intersection of two sets

>>> inters = topics.intersection(team)

>>> inters

set()

>>>

>>> # difference(s) Method, returns a set containing all the elements of

invoking set but not of the second set.

>>>

>>> safe = topics.difference(team)

>>> safe

{'Python', 'C++', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>>

>>> diff = topics.difference(group)

>>> diff

set()

>>> #clear() Method, Empties the whole set.

>>> group.clear()

>>> group

set()

>>>Операторы для множеств

Обратите внимание на следующий код, чтобы понять операторы для наборов -

>>> # PYTHON SET OPERATIONS

>>>

>>> #Creating two sets

>>> set1 = set()

>>> set2 = set()

>>>

>>> # Adding elements to set

>>> for i in range(1,5):

set1.add(i)

>>> for j in range(4,9):

set2.add(j)

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set2

{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Union of set1 and set2

>>> set3 = set1 | set2 # same as set1.union(set2)

>>> print('Union of set1 & set2: set3 = ', set3)

Union of set1 & set2: set3 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Intersection of set1 & set2

>>> set4 = set1 & set2 # same as set1.intersection(set2)

>>> print('Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = ', set4)

Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = {4}

>>>

>>> # Checking relation between set3 and set4

>>> if set3 > set4: # set3.issuperset(set4)

print('Set3 is superset of set4')

elif set3 < set4: #set3.issubset(set4)

print('Set3 is subset of set4')

else: #set3 == set4

print('Set 3 is same as set4')

Set3 is superset of set4

>>>

>>> # Difference between set3 and set4

>>> set5 = set3 - set4

>>> print('Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = ', set5)

Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> # Check if set4 and set5 are disjoint sets

>>> if set4.isdisjoint(set5):

print('Set4 and set5 have nothing in common\n')

Set4 and set5 have nothing in common

>>> # Removing all the values of set5

>>> set5.clear()

>>> set5 set()В этой главе мы подробно обсудим объектно-ориентированные термины и концепции программирования. Класс - это просто фабрика для примера. Эта фабрика содержит схему, описывающую, как создавать экземпляры. Экземпляры или объект создаются из класса. В большинстве случаев у нас может быть более одного экземпляра класса. Каждый экземпляр имеет набор атрибутов, и эти атрибуты определены в классе, поэтому ожидается, что каждый экземпляр конкретного класса будет иметь одинаковые атрибуты.

Наборы классов: поведение и состояние

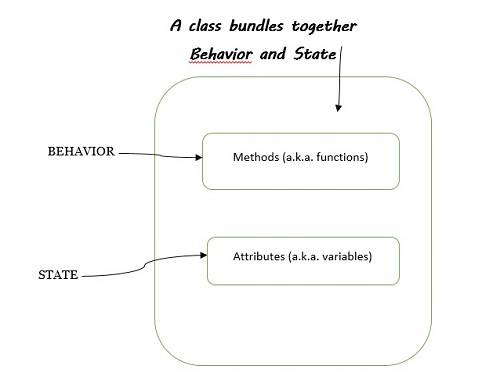

Класс позволит вам связать поведение и состояние объекта. Обратите внимание на следующую диаграмму для лучшего понимания -

При обсуждении наборов классов следует обратить внимание на следующие моменты:

Слово behavior идентичен function - это кусок кода, который что-то делает (или реализует поведение)

Слово state идентичен variables - это место для хранения значений внутри класса.

Когда мы вместе утверждаем поведение и состояние класса, это означает, что класс упаковывает функции и переменные.

У классов есть методы и атрибуты

В Python создание метода определяет поведение класса. Слово метод - это ООП-имя, присвоенное функции, определенной в классе. Подводя итог -

Class functions - синоним methods

Class variables - синоним name attributes.

Class - план экземпляра с точным поведением.

Object - один из экземпляров класса, выполняющий функции, определенные в классе.

Type - указывает класс, к которому принадлежит экземпляр

Attribute - Любое значение объекта: object.attribute

Method - «вызываемый атрибут», определенный в классе

Например, обратите внимание на следующий фрагмент кода -

var = “Hello, John”

print( type (var)) # < type ‘str’> or <class 'str'>

print(var.upper()) # upper() method is called, HELLO, JOHNСоздание и реализация

В следующем коде показано, как создать наш первый класс, а затем его экземпляр.

class MyClass(object):

pass

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj)Здесь мы создали класс под названием MyClassи который не выполняет никаких задач. Аргументobject в MyClass class включает наследование классов и будет обсуждаться в следующих главах. pass в приведенном выше коде указывает, что этот блок пуст, то есть это определение пустого класса.

Создадим экземпляр this_obj из MyClass() class и распечатайте его, как показано -

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x03B08E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x0369D390>Здесь мы создали экземпляр MyClass.Шестнадцатеричный код относится к адресу, где хранится объект. Другой экземпляр указывает на другой адрес.

