Python hướng đối tượng - Hướng dẫn nhanh

Các ngôn ngữ lập trình đang xuất hiện liên tục và các phương pháp luận khác nhau cũng vậy. Lập trình hướng đối tượng là một trong những phương pháp luận đã trở nên khá phổ biến trong vài năm qua.

Chương này nói về các tính năng của ngôn ngữ lập trình Python khiến nó trở thành ngôn ngữ lập trình hướng đối tượng.

Lược đồ phân loại lập trình ngôn ngữ

Python có thể được mô tả theo phương pháp lập trình hướng đối tượng. Hình ảnh sau đây cho thấy các đặc điểm của các ngôn ngữ lập trình khác nhau. Quan sát các tính năng của Python làm cho nó hướng đối tượng.

| Các lớp Langauage | Thể loại | Langauages |

|---|---|---|

| Mô hình lập trình | Thủ tục | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go |

| Viết kịch bản | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby | |

| Chức năng | Clojure, Eralang, Haskell, Scala | |

| Lớp tổng hợp | Tĩnh | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go, Haskell, Scala |

| Động | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang | |

| Loại lớp | Mạnh | C #, java, Go, Python, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang, Haskell, Scala |

| Yếu | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Perl, Php | |

| Lớp bộ nhớ | Được quản lý | Khác |

| Không được quản lý | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C |

Lập trình hướng đối tượng là gì?

Object Orientednghĩa là hướng về các đối tượng. Nói cách khác, nó có nghĩa là hướng về mặt chức năng đối với các đối tượng mô hình hóa. Đây là một trong nhiều kỹ thuật được sử dụng để mô hình hóa các hệ thống phức tạp bằng cách mô tả một tập hợp các đối tượng tương tác thông qua dữ liệu và hành vi của chúng.

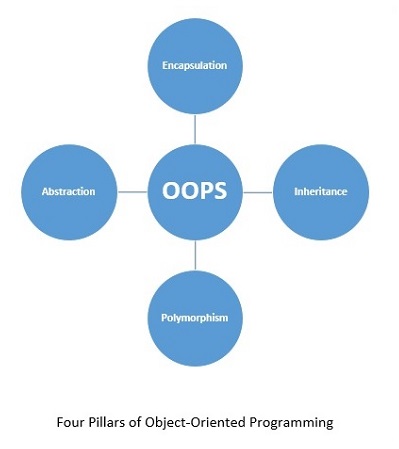

Python, một lập trình hướng đối tượng (OOP), là một cách lập trình tập trung vào việc sử dụng các đối tượng và lớp để thiết kế và xây dựng ứng dụng. Các trụ cột chính của Lập trình hướng đối tượng (OOP) là Inheritance, Polymorphism, Abstraction, quảng cáo Encapsulation.

Phân tích hướng đối tượng (OOA) là quá trình xem xét một vấn đề, hệ thống hoặc nhiệm vụ và xác định các đối tượng và tương tác giữa chúng.

Tại sao nên chọn Lập trình hướng đối tượng?

Python được thiết kế với cách tiếp cận hướng đối tượng. OOP cung cấp những ưu điểm sau:

Cung cấp cấu trúc chương trình rõ ràng, giúp dễ dàng lập bản đồ các vấn đề trong thế giới thực và giải pháp của chúng.

Tạo điều kiện cho việc bảo trì và sửa đổi mã hiện có dễ dàng.

Nâng cao tính mô đun của chương trình vì mỗi đối tượng tồn tại độc lập và các tính năng mới có thể được thêm vào dễ dàng mà không làm ảnh hưởng đến các đối tượng hiện có.

Trình bày một khuôn khổ tốt cho các thư viện mã trong đó các thành phần được cung cấp có thể dễ dàng điều chỉnh và sửa đổi bởi lập trình viên.

Cung cấp khả năng tái sử dụng mã

Lập trình hướng đối tượng so với thủ tục

Lập trình dựa trên thủ tục có nguồn gốc từ lập trình cấu trúc dựa trên các khái niệm functions/procedure/routines. Dễ dàng truy cập và thay đổi dữ liệu trong lập trình hướng thủ tục. Mặt khác, Lập trình hướng đối tượng (OOP) cho phép phân rã một vấn đề thành một số đơn vị được gọi làobjectsvà sau đó xây dựng dữ liệu và chức năng xung quanh các đối tượng này. Nó nhấn mạnh nhiều vào dữ liệu hơn là thủ tục hoặc hàm. Cũng trong OOP, dữ liệu bị ẩn và không thể truy cập bằng thủ tục bên ngoài.

Bảng trong hình ảnh sau đây cho thấy sự khác biệt chính giữa phương pháp tiếp cận POP và OOP.

Sự khác biệt giữa Lập trình hướng thủ tục (POP) vs. Lập trình hướng đối tượng (OOP).

| Lập trình hướng thủ tục | Lập trình hướng đối tượng | |

|---|---|---|

| Dựa trên | Trong Pop, toàn bộ trọng tâm là dữ liệu và chức năng | Oops dựa trên một kịch bản thế giới thực. Chương trình lỗ hổng được chia thành các phần nhỏ gọi là đối tượng |

| Khả năng tái sử dụng | Sử dụng lại mã giới hạn | Sử dụng lại mã |

| Tiếp cận | Phương pháp tiếp cận từ trên xuống | Thiết kế tập trung vào đối tượng |

| Truy cập thông số kỹ thuật | Không có | Công khai, riêng tư và được bảo vệ |

| Di chuyển dữ liệu | Dữ liệu có thể di chuyển tự do từ các chức năng này sang chức năng khác trong hệ thống | Trong Oops, dữ liệu có thể di chuyển và giao tiếp với nhau thông qua các hàm thành viên |

| Truy cập dữ liệu | Trong pop, hầu hết các chức năng sử dụng dữ liệu chung để chia sẻ có thể được truy cập tự do từ chức năng này sang chức năng khác trong hệ thống | Trong Oops, dữ liệu không thể di chuyển tự do từ phương thức này sang phương thức khác, nó có thể được giữ ở chế độ công khai hoặc riêng tư để chúng tôi có thể kiểm soát việc truy cập dữ liệu |

| Ẩn dữ liệu | Trong cửa sổ bật lên, cách cụ thể để ẩn dữ liệu, nên kém an toàn hơn một chút | Nó cung cấp tính năng ẩn dữ liệu, an toàn hơn nhiều |

| Quá tải | Không thể | Chức năng và Người vận hành quá tải |

| Ví dụ-Ngôn ngữ | C, VB, Fortran, Pascal | C ++, Python, Java, C # |

| Trừu tượng | Sử dụng trừu tượng ở cấp thủ tục | Sử dụng tính trừu tượng ở cấp độ lớp và đối tượng |

Nguyên tắc lập trình hướng đối tượng

Lập trình hướng đối tượng (OOP) dựa trên khái niệm objects hơn là hành động, và datahơn là logic. Để một ngôn ngữ lập trình hướng đối tượng, nó cần có một cơ chế cho phép làm việc với các lớp và đối tượng cũng như việc triển khai và sử dụng các nguyên tắc và khái niệm hướng đối tượng cơ bản như kế thừa, trừu tượng, đóng gói và đa hình.

Hãy để chúng tôi hiểu ngắn gọn từng trụ cột của lập trình hướng đối tượng -

Đóng gói

Thuộc tính này ẩn các chi tiết không cần thiết và giúp quản lý cấu trúc chương trình dễ dàng hơn. Việc triển khai và trạng thái của mỗi đối tượng được ẩn sau các ranh giới được xác định rõ ràng và cung cấp một giao diện đơn giản và gọn gàng để làm việc với chúng. Một cách để thực hiện điều này là đặt dữ liệu ở chế độ riêng tư.

Di sản

Kế thừa, còn được gọi là tổng quát hóa, cho phép chúng ta nắm bắt được mối quan hệ phân cấp giữa các lớp và đối tượng. Ví dụ, một 'trái cây' là sự khái quát của 'quả cam'. Kế thừa rất hữu ích từ góc độ tái sử dụng mã.

Trừu tượng

Thuộc tính này cho phép chúng ta ẩn các chi tiết và chỉ hiển thị các tính năng cần thiết của một khái niệm hoặc đối tượng. Ví dụ, một người lái xe tay ga biết rằng khi nhấn còi, âm thanh sẽ phát ra, nhưng anh ta không biết âm thanh thực sự được tạo ra như thế nào khi nhấn còi.

Đa hình

Đa hình có nghĩa là nhiều dạng. Có nghĩa là, một sự vật hoặc hành động hiện diện dưới những hình thức hoặc cách thức khác nhau. Một ví dụ điển hình về tính đa hình là nạp chồng hàm tạo trong các lớp.