Теперь давайте определим одну переменную внутри класса MyClass() и получите переменную из экземпляра этого класса, как показано в следующем коде -

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj.var)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj.var)Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

9

9Поскольку экземпляр знает, из какого класса он создан, поэтому при запросе атрибута из экземпляра экземпляр ищет атрибут и класс. Это называетсяattribute lookup.

Методы экземпляра

Функция, определенная в классе, называется method.Метод экземпляра требует экземпляра для его вызова и не требует декоратора. При создании метода экземпляра первым параметром всегда являетсяself. Хотя мы можем называть его (себя) любым другим именем, рекомендуется использовать self, поскольку это соглашение об именах.

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

obj = MyClass()

print(obj.var)

obj.firstM()Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

9

hello, WorldОбратите внимание, что в приведенной выше программе мы определили метод с self в качестве аргумента. Но мы не можем вызвать метод, поскольку не объявили для него никаких аргументов.

class MyClass(object):

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

print(self)

obj = MyClass()

obj.firstM()

print(obj)Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

hello, World

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>Инкапсуляция

Инкапсуляция - одна из основ ООП. ООП позволяет нам скрыть сложность внутренней работы объекта, которая выгодна разработчику, следующими способами:

Упрощает и упрощает понимание использования объекта без знания внутреннего устройства.

Любое изменение легко управляемо.

Объектно-ориентированное программирование сильно зависит от инкапсуляции. Термины инкапсуляция и абстракция (также называемые сокрытием данных) часто используются как синонимы. Они почти синонимы, поскольку абстракция достигается за счет инкапсуляции.

Инкапсуляция предоставляет нам механизм ограничения доступа к некоторым компонентам объекта, это означает, что внутреннее представление объекта не может быть видно извне определения объекта. Доступ к этим данным обычно достигается с помощью специальных методов -Getters и Setters.

Эти данные хранятся в атрибутах экземпляра, и ими можно управлять из любого места за пределами класса. Для его защиты доступ к этим данным должен осуществляться только с помощью методов экземпляра. Прямой доступ не допускается.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.age

zack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

45

Fourty FiveДанные должны храниться только в том случае, если они верны и действительны, с использованием конструкций обработки исключений. Как мы видим выше, ограничений на ввод данных в метод setAge () пользователем нет. Это может быть строка, число или список. Поэтому нам нужно проверить приведенный выше код, чтобы убедиться в правильности сохранения.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.agezack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Конструктор инициализации

__init__ метод неявно вызывается, как только создается экземпляр объекта класса. Это инициализирует объект.

x = MyClass()Строка кода, показанная выше, создаст новый экземпляр и назначит этот объект локальной переменной x.

Операция создания экземпляра, то есть calling a class object, создает пустой объект. Многие классы любят создавать объекты с экземплярами, настроенными для определенного начального состояния. Следовательно, класс может определять специальный метод с именем __init __ (), как показано:

def __init__(self):

self.data = []Python вызывает __init__ во время создания экземпляра, чтобы определить дополнительный атрибут, который должен возникать при создании экземпляра класса, который может устанавливать некоторые начальные значения для этого объекта или запускать процедуру, требуемую при создании экземпляра. Итак, в этом примере новый инициализированный экземпляр можно получить:

x = MyClass()Метод __init __ () может иметь один или несколько аргументов для большей гибкости. Init означает инициализацию, поскольку он инициализирует атрибуты экземпляра. Он называется конструктором класса.

class myclass(object):

def __init__(self,aaa, bbb):

self.a = aaa

self.b = bbb

x = myclass(4.5, 3)

print(x.a, x.b)Вывод

4.5 3Атрибуты класса

Атрибут, определенный в классе, называется «атрибутами класса», а атрибуты, определенные в функции, называются «атрибутами экземпляра». При определении эти атрибуты не имеют префикса self, так как это свойство класса, а не конкретного экземпляра.

К атрибутам класса может получить доступ сам класс (имя_класса. Имя_атрибута), а также экземпляры класса (имя_атрибута). Таким образом, экземпляры имеют доступ как к атрибутам экземпляра, так и к атрибутам класса.

>>> class myclass():

age = 21

>>> myclass.age

21

>>> x = myclass()

>>> x.age

21

>>>Атрибут класса можно переопределить в экземпляре, даже если это не лучший метод для прерывания инкапсуляции.

В Python есть путь поиска атрибутов. Первый - это метод, определенный внутри класса, а затем класс над ним.

>>> class myclass(object):

classy = 'class value'

>>> dd = myclass()

>>> print (dd.classy) # This should return the string 'class value'

class value

>>>

>>> dd.classy = "Instance Value"

>>> print(dd.classy) # Return the string "Instance Value"

Instance Value

>>>

>>> # This will delete the value set for 'dd.classy' in the instance.

>>> del dd.classy

>>> >>> # Since the overriding attribute was deleted, this will print 'class

value'.

>>> print(dd.classy)

class value

>>>Мы переопределяем атрибут класса «классный» в экземпляре dd. Когда он переопределен, интерпретатор Python считывает переопределенное значение. Но как только новое значение удаляется с помощью 'del', переопределенное значение больше не присутствует в экземпляре, и, следовательно, поиск идет на уровень выше и получает его из класса.

Работа с данными классов и экземпляров

В этом разделе давайте разберемся, как данные класса связаны с данными экземпляра. Мы можем хранить данные либо в классе, либо в экземпляре. Когда мы проектируем класс, мы решаем, какие данные принадлежат экземпляру и какие данные должны храниться в общем классе.

Экземпляр может получить доступ к данным класса. Если мы создадим несколько экземпляров, то эти экземпляры смогут получить доступ к своим индивидуальным значениям атрибутов, а также ко всем данным класса.

Таким образом, данные класса - это данные, которые используются всеми экземплярами. Соблюдайте приведенный ниже код для лучшего понимания -

class InstanceCounter(object):

count = 0 # class attribute, will be accessible to all instances

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

InstanceCounter.count +=1 # Increment the value of class attribute, accessible through class name

# In above line, class ('InstanceCounter') act as an object

def set_val(self, newval):

self.val = newval

def get_val(self):

return self.val

def get_count(self):

return InstanceCounter.count

a = InstanceCounter(9)

b = InstanceCounter(18)

c = InstanceCounter(27)

for obj in (a, b, c):

print ('val of obj: %s' %(obj.get_val())) # Initialized value ( 9, 18, 27)

print ('count: %s' %(obj.get_count())) # always 3Вывод

val of obj: 9

count: 3

val of obj: 18

count: 3

val of obj: 27

count: 3Короче говоря, атрибуты класса одинаковы для всех экземпляров класса, тогда как атрибуты экземпляра являются индивидуальными для каждого экземпляра. Для двух разных экземпляров у нас будет два разных атрибута экземпляра.

class myClass:

class_attribute = 99

def class_method(self):

self.instance_attribute = 'I am instance attribute'

print (myClass.__dict__)Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

{'__module__': '__main__', 'class_attribute': 99, 'class_method': <function myClass.class_method at 0x04128D68>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__doc__': None}Атрибут экземпляра myClass.__dict__ как показано -

>>> a = myClass()

>>> a.class_method()

>>> print(a.__dict__)

{'instance_attribute': 'I am instance attribute'}В этой главе подробно рассказывается о различных встроенных функциях Python, операциях файлового ввода-вывода и концепциях перегрузки.

Встроенные функции Python

Интерпретатор Python имеет ряд функций, называемых встроенными функциями, которые легко доступны для использования. В своей последней версии Python содержит 68 встроенных функций, перечисленных в таблице ниже -

| ВСТРОЕННЫЕ ФУНКЦИИ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| абс () | dict () | Помогите() | мин () | setattr () |

| все() | dir () | шестнадцатеричный () | следующий() | ломтик() |

| Любые() | divmod () | Я бы() | объект () | отсортировано () |

| ascii () | перечислить () | ввод () | окт () | staticmethod () |

| bin () | eval () | int () | открытый() | str () |

| bool () | exec () | isinstance () | ord () | сумма () |

| bytearray () | фильтр() | issubclass () | pow () | супер() |

| байты () | float () | iter () | Распечатать() | кортеж () |

| вызываемый () | формат() | len () | свойство() | тип() |

| chr () | Frozenset () | список() | спектр() | vars () |

| classmethod () | getattr () | местные жители () | repr () | zip () |

| compile () | глобалы () | карта() | обратный () | __импорт__() |

| сложный() | hasattr () | Максимум() | круглый() | |

| delattr () | хэш () | memoryview () | набор() | |

В этом разделе кратко обсуждаются некоторые важные функции -

функция len ()

Функция len () получает длину строк, списка или коллекций. Он возвращает длину или количество элементов объекта, где объект может быть строкой, списком или коллекцией.

>>> len(['hello', 9 , 45.0, 24])

4Функция len () внутренне работает как list.__len__() или же tuple.__len__(). Таким образом, обратите внимание, что len () работает только с объектами, имеющими __len__() метод.

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set1.__len__()

4Однако на практике мы предпочитаем len() вместо __len__() функционируют по следующим причинам -

Это более эффективно. И совсем не обязательно, чтобы был написан конкретный метод для отказа в доступе к специальным методам, таким как __len__.