Python hướng đối tượng

Trung tâm của lập trình Python là object và OOP, tuy nhiên, bạn không cần hạn chế sử dụng OOP bằng cách tổ chức mã của bạn thành các lớp. OOP bổ sung vào toàn bộ triết lý thiết kế của Python và khuyến khích một cách lập trình sạch sẽ và thực dụng. OOP cũng cho phép viết các chương trình lớn hơn và phức tạp.

Mô-đun so với Lớp và Đối tượng

Mô-đun giống như "Từ điển"

Khi làm việc trên Mô-đun, hãy lưu ý những điểm sau:

Mô-đun Python là một gói để đóng gói mã có thể sử dụng lại.

Các mô-đun nằm trong một thư mục có __init__.py tập tin trên đó.

Mô-đun chứa các hàm và lớp.

Các mô-đun được nhập bằng cách sử dụng import từ khóa.

Nhớ lại rằng từ điển là một key-valueđôi. Điều đó có nghĩa là nếu bạn có một từ điển có khóaEmployeID và bạn muốn truy xuất nó, thì bạn sẽ phải sử dụng các dòng mã sau:

employee = {“EmployeID”: “Employee Unique Identity!”}

print (employee [‘EmployeID])Bạn sẽ phải làm việc trên các mô-đun với quy trình sau:

Mô-đun là một tệp Python với một số hàm hoặc biến trong đó.

Nhập tệp bạn cần.

Bây giờ, bạn có thể truy cập các hàm hoặc biến trong mô-đun đó bằng dấu '.' (dot) Nhà điều hành.

Hãy xem xét một mô-đun có tên employee.py với một chức năng trong nó được gọi là employee. Mã của hàm được đưa ra dưới đây:

# this goes in employee.py

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)Bây giờ nhập mô-đun và sau đó truy cập chức năng EmployeID -

import employee

employee. EmployeID()Bạn có thể chèn một biến có tên là Age, như hình -

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)

# just a variable

Age = “Employee age is **”Bây giờ, truy cập biến đó theo cách sau:

import employee

employee.EmployeID()

print(employee.Age)Bây giờ, hãy so sánh điều này với từ điển -

Employee[‘EmployeID’] # get EmployeID from employee

Employee.employeID() # get employeID from the module

Employee.Age # get access to variableLưu ý rằng có một mẫu phổ biến trong Python:

Đi một key = value hộp đựng phong cách

Lấy một cái gì đó ra khỏi nó bằng tên của khóa

Khi so sánh mô-đun với từ điển, cả hai đều tương tự nhau, ngoại trừ những điều sau:

Trong trường hợp của dictionary, khóa là một chuỗi và cú pháp là [key].

Trong trường hợp của module, khóa là số nhận dạng và cú pháp là .key.

Các lớp học giống như Mô-đun

Mô-đun là một từ điển chuyên dụng có thể lưu trữ mã Python để bạn có thể truy cập nó bằng dấu '.' Nhà điều hành. Lớp là một cách để lấy một nhóm các chức năng và dữ liệu và đặt chúng bên trong một vùng chứa để bạn có thể truy cập chúng bằng bộ điều hành '.'.

Nếu bạn phải tạo một lớp tương tự như mô-đun nhân viên, bạn có thể thực hiện bằng cách sử dụng mã sau:

class employee(object):

def __init__(self):

self. Age = “Employee Age is ##”

def EmployeID(self):

print (“This is just employee unique identity”)Note- Các lớp học được ưu tiên hơn các mô-đun vì bạn có thể sử dụng lại chúng như cũ và không bị can thiệp nhiều. Trong khi với các mô-đun, bạn chỉ có một với toàn bộ chương trình.

Đối tượng giống như Nhập khẩu nhỏ

Một lớp học giống như một mini-module và bạn có thể nhập theo cách tương tự như cách bạn làm đối với các lớp, sử dụng khái niệm được gọi là instantiate. Lưu ý rằng khi bạn khởi tạo một lớp, bạn sẽ nhận đượcobject.

Bạn có thể khởi tạo một đối tượng, tương tự như việc gọi một lớp như một hàm, như minh họa:

this_obj = employee() # Instantiatethis_obj.EmployeID() # get EmployeId from the class

print(this_obj.Age) # get variable AgeBạn có thể thực hiện việc này bằng bất kỳ cách nào trong ba cách sau:

# dictionary style

Employee[‘EmployeID’]

# module style

Employee.EmployeID()

Print(employee.Age)

# Class style

this_obj = employee()

this_obj.employeID()

Print(this_obj.Age)Chương này sẽ giải thích chi tiết về cách thiết lập môi trường Python trên máy tính cục bộ của bạn.

Điều kiện tiên quyết và Bộ công cụ

Trước khi bạn tiếp tục tìm hiểu thêm về Python, chúng tôi khuyên bạn nên kiểm tra xem các điều kiện tiên quyết sau có được đáp ứng hay không:

Phiên bản Python mới nhất được cài đặt trên máy tính của bạn

IDE hoặc trình soạn thảo văn bản đã được cài đặt

Bạn có kiến thức cơ bản để viết và gỡ lỗi bằng Python, tức là bạn có thể thực hiện những việc sau trong Python:

Có khả năng viết và chạy các chương trình Python.

Gỡ lỗi chương trình và chẩn đoán lỗi.

Làm việc với các kiểu dữ liệu cơ bản.

Viết for vòng lặp, while vòng lặp, và if các câu lệnh

Mã functions

Nếu bạn chưa có bất kỳ kinh nghiệm nào về ngôn ngữ lập trình, bạn có thể tìm thấy rất nhiều hướng dẫn dành cho người mới bắt đầu bằng Python trên

https://www.tutorialpoints.com/Cài đặt Python

Các bước sau đây chỉ cho bạn chi tiết cách cài đặt Python trên máy tính cục bộ của bạn -

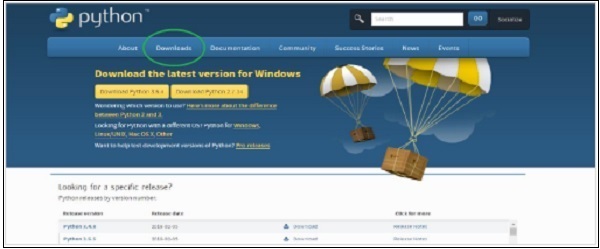

Step 1 - Truy cập trang web Python chính thức https://www.python.org/, nhấp vào Downloads và chọn phiên bản mới nhất hoặc bất kỳ phiên bản ổn định nào bạn chọn.

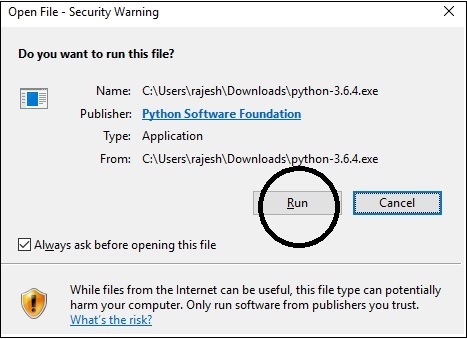

Step 2- Lưu tệp exe của trình cài đặt Python mà bạn đang tải xuống và khi bạn đã tải xuống, hãy mở tệp đó. Bấm vàoRun và lựa chọn Next theo mặc định và kết thúc cài đặt.

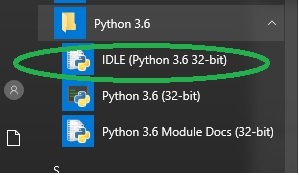

Step 3- Sau khi cài đặt xong, bây giờ bạn sẽ thấy menu Python như trong hình bên dưới. Khởi động chương trình bằng cách chọn IDLE (Python GUI).

Điều này sẽ bắt đầu trình bao Python. Nhập các lệnh đơn giản để kiểm tra cài đặt.

Chọn một IDE

Môi trường phát triển tích hợp là một trình soạn thảo văn bản hướng tới phát triển phần mềm. Bạn sẽ phải cài đặt IDE để kiểm soát luồng lập trình của mình và nhóm các dự án lại với nhau khi làm việc trên Python. Dưới đây là một số IDE có sẵn trực tuyến. Bạn có thể chọn một trong những thuận tiện của bạn.

- Pycharm IDE

- Komodo IDE

- Eric Python IDE

Note - Eclipse IDE chủ yếu được sử dụng trong Java, tuy nhiên nó có một plugin Python.