Легко обслуживать.

Поддерживает обратную совместимость.

Обратный (seq)

Он возвращает обратный итератор. seq должен быть объектом, который имеет метод __reversed __ () или поддерживает протокол последовательности (метод __len __ () и метод __getitem __ ()). Обычно он используется вfor зацикливается, когда мы хотим перебрать элементы сзади наперед.

>>> normal_list = [2, 4, 5, 7, 9]

>>>

>>> class CustomSequence():

def __len__(self):

return 5

def __getitem__(self,index):

return "x{0}".format(index)

>>> class funkyback():

def __reversed__(self):

return 'backwards!'

>>> for seq in normal_list, CustomSequence(), funkyback():

print('\n{}: '.format(seq.__class__.__name__), end="")

for item in reversed(seq):

print(item, end=", ")Цикл for в конце печатает перевернутый список обычного списка и экземпляры двух пользовательских последовательностей. Вывод показывает, чтоreversed() работает со всеми тремя из них, но дает совсем другие результаты, когда мы определяем __reversed__.

Вывод

Вы можете наблюдать следующий результат, когда выполняете приведенный выше код -

list: 9, 7, 5, 4, 2,

CustomSequence: x4, x3, x2, x1, x0,

funkyback: b, a, c, k, w, a, r, d, s, !,Перечислить

В enumerate () добавляет счетчик к итерируемому объекту и возвращает объект перечисления.

Синтаксис enumerate () -

enumerate(iterable, start = 0)Здесь второй аргумент start не является обязательным, и по умолчанию индекс начинается с нуля (0).

>>> # Enumerate

>>> names = ['Rajesh', 'Rahul', 'Aarav', 'Sahil', 'Trevor']

>>> enumerate(names)

<enumerate object at 0x031D9F80>

>>> list(enumerate(names))

[(0, 'Rajesh'), (1, 'Rahul'), (2, 'Aarav'), (3, 'Sahil'), (4, 'Trevor')]

>>>Так enumerate()возвращает итератор, который возвращает кортеж, в котором хранится количество элементов в переданной последовательности. Поскольку возвращаемое значение - итератор, прямой доступ к нему не очень полезен. Лучшим подходом для enumerate () является ведение счетчика в цикле for.

>>> for i, n in enumerate(names):

print('Names number: ' + str(i))

print(n)

Names number: 0

Rajesh

Names number: 1

Rahul

Names number: 2

Aarav

Names number: 3

Sahil

Names number: 4

TrevorВ стандартной библиотеке есть много других функций, и вот еще один список некоторых более широко используемых функций:

hasattr, getattr, setattr и delattr, который позволяет управлять атрибутами объекта по их строковым именам.

all и any, которые принимают итерируемый объект и возвращают True если все или любой из пунктов оцениваются как истинные.

nzip, который принимает две или более последовательностей и возвращает новую последовательность кортежей, где каждый кортеж содержит одно значение из каждой последовательности.

Файловый ввод-вывод

Понятие файлов связано с термином объектно-ориентированное программирование. Python обернул интерфейс, предоставляемый операционными системами, в абстракцию, которая позволяет нам работать с файловыми объектами.

В open()встроенная функция используется для открытия файла и возврата файлового объекта. Это наиболее часто используемая функция с двумя аргументами -

open(filename, mode)Функция open () вызывает два аргумента: первый - имя файла, а второй - режим. Здесь mode может быть 'r' для режима только для чтения, 'w' только для записи (существующий файл с тем же именем будет удален), а 'a' открывает файл для добавления, любые данные, записанные в файл, добавляются автоматически. к концу. 'r +' открывает файл для чтения и записи. Режим по умолчанию доступен только для чтения.

В Windows добавление «b» к режиму открывает файл в двоичном режиме, поэтому существуют также такие режимы, как «rb», «wb» и «r + b».

>>> text = 'This is the first line'

>>> file = open('datawork','w')

>>> file.write(text)

22

>>> file.close()В некоторых случаях мы просто хотим добавить к существующему файлу, а не перезаписывать его, для этого мы можем указать значение 'a' в качестве аргумента режима, чтобы добавить его в конец файла, а не полностью перезаписывать существующий файл. содержание.

>>> f = open('datawork','a')

>>> text1 = ' This is second line'

>>> f.write(text1)

20

>>> f.close()Когда файл открыт для чтения, мы можем вызвать метод read, readline или readlines, чтобы получить содержимое файла. Метод чтения возвращает все содержимое файла в виде объекта str или bytes, в зависимости от того, является ли второй аргумент «b».