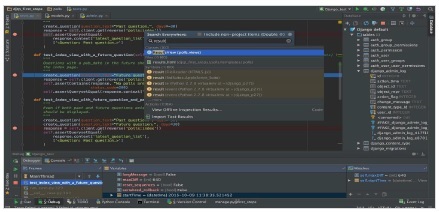

Pycharm

Pycharm, IDE đa nền tảng là một trong những IDE phổ biến nhất hiện có. Nó cung cấp hỗ trợ mã hóa và phân tích với việc hoàn thành mã, điều hướng dự án và mã, kiểm tra đơn vị tích hợp, tích hợp kiểm soát phiên bản, gỡ lỗi và hơn thế nữa

Liên kết tải xuống

https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/download/#section=windowsLanguages Supported - Python, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Coffee Script, TypeScript, Cython, AngularJS, Node.js, các ngôn ngữ mẫu.

Ảnh chụp màn hình

Tại sao chọn?

PyCharm cung cấp các tính năng và lợi ích sau cho người dùng:

- IDE đa nền tảng tương thích với Windows, Linux và Mac OS

- Bao gồm Django IDE, cộng với hỗ trợ CSS và JavaScript

- Bao gồm hàng nghìn plugin, thiết bị đầu cuối tích hợp và kiểm soát phiên bản

- Tích hợp với Git, SVN và Mercurial

- Cung cấp các công cụ chỉnh sửa thông minh cho Python

- Tích hợp dễ dàng với Virtualenv, Docker và Vagrant

- Các tính năng điều hướng và tìm kiếm đơn giản

- Phân tích và tái cấu trúc mã

- Tiêm có thể cấu hình

- Hỗ trợ hàng tấn thư viện Python

- Chứa các Mẫu và trình gỡ lỗi JavaScript

- Bao gồm trình gỡ lỗi Python / Django

- Hoạt động với Google App Engine, các khung và thư viện bổ sung.

- Có giao diện người dùng có thể tùy chỉnh, mô phỏng VIM có sẵn

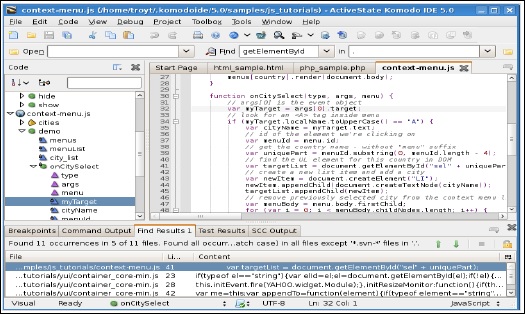

Komodo IDE

Nó là một IDE đa ô hỗ trợ hơn 100 ngôn ngữ và về cơ bản cho các ngôn ngữ động như Python, PHP và Ruby. Nó là một IDE thương mại có sẵn để dùng thử miễn phí trong 21 ngày với đầy đủ chức năng. ActiveState là công ty phần mềm quản lý sự phát triển của IDE Komodo. Nó cũng cung cấp một phiên bản rút gọn của Komodo được gọi là Komodo Edit cho các tác vụ lập trình đơn giản.

IDE này chứa tất cả các loại tính năng từ cơ bản đến nâng cao. Nếu bạn là sinh viên hoặc người làm nghề tự do, thì bạn có thể mua nó gần một nửa so với giá thực tế. Tuy nhiên, nó hoàn toàn miễn phí cho các giáo viên và giáo sư từ các tổ chức và trường đại học được công nhận.

Nó có tất cả các tính năng bạn cần để phát triển web và di động, bao gồm hỗ trợ cho tất cả các ngôn ngữ và khuôn khổ của bạn.

Liên kết tải xuống

Các liên kết tải xuống cho Komodo Edit (phiên bản miễn phí) và Komodo IDE (phiên bản trả phí) được cung cấp tại đây -

Komodo Edit (free)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-editKomodo IDE (paid)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-ide/downloads/ideẢnh chụp màn hình

Tại sao chọn?

- IDE mạnh mẽ với hỗ trợ Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby và nhiều hơn nữa.

- IDE đa nền tảng.

Nó bao gồm các tính năng cơ bản như hỗ trợ trình gỡ lỗi tích hợp, tự động hoàn thành, trình xem Mô hình đối tượng tài liệu (DOM), trình duyệt mã, trình bao tương tác, cấu hình điểm ngắt, cấu hình mã, kiểm tra đơn vị tích hợp. Nói tóm lại, nó là một IDE chuyên nghiệp với một loạt các tính năng thúc đẩy năng suất.

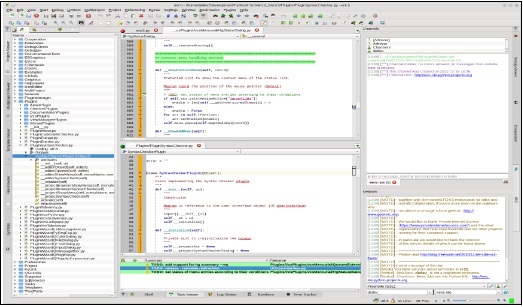

Eric Python IDE

Nó là một IDE mã nguồn mở cho Python và Ruby. Eric là một trình soạn thảo và IDE đầy đủ tính năng, được viết bằng Python. Nó dựa trên bộ công cụ Qt GUI đa nền tảng, tích hợp điều khiển trình soạn thảo Scintilla rất linh hoạt. IDE có rất nhiều cấu hình và người ta có thể chọn những gì để sử dụng và những gì không. Bạn có thể tải xuống Eric IDE từ liên kết dưới đây:

https://eric-ide.python-projects.org/eric-download.htmlTại sao chọn

- Thụt lề nhiều, đánh dấu lỗi.

- Hỗ trợ mã

- Hoàn thành mã

- Dọn mã bằng PyLint

- Tìm kiếm nhanh

- Trình gỡ lỗi Python tích hợp.

Ảnh chụp màn hình

Chọn một trình soạn thảo văn bản

Không phải lúc nào bạn cũng cần IDE. Đối với các tác vụ như học viết mã bằng Python hoặc Arduino hoặc khi làm việc trên một tập lệnh nhanh trong tập lệnh shell để giúp bạn tự động hóa một số tác vụ, trình soạn thảo văn bản tập trung vào mã đơn giản và nhẹ sẽ thực hiện. Ngoài ra, nhiều trình soạn thảo văn bản cung cấp các tính năng như tô sáng cú pháp và thực thi tập lệnh trong chương trình, tương tự như IDE. Một số trình soạn thảo văn bản được cung cấp ở đây -

- Atom

- Văn bản tuyệt vời

- Notepad++

Trình soạn thảo văn bản Atom

Atom là một trình soạn thảo văn bản có thể hack được xây dựng bởi nhóm GitHub. Nó là một trình soạn thảo văn bản và mã nguồn mở và miễn phí, có nghĩa là tất cả các mã đều có sẵn để bạn đọc, sửa đổi để sử dụng cho riêng mình và thậm chí đóng góp các cải tiến. Nó là một trình soạn thảo văn bản đa nền tảng tương thích cho macOS, Linux và Microsoft Windows với sự hỗ trợ cho các trình cắm thêm được viết bằng Node.js và Git Control được nhúng.

Liên kết tải xuống

https://atom.io/Ảnh chụp màn hình

Ngôn ngữ được hỗ trợ

C / C ++, C #, CSS, CoffeeScript, HTML, JavaScript, Java, JSON, Julia, Objective-C, PHP, Perl, Python, Ruby on Rails, Ruby, Shell script, Scala, SQL, XML, YAML và nhiều hơn nữa.

Trình chỉnh sửa văn bản siêu phàm

Sublime text là một phần mềm độc quyền và nó cung cấp cho bạn phiên bản dùng thử miễn phí để kiểm tra trước khi mua. Theo stackoverflow.com , đây là Môi trường phát triển phổ biến thứ tư.

Một số lợi thế mà nó cung cấp là tốc độ đáng kinh ngạc, dễ sử dụng và hỗ trợ cộng đồng. Nó cũng hỗ trợ nhiều ngôn ngữ lập trình và ngôn ngữ đánh dấu, và người dùng có thể thêm các chức năng bằng các plugin, thường do cộng đồng xây dựng và duy trì theo giấy phép phần mềm miễn phí.

Ảnh chụp màn hình

Ngôn ngữ được hỗ trợ

- Python, Ruby, JavaScript, v.v.

Tại sao chọn?

Tùy chỉnh các ràng buộc chính, menu, đoạn trích, macro, phần hoàn chỉnh và hơn thế nữa.

Tính năng tự động hoàn thành

- Chèn nhanh Văn bản và mã với các đoạn văn bản siêu phàm bằng cách sử dụng đoạn mã, điểm đánh dấu trường và giá giữ vị trí

Mở cửa nhanh chóng

Hỗ trợ đa nền tảng cho Mac, Linux và Windows.

Chuyển con trỏ đến nơi bạn muốn đến

Chọn Nhiều Dòng, Từ và Cột

Notepad ++

Đó là một trình soạn thảo mã nguồn miễn phí và thay thế Notepad hỗ trợ một số ngôn ngữ từ Assembly đến XML và bao gồm cả Python. Chạy trong môi trường MS windows, việc sử dụng nó được điều chỉnh bởi giấy phép GPL. Ngoài tính năng đánh dấu cú pháp, Notepad ++ có một số tính năng đặc biệt hữu ích cho lập trình viên.

Ảnh chụp màn hình

Các tính năng chính

- Đánh dấu cú pháp và gấp cú pháp

- PCRE (Biểu thức chính quy tương thích Perl) Tìm kiếm / Thay thế

- GUI hoàn toàn có thể tùy chỉnh

- SAU tự động hoàn thành

- Chỉnh sửa theo tab

- Multi-View

- Môi trường đa ngôn ngữ

- Có thể chạy với các đối số khác nhau

Ngôn ngữ được hỗ trợ

- Hầu hết mọi ngôn ngữ (hơn 60 ngôn ngữ) như Python, C, C ++, C #, Java, v.v.

Các cấu trúc dữ liệu Python rất trực quan theo quan điểm cú pháp và chúng cung cấp nhiều lựa chọn hoạt động. Bạn cần chọn cấu trúc dữ liệu Python tùy thuộc vào những gì dữ liệu liên quan, nếu nó cần được sửa đổi hoặc nếu nó là một dữ liệu cố định và loại truy cập nào được yêu cầu, chẳng hạn như ở đầu / cuối / ngẫu nhiên, v.v.

Danh sách

Danh sách đại diện cho kiểu cấu trúc dữ liệu linh hoạt nhất trong Python. Danh sách là một vùng chứa chứa các giá trị được phân tách bằng dấu phẩy (các mục hoặc phần tử) giữa các dấu ngoặc vuông. Danh sách rất hữu ích khi chúng ta muốn làm việc với nhiều giá trị có liên quan. Vì danh sách giữ dữ liệu cùng nhau, chúng ta có thể thực hiện các phương pháp và thao tác giống nhau trên nhiều giá trị cùng một lúc. Các chỉ mục của danh sách bắt đầu từ 0 và không giống như chuỗi, danh sách có thể thay đổi.

Cấu trúc dữ liệu - Danh sách

>>>

>>> # Any Empty List

>>> empty_list = []

>>>

>>> # A list of String

>>> str_list = ['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> # A list of Integers

>>> int_list = [1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>>

>>> #Mixed items list

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>> # To print the list

>>>

>>> print(empty_list)

[]

>>> print(str_list)

['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> print(type(str_list))

<class 'list'>

>>> print(int_list)

[1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>> print(mixed_list)

['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']Truy cập các mục trong danh sách Python

Mỗi mục trong danh sách được gán một số - đó là chỉ mục hoặc vị trí của số đó. Lập chỉ mục luôn bắt đầu từ 0, chỉ mục thứ hai là một, v.v. Để truy cập các mục trong danh sách, chúng ta có thể sử dụng các số chỉ mục này trong dấu ngoặc vuông. Hãy quan sát đoạn mã sau để làm ví dụ:

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>>

>>> # To access the First Item of the list

>>> mixed_list[0]

'This'

>>> # To access the 4th item

>>> mixed_list[3]

18

>>> # To access the last item of the list

>>> mixed_list[-1]

'list'Đối tượng rỗng

Đối tượng rỗng là kiểu tích hợp sẵn trong Python đơn giản và cơ bản nhất. Chúng tôi đã sử dụng chúng nhiều lần mà không nhận thấy và đã mở rộng nó cho mọi lớp chúng tôi đã tạo. Mục đích chính để viết một lớp trống là để chặn một cái gì đó trong thời gian này và sau đó mở rộng và thêm một hành vi vào nó.

Để thêm một hành vi vào một lớp có nghĩa là thay thế một cấu trúc dữ liệu bằng một đối tượng và thay đổi tất cả các tham chiếu đến nó. Vì vậy, điều quan trọng là phải kiểm tra dữ liệu, liệu nó có phải là một đối tượng ngụy trang hay không, trước khi bạn tạo bất cứ thứ gì. Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu rõ hơn:

>>> #Empty objects

>>>

>>> obj = object()

>>> obj.x = 9

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

obj.x = 9

AttributeError: 'object' object has no attribute 'x'Vì vậy, từ phía trên, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng không thể thiết lập bất kỳ thuộc tính nào trên một đối tượng đã được khởi tạo trực tiếp. Khi Python cho phép một đối tượng có các thuộc tính tùy ý, cần một lượng bộ nhớ hệ thống nhất định để theo dõi các thuộc tính mà mỗi đối tượng có, để lưu trữ cả tên thuộc tính và giá trị của nó. Ngay cả khi không có thuộc tính nào được lưu trữ, một lượng bộ nhớ nhất định sẽ được cấp cho các thuộc tính mới tiềm năng.

Vì vậy, theo mặc định, Python sẽ vô hiệu hóa các thuộc tính tùy ý trên đối tượng và một số cài sẵn khác.

>>> # Empty Objects

>>>

>>> class EmpObject:

pass

>>> obj = EmpObject()

>>> obj.x = 'Hello, World!'

>>> obj.x

'Hello, World!'Do đó, nếu chúng ta muốn nhóm các thuộc tính lại với nhau, chúng ta có thể lưu trữ chúng trong một đối tượng trống như được hiển thị trong đoạn mã trên. Tuy nhiên, phương pháp này không phải lúc nào cũng được gợi ý. Hãy nhớ rằng các lớp và đối tượng chỉ nên được sử dụng khi bạn muốn chỉ định cả dữ liệu và hành vi.

Tuples

Tuples tương tự như danh sách và có thể lưu trữ các phần tử. Tuy nhiên, chúng là bất biến, vì vậy chúng ta không thể thêm, bớt hoặc thay thế các đối tượng. Lợi ích chính mà tuple mang lại vì tính bất biến của nó là chúng ta có thể sử dụng chúng làm khóa trong từ điển hoặc ở các vị trí khác nơi một đối tượng yêu cầu giá trị băm.

Tuples được sử dụng để lưu trữ dữ liệu chứ không phải hành vi. Trong trường hợp bạn yêu cầu hành vi để thao tác một tuple, bạn cần truyền tuple vào một hàm (hoặc phương thức trên một đối tượng khác) thực hiện hành động.

Vì tuple có thể hoạt động như một khóa từ điển, các giá trị được lưu trữ là khác nhau. Chúng ta có thể tạo một bộ giá trị bằng cách phân tách các giá trị bằng dấu phẩy. Các bộ giá trị được gói trong ngoặc đơn nhưng không bắt buộc. Đoạn mã sau đây hiển thị hai nhiệm vụ giống hệt nhau.

>>> stock1 = 'MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45

>>> stock2 = ('MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45)

>>> type (stock1)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> type(stock2)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> stock1 == stock2

True

>>>Xác định Tuple

Bộ giá trị rất giống với danh sách ngoại trừ toàn bộ tập hợp các phần tử được đặt trong dấu ngoặc đơn thay vì dấu ngoặc vuông.

Giống như khi bạn cắt một danh sách, bạn sẽ có một danh sách mới và khi bạn cắt một bộ, bạn sẽ có một bộ mới.

>>> tupl = ('Tuple','is', 'an','IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl[0]

'Tuple'

>>> tupl[-1]

'list'

>>> tupl[1:3]

('is', 'an')Phương thức Tuple trong Python

Đoạn mã sau hiển thị các phương thức trong bộ dữ liệu Python:

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl.append('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#148>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.append('new')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

>>> tupl.remove('is')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#149>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.remove('is')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'remove'

>>> tupl.index('list')

4

>>> tupl.index('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#151>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.index('new')

ValueError: tuple.index(x): x not in tuple

>>> "is" in tupl

True

>>> tupl.count('is')

1Từ đoạn mã được hiển thị ở trên, chúng ta có thể hiểu rằng các bộ giá trị là bất biến và do đó -

Bạn cannot thêm các phần tử vào một tuple.

Bạn cannot nối hoặc mở rộng một phương thức.

Bạn cannot loại bỏ các phần tử khỏi một tuple.

Tuples có no loại bỏ hoặc phương thức bật.

Đếm và chỉ mục là các phương thức có sẵn trong một bộ giá trị.

Từ điển

Từ điển là một trong những kiểu dữ liệu tích hợp sẵn của Python và nó xác định mối quan hệ 1-1 giữa các khóa và giá trị.