Для удобства чтения и во избежание чтения большого файла за один присест часто лучше использовать цикл for непосредственно для файлового объекта. Для текстовых файлов он будет читать каждую строку по одной, и мы можем обрабатывать ее внутри тела цикла. Однако для двоичных файлов лучше читать фрагменты данных фиксированного размера с помощью метода read (), передавая параметр для максимального числа байтов для чтения.

>>> f = open('fileone','r+')

>>> f.readline()

'This is the first line. \n'

>>> f.readline()

'This is the second line. \n'При записи в файл с помощью метода записи для файловых объектов в файл записывается строковый (байты для двоичных данных) объект. Метод Writelines принимает последовательность строк и записывает каждое из повторяемых значений в файл. Метод Writelines не добавляет новую строку после каждого элемента в последовательности.

Наконец, когда мы закончим чтение или запись файла, следует вызвать метод close (), чтобы убедиться, что все буферизованные записи записываются на диск, что файл был должным образом очищен и все ресурсы, связанные с файлом, возвращаются обратно в операционная система. Лучше вызвать метод close (), но технически это произойдет автоматически, когда скрипт существует.

Альтернатива перегрузке метода

Под перегрузкой метода понимается наличие нескольких методов с одним и тем же именем, которые принимают разные наборы аргументов.

Для одного метода или функции мы можем сами указать количество параметров. В зависимости от определения функции она может вызываться с нулем, одним, двумя или более параметрами.

class Human:

def sayHello(self, name = None):

if name is not None:

print('Hello ' + name)

else:

print('Hello ')

#Create Instance

obj = Human()

#Call the method, else part will be executed

obj.sayHello()

#Call the method with a parameter, if part will be executed

obj.sayHello('Rahul')Вывод

Hello

Hello RahulАргументы по умолчанию

Функции тоже являются объектами

Вызываемый объект - это объект, который может принимать некоторые аргументы и, возможно, вернет объект. Функция - это самый простой вызываемый объект в Python, но есть и другие, такие как классы или определенные экземпляры классов.

Каждая функция в Python - это объект. Объекты могут содержать методы или функции, но объект не обязательно является функцией.

def my_func():

print('My function was called')

my_func.description = 'A silly function'

def second_func():

print('Second function was called')

second_func.description = 'One more sillier function'

def another_func(func):

print("The description:", end=" ")

print(func.description)

print('The name: ', end=' ')

print(func.__name__)

print('The class:', end=' ')

print(func.__class__)

print("Now I'll call the function passed in")

func()

another_func(my_func)

another_func(second_func)В приведенном выше коде мы можем передать две разные функции в качестве аргумента в нашу третью функцию и получить разные выходные данные для каждой из них -

The description: A silly function

The name: my_func

The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in My function was called The description: One more sillier function The name: second_func The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in Second function was called

callable objects

Just as functions are objects that can have attributes set on them, it is possible to create an object that can be called as though it were a function.

In Python any object with a __call__() method can be called using function-call syntax.

Inheritance and Polymorphism

Inheritance and polymorphism – this is a very important concept in Python. You must understand it better if you want to learn.

Inheritance

One of the major advantages of Object Oriented Programming is re-use. Inheritance is one of the mechanisms to achieve the same. Inheritance allows programmer to create a general or a base class first and then later extend it to more specialized class. It allows programmer to write better code.

Using inheritance you can use or inherit all the data fields and methods available in your base class. Later you can add you own methods and data fields, thus inheritance provides a way to organize code, rather than rewriting it from scratch.

In object-oriented terminology when class X extend class Y, then Y is called super/parent/base class and X is called subclass/child/derived class. One point to note here is that only data fields and method which are not private are accessible by child classes. Private data fields and methods are accessible only inside the class.

syntax to create a derived class is −

class BaseClass:

Body of base class

class DerivedClass(BaseClass):

Body of derived class

Inheriting Attributes

Now look at the below example −

Output

We first created a class called Date and pass the object as an argument, here-object is built-in class provided by Python. Later we created another class called time and called the Date class as an argument. Through this call we get access to all the data and attributes of Date class into the Time class. Because of that when we try to get the get_date method from the Time class object tm we created earlier possible.

Object.Attribute Lookup Hierarchy

- The instance

- The class

- Any class from which this class inherits

Inheritance Examples

Let’s take a closure look into the inheritance example −

Let’s create couple of classes to participate in examples −

- Animal − Class simulate an animal

- Cat − Subclass of Animal

- Dog − Subclass of Animal

In Python, constructor of class used to create an object (instance), and assign the value for the attributes.

Constructor of subclasses always called to a constructor of parent class to initialize value for the attributes in the parent class, then it start assign value for its attributes.

Output

In the above example, we see the command attributes or methods we put in the parent class so that all subclasses or child classes will inherits that property from the parent class.

If a subclass try to inherits methods or data from another subclass then it will through an error as we see when Dog class try to call swatstring() methods from that cat class, it throws an error(like AttributeError in our case).