Định nghĩa từ điển

Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu về cách xác định từ điển -

>>> # empty dictionary

>>> my_dict = {}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with integer keys

>>> my_dict = { 1:'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with mixed keys

>>> my_dict = {'name': 'Aarav', 1: [ 2, 4, 10]}

>>>

>>> # using built-in function dict()

>>> my_dict = dict({1:'msft', 2:'IT'})

>>>

>>> # From sequence having each item as a pair

>>> my_dict = dict([(1,'msft'), (2,'IT')])

>>>

>>> # Accessing elements of a dictionary

>>> my_dict[1]

'msft'

>>> my_dict[2]

'IT'

>>> my_dict['IT']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#177>", line 1, in <module>

my_dict['IT']

KeyError: 'IT'

>>>Từ đoạn mã trên, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng:

Đầu tiên, chúng tôi tạo một từ điển với hai phần tử và gán nó cho biến my_dict. Mỗi phần tử là một cặp khóa-giá trị và toàn bộ tập hợp các phần tử được đặt trong dấu ngoặc nhọn.

Con số 1 là chìa khóa và msftlà giá trị của nó. Tương tự,2 là chìa khóa và IT là giá trị của nó.

Bạn có thể nhận giá trị theo khóa, nhưng không thể ngược lại. Vì vậy, khi chúng tôi cố gắngmy_dict[‘IT’] , nó đưa ra một ngoại lệ, bởi vì IT không phải là một chìa khóa.

Sửa đổi từ điển

Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu về cách sửa đổi từ điển -

>>> # Modifying a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>> my_dict[2] = 'Software'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software'}

>>>

>>> my_dict[3] = 'Microsoft Technologies'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}Từ đoạn mã trên, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng -

Bạn không thể có các khóa trùng lặp trong từ điển. Thay đổi giá trị của khóa hiện có sẽ xóa giá trị cũ.

Bạn có thể thêm các cặp khóa-giá trị mới bất kỳ lúc nào.

Từ điển không có khái niệm về thứ tự giữa các yếu tố. Chúng là những bộ sưu tập đơn giản không có thứ tự.

Trộn các loại dữ liệu trong một từ điển

Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu về cách trộn các kiểu dữ liệu trong từ điển -

>>> # Mixing Data Types in a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}

>>> my_dict[4] = 'Operating System'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>> my_dict['Bill Gates'] = 'Owner'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}Từ đoạn mã trên, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng -

Không chỉ chuỗi mà giá trị từ điển có thể thuộc bất kỳ kiểu dữ liệu nào bao gồm chuỗi, số nguyên, kể cả chính từ điển.

Không giống như giá trị từ điển, khóa từ điển bị hạn chế hơn, nhưng có thể thuộc bất kỳ loại nào như chuỗi, số nguyên hoặc bất kỳ loại nào khác.

Xóa các mục khỏi từ điển

Tuân thủ đoạn mã sau để hiểu về cách xóa các mục khỏi từ điển -

>>> # Deleting Items from a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}

>>>

>>> del my_dict['Bill Gates']

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>>

>>> my_dict.clear()

>>> my_dict

{}Từ đoạn mã trên, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng -

del - cho phép bạn xóa từng mục khỏi từ điển bằng phím.

clear - Xóa tất cả các mục khỏi từ điển.

Bộ

Set () là một tập hợp không có thứ tự không có phần tử trùng lặp. Mặc dù các mục riêng lẻ là không thể thay đổi, nhưng bản thân tập hợp là có thể thay đổi, tức là chúng ta có thể thêm hoặc xóa các phần tử / mục khỏi tập hợp. Chúng ta có thể thực hiện các phép toán như liên hiệp, giao điểm, v.v. với tập hợp.

Mặc dù các tập hợp nói chung có thể được triển khai bằng cách sử dụng cây, nhưng tập hợp trong Python có thể được triển khai bằng cách sử dụng bảng băm. Điều này cho phép nó một phương pháp được tối ưu hóa cao để kiểm tra xem một phần tử cụ thể có được chứa trong tập hợp hay không

Tạo một tập hợp

Một tập hợp được tạo bằng cách đặt tất cả các mục (phần tử) bên trong dấu ngoặc nhọn {}, được phân tách bằng dấu phẩy hoặc bằng cách sử dụng hàm tích hợp set(). Quan sát các dòng mã sau:

>>> #set of integers

>>> my_set = {1,2,4,8}

>>> print(my_set)

{8, 1, 2, 4}

>>>

>>> #set of mixed datatypes

>>> my_set = {1.0, "Hello World!", (2, 4, 6)}

>>> print(my_set)

{1.0, (2, 4, 6), 'Hello World!'}

>>>Phương pháp cho Bộ

Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu về các phương thức dành cho tập hợp -

>>> >>> #METHODS FOR SETS

>>>

>>> #add(x) Method

>>> topics = {'Python', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>> topics.add('C++')

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>>

>>> #union(s) Method, returns a union of two set.

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>> team = {'Developer', 'Content Writer', 'Editor','Tester'}

>>> group = topics.union(team)

>>> group

{'Tester', 'C#', 'Python', 'Editor', 'Developer', 'C++', 'Java', 'Content

Writer'}

>>> # intersets(s) method, returns an intersection of two sets

>>> inters = topics.intersection(team)

>>> inters

set()

>>>

>>> # difference(s) Method, returns a set containing all the elements of

invoking set but not of the second set.

>>>

>>> safe = topics.difference(team)

>>> safe

{'Python', 'C++', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>>

>>> diff = topics.difference(group)

>>> diff

set()

>>> #clear() Method, Empties the whole set.

>>> group.clear()

>>> group

set()

>>>Toán tử cho Bộ

Quan sát đoạn mã sau để hiểu về các toán tử cho các tập hợp -

>>> # PYTHON SET OPERATIONS

>>>

>>> #Creating two sets

>>> set1 = set()

>>> set2 = set()

>>>

>>> # Adding elements to set

>>> for i in range(1,5):

set1.add(i)

>>> for j in range(4,9):

set2.add(j)

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set2

{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Union of set1 and set2

>>> set3 = set1 | set2 # same as set1.union(set2)

>>> print('Union of set1 & set2: set3 = ', set3)

Union of set1 & set2: set3 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Intersection of set1 & set2

>>> set4 = set1 & set2 # same as set1.intersection(set2)

>>> print('Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = ', set4)

Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = {4}

>>>

>>> # Checking relation between set3 and set4

>>> if set3 > set4: # set3.issuperset(set4)

print('Set3 is superset of set4')

elif set3 < set4: #set3.issubset(set4)

print('Set3 is subset of set4')

else: #set3 == set4

print('Set 3 is same as set4')

Set3 is superset of set4

>>>

>>> # Difference between set3 and set4

>>> set5 = set3 - set4

>>> print('Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = ', set5)

Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> # Check if set4 and set5 are disjoint sets

>>> if set4.isdisjoint(set5):

print('Set4 and set5 have nothing in common\n')

Set4 and set5 have nothing in common

>>> # Removing all the values of set5

>>> set5.clear()

>>> set5 set()Trong chương này, chúng ta sẽ thảo luận chi tiết về các thuật ngữ hướng đối tượng và các khái niệm lập trình. Class chỉ là một nhà máy cho một ví dụ. Nhà máy này chứa bản thiết kế mô tả cách tạo các phiên bản. Một cá thể hoặc đối tượng được xây dựng từ lớp. Trong hầu hết các trường hợp, chúng ta có thể có nhiều hơn một trường hợp của một lớp. Mọi cá thể đều có một tập hợp các thuộc tính và các thuộc tính này được định nghĩa trong một lớp, vì vậy mọi cá thể của một lớp cụ thể được mong đợi có các thuộc tính giống nhau.

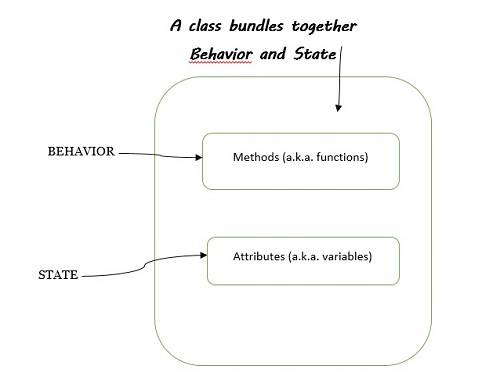

Gói lớp: Hành vi và trạng thái

Một lớp sẽ cho phép bạn nhóm các hành vi và trạng thái của một đối tượng lại với nhau. Quan sát sơ đồ sau để hiểu rõ hơn -

Những điểm sau đây đáng chú ý khi thảo luận về nhóm lớp:

Từ behavior giống hệt với function - nó là một đoạn mã thực hiện điều gì đó (hoặc triển khai một hành vi)

Từ state giống hệt với variables - nó là nơi lưu trữ các giá trị trong một lớp.