Polymorphism (“MANY SHAPES”)

Polymorphism is an important feature of class definition in Python that is utilized when you have commonly named methods across classes or subclasses. This permits functions to use entities of different types at different times. So, it provides flexibility and loose coupling so that code can be extended and easily maintained over time.

This allows functions to use objects of any of these polymorphic classes without needing to be aware of distinctions across the classes.

Polymorphism can be carried out through inheritance, with subclasses making use of base class methods or overriding them.

Let understand the concept of polymorphism with our previous inheritance example and add one common method called show_affection in both subclasses −

From the example we can see, it refers to a design in which object of dissimilar type can be treated in the same manner or more specifically two or more classes with method of the same name or common interface because same method(show_affection in below example) is called with either type of objects.

Output

So, all animals show affections (show_affection), but they do differently. The “show_affection” behaviors is thus polymorphic in the sense that it acted differently depending on the animal. So, the abstract “animal” concept does not actually “show_affection”, but specific animals(like dogs and cats) have a concrete implementation of the action “show_affection”.

Python itself have classes that are polymorphic. Example, the len() function can be used with multiple objects and all return the correct output based on the input parameter.

Overriding

In Python, when a subclass contains a method that overrides a method of the superclass, you can also call the superclass method by calling

Super(Subclass, self).method instead of self.method.

Example

class Thought(object):

def __init__(self):

pass

def message(self):

print("Thought, always come and go")

class Advice(Thought):

def __init__(self):

super(Advice, self).__init__()

def message(self):

print('Warning: Risk is always involved when you are dealing with market!')

Inheriting the Constructor

If we see from our previous inheritance example, __init__ was located in the parent class in the up ‘cause the child class dog or cat didn’t‘ve __init__ method in it. Python used the inheritance attribute lookup to find __init__ in animal class. When we created the child class, first it will look the __init__ method in the dog class, then it didn’t find it then looked into parent class Animal and found there and called that there. So as our class design became complex we may wish to initialize a instance firstly processing it through parent class constructor and then through child class constructor.

Output

In above example- all animals have a name and all dogs a particular breed. We called parent class constructor with super. So dog has its own __init__ but the first thing that happen is we call super. Super is built in function and it is designed to relate a class to its super class or its parent class.

In this case we saying that get the super class of dog and pass the dog instance to whatever method we say here the constructor __init__. So in another words we are calling parent class Animal __init__ with the dog object. You may ask why we won’t just say Animal __init__ with the dog instance, we could do this but if the name of animal class were to change, sometime in the future. What if we wanna rearrange the class hierarchy,so the dog inherited from another class. Using super in this case allows us to keep things modular and easy to change and maintain.

So in this example we are able to combine general __init__ functionality with more specific functionality. This gives us opportunity to separate common functionality from the specific functionality which can eliminate code duplication and relate class to one another in a way that reflects the system overall design.

Conclusion

__init__ is like any other method; it can be inherited

If a class does not have a __init__ constructor, Python will check its parent class to see if it can find one.

As soon as it finds one, Python calls it and stops looking

We can use the super () function to call methods in the parent class.

We may want to initialize in the parent as well as our own class.

Multiple Inheritance and the Lookup Tree

As its name indicates, multiple inheritance is Python is when a class inherits from multiple classes.

For example, a child inherits personality traits from both parents (Mother and Father).

Python Multiple Inheritance Syntax

To make a class inherits from multiple parents classes, we write the the names of these classes inside the parentheses to the derived class while defining it. We separate these names with comma.

Below is an example of that −

>>> class Mother:

pass

>>> class Father:

pass

>>> class Child(Mother, Father):

pass

>>> issubclass(Child, Mother) and issubclass(Child, Father)

True

Multiple inheritance refers to the ability of inheriting from two or more than two class. The complexity arises as child inherits from parent and parents inherits from the grandparent class. Python climbs an inheriting tree looking for attributes that is being requested to be read from an object. It will check the in the instance, within class then parent class and lastly from the grandparent class. Now the question arises in what order the classes will be searched - breath-first or depth-first. By default, Python goes with the depth-first.

That’s is why in the below diagram the Python searches the dothis() method first in class A. So the method resolution order in the below example will be

Mro- D→B→A→C

Look at the below multiple inheritance diagram −

Let’s go through an example to understand the “mro” feature of an Python.

Output

Example 3

Let’s take another example of “diamond shape” multiple inheritance.

Above diagram will be considered ambiguous. From our previous example understanding “method resolution order” .i.e. mro will be D→B→A→C→A but it’s not. On getting the second A from the C, Python will ignore the previous A. so the mro will be in this case will be D→B→C→A.

Let’s create an example based on above diagram −

Output

Simple rule to understand the above output is- if the same class appear in the method resolution order, the earlier appearances of this class will be remove from the method resolution order.

In conclusion −

Any class can inherit from multiple classes

Python normally uses a “depth-first” order when searching inheriting classes.

But when two classes inherit from the same class, Python eliminates the first appearances of that class from the mro.

Decorators, Static and Class Methods

Functions(or methods) are created by def statement.

Though methods works in exactly the same way as a function except one point where method first argument is instance object.

We can classify methods based on how they behave, like

Simple method − defined outside of a class. This function can access class attributes by feeding instance argument:

def outside_func(():

Instance method −

def func(self,)

Class method − if we need to use class attributes

@classmethod

def cfunc(cls,)

Static method − do not have any info about the class

@staticmethod

def sfoo()

Till now we have seen the instance method, now is the time to get some insight into the other two methods,

Class Method

The @classmethod decorator, is a builtin function decorator that gets passed the class it was called on or the class of the instance it was called on as first argument. The result of that evaluation shadows your function definition.

syntax

class C(object):

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

....

fun: function that needs to be converted into a class method

returns: a class method for function

They have the access to this cls argument, it can’t modify object instance state. That would require access to self.

It is bound to the class and not the object of the class.

Class methods can still modify class state that applies across all instances of the class.

Static Method

A static method takes neither a self nor a cls(class) parameter but it’s free to accept an arbitrary number of other parameters.

syntax

class C(object):

@staticmethod

def fun(arg1, arg2, ...):

...

returns: a static method for function funself.

- A static method can neither modify object state nor class state.

- They are restricted in what data they can access.

When to use what

We generally use class method to create factory methods. Factory methods return class object (similar to a constructor) for different use cases.

We generally use static methods to create utility functions.

Python Design Pattern

Overview

Modern software development needs to address complex business requirements. It also needs to take into account factors such as future extensibility and maintainability. A good design of a software system is vital to accomplish these goals. Design patterns play an important role in such systems.

To understand design pattern, let’s consider below example −

Every car’s design follows a basic design pattern, four wheels, steering wheel, the core drive system like accelerator-break-clutch, etc.

So, all things repeatedly built/ produced, shall inevitably follow a pattern in its design.. it cars, bicycle, pizza, atm machines, whatever…even your sofa bed.

Designs that have almost become standard way of coding some logic/mechanism/technique in software, hence come to be known as or studied as, Software Design Patterns.

Why is Design Pattern Important?

Benefits of using Design Patterns are −

Helps you to solve common design problems through a proven approach.

No ambiguity in the understanding as they are well documented.

Reduce the overall development time.

Helps you deal with future extensions and modifications with more ease than otherwise.

May reduce errors in the system since they are proven solutions to common problems.

Classification of Design Patterns

The GoF (Gang of Four) design patterns are classified into three categories namely creational, structural and behavioral.

Creational Patterns

Creational design patterns separate the object creation logic from the rest of the system. Instead of you creating objects, creational patterns creates them for you. The creational patterns include Abstract Factory, Builder, Factory Method, Prototype and Singleton.

Creational Patterns are not commonly used in Python because of the dynamic nature of the language. Also language itself provide us with all the flexibility we need to create in a sufficient elegant fashion, we rarely need to implement anything on top, like singleton or Factory.

Also these patterns provide a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using a new operator.

Structural Patterns

Sometimes instead of starting from scratch, you need to build larger structures by using an existing set of classes. That’s where structural class patterns use inheritance to build a new structure. Structural object patterns use composition/ aggregation to obtain a new functionality. Adapter, Bridge, Composite, Decorator, Façade, Flyweight and Proxy are Structural Patterns. They offers best ways to organize class hierarchy.

Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral patterns offers best ways of handling communication between objects. Patterns comes under this categories are: Visitor, Chain of responsibility, Command, Interpreter, Iterator, Mediator, Memento, Observer, State, Strategy and Template method are Behavioral Patterns.

Because they represent the behavior of a system, they are used generally to describe the functionality of software systems.

Commonly used Design Patterns

Singleton

It is one of the most controversial and famous of all design patterns. It is used in overly object-oriented languages, and is a vital part of traditional object-oriented programming.

The Singleton pattern is used for,

When logging needs to be implemented. The logger instance is shared by all the components of the system.

The configuration files is using this because cache of information needs to be maintained and shared by all the various components in the system.

Managing a connection to a database.

Here is the UML diagram,

class Logger(object):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if not hasattr(cls, '_logger'):

cls._logger = super(Logger, cls).__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs)

return cls._logger

In this example, Logger is a Singleton.

When __new__ is called, it normally constructs a new instance of that class. When we override it, we first check if our singleton instance has been created or not. If not, we create it using a super call. Thus, whenever we call the constructor on Logger, we always get the exact same instance.