Khi chúng ta khẳng định một hành vi và trạng thái của lớp cùng nhau, điều đó có nghĩa là một lớp đóng gói các hàm và biến.

Các lớp có các phương thức và thuộc tính

Trong Python, việc tạo một phương thức xác định một hành vi của lớp. Phương thức từ là tên OOP được đặt cho một hàm được định nghĩa trong một lớp. Tóm lại -

Class functions - là từ đồng nghĩa với methods

Class variables - là từ đồng nghĩa với name attributes.

Class - một bản thiết kế cho một ví dụ có hành vi chính xác.

Object - một trong những thể hiện của lớp, thực hiện chức năng được định nghĩa trong lớp.

Type - chỉ ra lớp mà cá thể thuộc về

Attribute - Bất kỳ giá trị đối tượng nào: object.attribute

Method - một "thuộc tính có thể gọi" được xác định trong lớp

Hãy quan sát đoạn mã sau đây chẳng hạn:

var = “Hello, John”

print( type (var)) # < type ‘str’> or <class 'str'>

print(var.upper()) # upper() method is called, HELLO, JOHNSáng tạo và Thuyết minh

Đoạn mã sau đây cho thấy cách tạo lớp đầu tiên của chúng ta và sau đó là phiên bản của nó.

class MyClass(object):

pass

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj)Ở đây chúng tôi đã tạo một lớp có tên là MyClassvà không làm bất kỳ nhiệm vụ nào. Đối sốobject trong MyClass lớp liên quan đến kế thừa lớp và sẽ được thảo luận trong các chương sau. pass trong đoạn mã trên chỉ ra rằng khối này trống, đó là định nghĩa lớp trống.

Hãy để chúng tôi tạo một phiên bản this_obj của MyClass() lớp và in nó như được hiển thị -

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x03B08E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x0369D390>Ở đây, chúng tôi đã tạo một phiên bản của MyClass.Mã hex đề cập đến địa chỉ nơi đối tượng đang được lưu trữ. Một trường hợp khác đang trỏ đến một địa chỉ khác.

Bây giờ chúng ta hãy xác định một biến bên trong lớp MyClass() và lấy biến từ thể hiện của lớp đó như được hiển thị trong đoạn mã sau:

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj.var)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj.var)Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

9

9Như thể hiện biết nó được khởi tạo từ lớp nào, vì vậy khi được yêu cầu một thuộc tính từ một thể hiện, thể hiện sẽ tìm thuộc tính và lớp. Đây được gọi làattribute lookup.

Phương pháp phiên bản

Một hàm được định nghĩa trong một lớp được gọi là method.Một phương thức thể hiện yêu cầu một thể hiện để gọi nó và không yêu cầu trình trang trí. Khi tạo một phương thức phiên bản, tham số đầu tiên luôn làself. Mặc dù chúng ta có thể gọi nó (tự) bằng bất kỳ tên nào khác, nhưng nên sử dụng self, vì nó là một quy ước đặt tên.

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

obj = MyClass()

print(obj.var)

obj.firstM()Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

9

hello, WorldLưu ý rằng trong chương trình trên, chúng ta đã định nghĩa một phương thức với đối số là self. Nhưng chúng ta không thể gọi phương thức vì chúng ta chưa khai báo bất kỳ đối số nào cho nó.

class MyClass(object):

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

print(self)

obj = MyClass()

obj.firstM()

print(obj)Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

hello, World

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>Đóng gói

Đóng gói là một trong những nguyên tắc cơ bản của OOP. OOP cho phép chúng tôi che giấu sự phức tạp của hoạt động bên trong của đối tượng, điều có lợi cho nhà phát triển theo những cách sau:

Đơn giản hóa và dễ hiểu để sử dụng một đối tượng mà không cần biết nội dung bên trong.

Mọi thay đổi đều có thể dễ dàng quản lý.

Lập trình hướng đối tượng chủ yếu dựa vào tính đóng gói. Các thuật ngữ đóng gói và trừu tượng hóa (còn gọi là ẩn dữ liệu) thường được sử dụng như những từ đồng nghĩa. Chúng gần như đồng nghĩa, vì sự trừu tượng đạt được thông qua tính đóng gói.

Tính đóng gói cung cấp cho chúng ta cơ chế hạn chế quyền truy cập vào một số thành phần của đối tượng, điều này có nghĩa là không thể nhìn thấy biểu diễn bên trong của một đối tượng từ bên ngoài định nghĩa đối tượng. Quyền truy cập vào dữ liệu này thường đạt được thông qua các phương pháp đặc biệt -Getters và Setters.

Dữ liệu này được lưu trữ trong các thuộc tính cá thể và có thể được thao tác từ bất kỳ đâu bên ngoài lớp. Để bảo mật, dữ liệu đó chỉ nên được truy cập bằng các phương thức phiên bản. Không được phép truy cập trực tiếp.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.age

zack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

45

Fourty FiveDữ liệu chỉ nên được lưu trữ nếu nó chính xác và hợp lệ, sử dụng cấu trúc xử lý Ngoại lệ. Như chúng ta thấy ở trên, không có giới hạn nào đối với người dùng nhập vào phương thức setAge (). Nó có thể là một chuỗi, một số hoặc một danh sách. Vì vậy, chúng tôi cần phải kiểm tra mã trên để đảm bảo tính chính xác của việc lưu trữ.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.agezack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Init Constructor

Các __init__ method được gọi ngầm ngay sau khi một đối tượng của một lớp được khởi tạo, điều này sẽ khởi tạo đối tượng.

x = MyClass()Dòng mã hiển thị ở trên sẽ tạo một thể hiện mới và gán đối tượng này cho biến cục bộ x.

Hoạt động khởi tạo, đó là calling a class object, tạo một đối tượng trống. Nhiều lớp thích tạo các đối tượng với các thể hiện được tùy chỉnh thành trạng thái ban đầu cụ thể. Do đó, một lớp có thể định nghĩa một phương thức đặc biệt có tên '__init __ ()' như được minh họa:

def __init__(self):

self.data = []Python gọi __init__ trong quá trình khởi tạo để xác định một thuộc tính bổ sung sẽ xảy ra khi một lớp được khởi tạo có thể đang thiết lập một số giá trị bắt đầu cho đối tượng đó hoặc chạy một quy trình bắt buộc trên trình khởi tạo. Vì vậy, trong ví dụ này, một thể hiện mới, được khởi tạo có thể được lấy bằng cách -

x = MyClass()Phương thức __init __ () có thể có một hoặc nhiều đối số để linh hoạt hơn. Init là viết tắt của khởi tạo, vì nó khởi tạo các thuộc tính của cá thể. Nó được gọi là hàm tạo của một lớp.

class myclass(object):

def __init__(self,aaa, bbb):

self.a = aaa

self.b = bbb

x = myclass(4.5, 3)

print(x.a, x.b)Đầu ra

4.5 3Thuộc tính lớp

Thuộc tính được định nghĩa trong lớp được gọi là "thuộc tính lớp" và các thuộc tính được xác định trong hàm được gọi là "thuộc tính cá thể". Trong khi định nghĩa, các thuộc tính này không có tiền tố tự, vì đây là thuộc tính của lớp chứ không phải của một cá thể cụ thể.

Các thuộc tính của lớp có thể được truy cập bởi chính lớp (className.attributeName) cũng như bởi các thể hiện của lớp (inst.attributeName). Vì vậy, các cá thể có quyền truy cập vào cả thuộc tính cá thể cũng như các thuộc tính lớp.

>>> class myclass():

age = 21

>>> myclass.age

21

>>> x = myclass()

>>> x.age

21

>>>Một thuộc tính lớp có thể được ghi đè trong một trường hợp, mặc dù nó không phải là một phương pháp tốt để phá vỡ tính đóng gói.

Có một đường dẫn tra cứu cho các thuộc tính trong Python. Đầu tiên là phương thức được định nghĩa trong lớp, và sau đó là lớp bên trên nó.

>>> class myclass(object):

classy = 'class value'

>>> dd = myclass()

>>> print (dd.classy) # This should return the string 'class value'

class value

>>>

>>> dd.classy = "Instance Value"

>>> print(dd.classy) # Return the string "Instance Value"

Instance Value

>>>

>>> # This will delete the value set for 'dd.classy' in the instance.

>>> del dd.classy

>>> >>> # Since the overriding attribute was deleted, this will print 'class

value'.

>>> print(dd.classy)

class value

>>>Chúng tôi đang ghi đè thuộc tính lớp 'class' trong ví dụ dd. Khi nó bị ghi đè, trình thông dịch Python sẽ đọc giá trị được ghi đè. Nhưng một khi giá trị mới bị xóa bằng 'del', giá trị được ghi đè sẽ không còn xuất hiện trong phiên bản, và do đó, việc tra cứu sẽ tăng lên một cấp độ trên và lấy nó từ lớp.

Làm việc với Dữ liệu Lớp và Phiên bản

Trong phần này, chúng ta hãy hiểu cách dữ liệu lớp liên quan đến dữ liệu cá thể. Chúng ta có thể lưu trữ dữ liệu trong một lớp hoặc trong một cá thể. Khi chúng tôi thiết kế một lớp, chúng tôi quyết định dữ liệu nào thuộc về cá thể và dữ liệu nào nên được lưu trữ vào lớp tổng thể.

Một cá thể có thể truy cập dữ liệu lớp. Nếu chúng ta tạo nhiều cá thể, thì những cá thể này có thể truy cập các giá trị thuộc tính riêng lẻ của chúng cũng như dữ liệu lớp tổng thể.

Do đó, dữ liệu lớp là dữ liệu được chia sẻ giữa tất cả các cá thể. Hãy quan sát đoạn mã đưa ra bên dưới để biết cách đặt lệnh dưới tốt hơn

class InstanceCounter(object):

count = 0 # class attribute, will be accessible to all instances

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

InstanceCounter.count +=1 # Increment the value of class attribute, accessible through class name

# In above line, class ('InstanceCounter') act as an object

def set_val(self, newval):

self.val = newval

def get_val(self):

return self.val

def get_count(self):

return InstanceCounter.count

a = InstanceCounter(9)

b = InstanceCounter(18)

c = InstanceCounter(27)

for obj in (a, b, c):

print ('val of obj: %s' %(obj.get_val())) # Initialized value ( 9, 18, 27)

print ('count: %s' %(obj.get_count())) # always 3Đầu ra

val of obj: 9

count: 3

val of obj: 18

count: 3

val of obj: 27

count: 3Nói tóm lại, các thuộc tính của lớp là giống nhau cho tất cả các trường hợp của lớp trong khi các thuộc tính cá thể là riêng cho mỗi trường hợp. Đối với hai trường hợp khác nhau, chúng ta sẽ có hai thuộc tính cá thể khác nhau.

class myClass:

class_attribute = 99

def class_method(self):

self.instance_attribute = 'I am instance attribute'

print (myClass.__dict__)Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

{'__module__': '__main__', 'class_attribute': 99, 'class_method': <function myClass.class_method at 0x04128D68>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__doc__': None}Thuộc tính instance myClass.__dict__ như hình -

>>> a = myClass()

>>> a.class_method()

>>> print(a.__dict__)

{'instance_attribute': 'I am instance attribute'}Chương này nói chi tiết về các hàm tích hợp sẵn khác nhau trong Python, các thao tác nhập / xuất tệp và các khái niệm nạp chồng.

Các hàm tích hợp trong Python

Trình thông dịch Python có một số hàm được gọi là hàm tích hợp sẵn có sẵn để sử dụng. Trong phiên bản mới nhất của nó, Python chứa 68 hàm tích hợp như được liệt kê trong bảng dưới đây:

| CHỨC NĂNG TÍCH HỢP SẴN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abs () | dict () | Cứu giúp() | min () | setattr () |

| tất cả() | dir () | hex () | kế tiếp() | lát () |

| bất kì() | divmod () | Tôi() | vật() | đã sắp xếp () |

| ascii () | liệt kê () | đầu vào() | oct () | staticmethod () |

| thùng rác() | eval () | int () | mở() | str () |

| bool () | hành () | isinstance () | ord () | Tổng() |

| bytearray () | bộ lọc () | Issubclass () | pow () | siêu() |

| byte () | Phao nổi() | iter () | in() | tuple () |

| callable () | định dạng() | len () | bất động sản() | kiểu() |

| chr () | frozenset () | danh sách() | phạm vi() | vars () |

| classmethod () | getattr () | người dân địa phương () | repr () | zip () |

| biên dịch () | hình cầu () | bản đồ() | đảo ngược () | __import __ () |

| phức tạp() | hasattr () | max () | tròn() | |

| delattr () | băm () | memoryview () | bộ() | |

Phần này thảo luận ngắn gọn về một số chức năng quan trọng -

hàm len ()

Hàm len () lấy độ dài của chuỗi, danh sách hoặc tập hợp. Nó trả về độ dài hoặc số lượng mục của một đối tượng, trong đó đối tượng có thể là một chuỗi, danh sách hoặc một tập hợp.

>>> len(['hello', 9 , 45.0, 24])

4Hàm len () hoạt động bên trong như list.__len__() hoặc là tuple.__len__(). Do đó, lưu ý rằng len () chỉ hoạt động trên các đối tượng có __len__() phương pháp.

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set1.__len__()

4Tuy nhiên, trong thực tế, chúng tôi thích len() thay cho __len__() hoạt động vì những lý do sau:

Nó hiệu quả hơn. Và không nhất thiết phải viết một phương thức cụ thể để từ chối quyền truy cập vào các phương thức đặc biệt như __len__.

Nó rất dễ dàng để bảo trì.

Nó hỗ trợ khả năng tương thích ngược.

Đã đảo ngược (seq)

Nó trả về trình lặp ngược. seq phải là một đối tượng có phương thức __reversed __ () hoặc hỗ trợ giao thức trình tự (phương thức __len __ () và phương thức __getitem __ ()). Nó thường được sử dụng trongfor vòng lặp khi chúng ta muốn lặp lại các mục từ sau ra trước.

>>> normal_list = [2, 4, 5, 7, 9]

>>>

>>> class CustomSequence():

def __len__(self):

return 5

def __getitem__(self,index):

return "x{0}".format(index)

>>> class funkyback():

def __reversed__(self):

return 'backwards!'

>>> for seq in normal_list, CustomSequence(), funkyback():

print('\n{}: '.format(seq.__class__.__name__), end="")

for item in reversed(seq):

print(item, end=", ")Vòng lặp for ở cuối in ra danh sách đảo ngược của một danh sách bình thường và các trường hợp của hai chuỗi tùy chỉnh. Kết quả cho thấyreversed() hoạt động trên cả ba trong số chúng, nhưng có kết quả rất khác khi chúng tôi xác định __reversed__.

Đầu ra

Bạn có thể quan sát kết quả sau khi thực thi đoạn mã được đưa ra ở trên:

list: 9, 7, 5, 4, 2,

CustomSequence: x4, x3, x2, x1, x0,

funkyback: b, a, c, k, w, a, r, d, s, !,Liệt kê

Các enumerate () phương thức thêm một bộ đếm vào một có thể lặp lại và trả về đối tượng liệt kê.

Cú pháp của enumerate () là -

enumerate(iterable, start = 0)Đây là đối số thứ hai start là tùy chọn và theo mặc định, chỉ mục bắt đầu bằng không (0).

>>> # Enumerate

>>> names = ['Rajesh', 'Rahul', 'Aarav', 'Sahil', 'Trevor']

>>> enumerate(names)

<enumerate object at 0x031D9F80>

>>> list(enumerate(names))

[(0, 'Rajesh'), (1, 'Rahul'), (2, 'Aarav'), (3, 'Sahil'), (4, 'Trevor')]

>>>Vì thế enumerate()trả về một trình lặp tạo ra một bộ lưu giữ số lượng các phần tử trong chuỗi được truyền vào. Vì giá trị trả về là một trình lặp, việc truy cập trực tiếp vào nó không hữu ích lắm. Một cách tiếp cận tốt hơn cho enumerate () là giữ số lượng trong vòng lặp for.

>>> for i, n in enumerate(names):

print('Names number: ' + str(i))

print(n)

Names number: 0

Rajesh

Names number: 1

Rahul

Names number: 2

Aarav

Names number: 3

Sahil

Names number: 4

TrevorCó nhiều hàm khác trong thư viện chuẩn và đây là một danh sách khác về một số hàm được sử dụng rộng rãi hơn -

hasattr, getattr, setattr và delattr, cho phép các thuộc tính của một đối tượng được thao tác bởi tên chuỗi của chúng.

all và any, chấp nhận một đối tượng có thể lặp lại và trả về True nếu tất cả hoặc bất kỳ mục nào được đánh giá là đúng.

nzip, lấy hai hoặc nhiều chuỗi và trả về một chuỗi bộ giá trị mới, trong đó mỗi bộ giá trị chứa một giá trị duy nhất từ mỗi chuỗi.

Tệp I / O

Khái niệm tệp gắn liền với thuật ngữ lập trình hướng đối tượng. Python đã bao bọc giao diện mà hệ điều hành cung cấp dưới dạng trừu tượng cho phép chúng ta làm việc với các đối tượng tệp.