>>>

>>> obj1 = Logger()

>>> obj2 = Logger()

>>> obj1 == obj2

True

>>>

>>> obj1

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

>>> obj2

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

Object Oriented Python - Advanced Features

In this we will look into some of the advanced features which Python provide

Core Syntax in our Class design

In this we will look onto, how Python allows us to take advantage of operators in our classes. Python is largely objects and methods call on objects and this even goes on even when its hidden by some convenient syntax.

>>> var1 = 'Hello'

>>> var2 = ' World!'

>>> var1 + var2

'Hello World!'

>>>

>>> var1.__add__(var2)

'Hello World!'

>>> num1 = 45

>>> num2 = 60

>>> num1.__add__(num2)

105

>>> var3 = ['a', 'b']

>>> var4 = ['hello', ' John']

>>> var3.__add__(var4)

['a', 'b', 'hello', ' John']

So if we have to add magic method __add__ to our own classes, could we do that too. Let’s try to do that.

We have a class called Sumlist which has a contructor __init__ which takes list as an argument called my_list.

class SumList(object):

def __init__(self, my_list):

self.mylist = my_list

def __add__(self, other):

new_list = [ x + y for x, y in zip(self.mylist, other.mylist)]

return SumList(new_list)

def __repr__(self):

return str(self.mylist)

aa = SumList([3,6, 9, 12, 15])

bb = SumList([100, 200, 300, 400, 500])

cc = aa + bb # aa.__add__(bb)

print(cc) # should gives us a list ([103, 206, 309, 412, 515])

Output

[103, 206, 309, 412, 515]

But there are many methods which are internally managed by others magic methods. Below are some of them,

'abc' in var # var.__contains__('abc')

var == 'abc' # var.__eq__('abc')

var[1] # var.__getitem__(1)

var[1:3] # var.__getslice__(1, 3)

len(var) # var.__len__()

print(var) # var.__repr__()

Inheriting From built-in types

Classes can also inherit from built-in types this means inherits from any built-in and take advantage of all the functionality found there.

In below example we are inheriting from dictionary but then we are implementing one of its method __setitem__. This (setitem) is invoked when we set key and value in the dictionary. As this is a magic method, this will be called implicitly.

class MyDict(dict):

def __setitem__(self, key, val):

print('setting a key and value!')

dict.__setitem__(self, key, val)

dd = MyDict()

dd['a'] = 10

dd['b'] = 20

for key in dd.keys():

print('{0} = {1}'.format(key, dd[key]))

Output

setting a key and value!

setting a key and value!

a = 10

b = 20

Let’s extend our previous example, below we have called two magic methods called __getitem__ and __setitem__ better invoked when we deal with list index.

# Mylist inherits from 'list' object but indexes from 1 instead for 0!

class Mylist(list): # inherits from list

def __getitem__(self, index):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

return list.__getitem__(self, index) # this method is called when

# we access a value with subscript like x[1]

def __setitem__(self, index, value):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

list.__setitem__(self, index, value)

x = Mylist(['a', 'b', 'c']) # __init__() inherited from builtin list

print(x) # __repr__() inherited from builtin list

x.append('HELLO'); # append() inherited from builtin list

print(x[1]) # 'a' (Mylist.__getitem__ cutomizes list superclass

# method. index is 1, but reflects 0!

print (x[4]) # 'HELLO' (index is 4 but reflects 3!

Output

['a', 'b', 'c']

a

HELLO

In above example, we set a three item list in Mylist and implicitly __init__ method is called and when we print the element x, we get the three item list ([‘a’,’b’,’c’]). Then we append another element to this list. Later we ask for index 1 and index 4. But if you see the output, we are getting element from the (index-1) what we have asked for. As we know list indexing start from 0 but here the indexing start from 1 (that’s why we are getting the first item of the list).

Naming Conventions

In this we will look into names we’ll used for variables especially private variables and conventions used by Python programmers worldwide. Although variables are designated as private but there is not privacy in Python and this by design. Like any other well documented languages, Python has naming and style conventions that it promote although it doesn’t enforce them. There is a style guide written by “Guido van Rossum” the originator of Python, that describe the best practices and use of name and is called PEP8. Here is the link for this, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/

PEP stands for Python enhancement proposal and is a series of documentation that distributed among the Python community to discuss proposed changes. For example it is recommended all,

- Module names − all_lower_case

- Class names and exception names − CamelCase

- Global and local names − all_lower_case

- Functions and method names − all_lower_case

- Constants − ALL_UPPER_CASE

These are just the recommendation, you can vary if you like. But as most of the developers follows these recommendation so might me your code is less readable.

Why conform to convention?