Các open()chức năng tích hợp được sử dụng để mở một tệp và trả về một đối tượng tệp. Đây là hàm được sử dụng phổ biến nhất với hai đối số:

open(filename, mode)Hàm open () gọi hai đối số, đầu tiên là tên tệp và thứ hai là chế độ. Chế độ ở đây có thể là 'r' cho chế độ chỉ đọc, 'w' để chỉ ghi (tệp hiện có có cùng tên sẽ bị xóa) và 'a' mở tệp để thêm vào, mọi dữ liệu được ghi vào tệp sẽ tự động được thêm vào đến cuối cùng. 'r +' mở tệp để đọc và ghi. Chế độ mặc định là chỉ đọc.

Trên windows, 'b' được thêm vào chế độ sẽ mở tệp ở chế độ nhị phân, vì vậy cũng có các chế độ như 'rb', 'wb' và 'r + b'.

>>> text = 'This is the first line'

>>> file = open('datawork','w')

>>> file.write(text)

22

>>> file.close()Trong một số trường hợp, chúng tôi chỉ muốn thêm vào tệp hiện có thay vì ghi đè nó, vì điều đó chúng tôi có thể cung cấp giá trị 'a' làm đối số chế độ, để nối vào cuối tệp, thay vì ghi đè hoàn toàn tệp hiện có các nội dung.

>>> f = open('datawork','a')

>>> text1 = ' This is second line'

>>> f.write(text1)

20

>>> f.close()Khi tệp được mở để đọc, chúng ta có thể gọi phương thức read, readline hoặc readlines để lấy nội dung của tệp. Phương thức read trả về toàn bộ nội dung của tệp dưới dạng đối tượng str hoặc byte, tùy thuộc vào đối số thứ hai có phải là 'b' hay không.

Để có thể đọc được và để tránh đọc một tệp lớn trong một lần, tốt hơn là sử dụng vòng lặp for trực tiếp trên một đối tượng tệp. Đối với tệp văn bản, nó sẽ đọc từng dòng, từng dòng một và chúng ta có thể xử lý nó bên trong thân vòng lặp. Tuy nhiên, đối với các tệp nhị phân, tốt hơn nên đọc các phần dữ liệu có kích thước cố định bằng phương thức read (), chuyển một tham số cho số byte tối đa để đọc.

>>> f = open('fileone','r+')

>>> f.readline()

'This is the first line. \n'

>>> f.readline()

'This is the second line. \n'Ghi vào tệp, thông qua phương thức ghi trên các đối tượng tệp sẽ ghi một đối tượng chuỗi (byte đối với dữ liệu nhị phân) vào tệp. Phương thức writelines chấp nhận một chuỗi các chuỗi và ghi từng giá trị được lặp vào tệp. Phương thức writelines không thêm một dòng mới sau mỗi mục trong chuỗi.

Cuối cùng, phương thức close () sẽ được gọi khi chúng ta đọc hoặc ghi tệp xong, để đảm bảo mọi lần ghi trong bộ đệm đều được ghi vào đĩa, rằng tệp đã được dọn sạch đúng cách và tất cả các tài nguyên gắn liền với tệp được giải phóng trở lại hệ điều hành. Đó là một cách tiếp cận tốt hơn để gọi phương thức close () nhưng về mặt kỹ thuật, điều này sẽ tự động xảy ra khi tập lệnh tồn tại.

Một giải pháp thay thế cho phương thức nạp

Nạp chồng phương thức đề cập đến việc có nhiều phương thức có cùng tên chấp nhận các tập đối số khác nhau.

Với một phương thức hoặc một hàm duy nhất, chúng ta có thể tự chỉ định số lượng tham số. Tùy thuộc vào định nghĩa hàm, nó có thể được gọi với không, một, hai hoặc nhiều tham số.

class Human:

def sayHello(self, name = None):

if name is not None:

print('Hello ' + name)

else:

print('Hello ')

#Create Instance

obj = Human()

#Call the method, else part will be executed

obj.sayHello()

#Call the method with a parameter, if part will be executed

obj.sayHello('Rahul')Đầu ra

Hello

Hello RahulĐối số mặc định

Chức năng cũng là đối tượng

Một đối tượng có thể gọi là một đối tượng có thể chấp nhận một số đối số và có thể sẽ trả về một đối tượng. Một hàm là đối tượng có thể gọi đơn giản nhất trong Python, nhưng có những đối tượng khác giống như các lớp hoặc các cá thể lớp nhất định.

Mọi hàm trong Python là một đối tượng. Đối tượng có thể chứa các phương thức hoặc hàm nhưng đối tượng không nhất thiết phải là một hàm.

def my_func():

print('My function was called')

my_func.description = 'A silly function'

def second_func():

print('Second function was called')

second_func.description = 'One more sillier function'

def another_func(func):

print("The description:", end=" ")

print(func.description)

print('The name: ', end=' ')

print(func.__name__)

print('The class:', end=' ')

print(func.__class__)

print("Now I'll call the function passed in")

func()

another_func(my_func)

another_func(second_func)Trong đoạn mã trên, chúng ta có thể chuyển hai hàm khác nhau làm đối số vào hàm thứ ba và nhận được Đầu ra khác nhau cho mỗi hàm -

The description: A silly function

The name: my_func

The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in My function was called The description: One more sillier function The name: second_func The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in Second function was called

callable objects

Just as functions are objects that can have attributes set on them, it is possible to create an object that can be called as though it were a function.

In Python any object with a __call__() method can be called using function-call syntax.

Inheritance and Polymorphism

Inheritance and polymorphism – this is a very important concept in Python. You must understand it better if you want to learn.

Inheritance

One of the major advantages of Object Oriented Programming is re-use. Inheritance is one of the mechanisms to achieve the same. Inheritance allows programmer to create a general or a base class first and then later extend it to more specialized class. It allows programmer to write better code.

Using inheritance you can use or inherit all the data fields and methods available in your base class. Later you can add you own methods and data fields, thus inheritance provides a way to organize code, rather than rewriting it from scratch.

In object-oriented terminology when class X extend class Y, then Y is called super/parent/base class and X is called subclass/child/derived class. One point to note here is that only data fields and method which are not private are accessible by child classes. Private data fields and methods are accessible only inside the class.

syntax to create a derived class is −

class BaseClass:

Body of base class

class DerivedClass(BaseClass):

Body of derived class

Inheriting Attributes

Now look at the below example −

Output

We first created a class called Date and pass the object as an argument, here-object is built-in class provided by Python. Later we created another class called time and called the Date class as an argument. Through this call we get access to all the data and attributes of Date class into the Time class. Because of that when we try to get the get_date method from the Time class object tm we created earlier possible.

Object.Attribute Lookup Hierarchy

- The instance

- The class

- Any class from which this class inherits

Inheritance Examples

Let’s take a closure look into the inheritance example −

Let’s create couple of classes to participate in examples −

- Animal − Class simulate an animal

- Cat − Subclass of Animal

- Dog − Subclass of Animal

In Python, constructor of class used to create an object (instance), and assign the value for the attributes.

Constructor of subclasses always called to a constructor of parent class to initialize value for the attributes in the parent class, then it start assign value for its attributes.

Output

In the above example, we see the command attributes or methods we put in the parent class so that all subclasses or child classes will inherits that property from the parent class.

If a subclass try to inherits methods or data from another subclass then it will through an error as we see when Dog class try to call swatstring() methods from that cat class, it throws an error(like AttributeError in our case).

Polymorphism (“MANY SHAPES”)

Polymorphism is an important feature of class definition in Python that is utilized when you have commonly named methods across classes or subclasses. This permits functions to use entities of different types at different times. So, it provides flexibility and loose coupling so that code can be extended and easily maintained over time.

This allows functions to use objects of any of these polymorphic classes without needing to be aware of distinctions across the classes.

Polymorphism can be carried out through inheritance, with subclasses making use of base class methods or overriding them.

Let understand the concept of polymorphism with our previous inheritance example and add one common method called show_affection in both subclasses −

From the example we can see, it refers to a design in which object of dissimilar type can be treated in the same manner or more specifically two or more classes with method of the same name or common interface because same method(show_affection in below example) is called with either type of objects.

Output

So, all animals show affections (show_affection), but they do differently. The “show_affection” behaviors is thus polymorphic in the sense that it acted differently depending on the animal. So, the abstract “animal” concept does not actually “show_affection”, but specific animals(like dogs and cats) have a concrete implementation of the action “show_affection”.

Python itself have classes that are polymorphic. Example, the len() function can be used with multiple objects and all return the correct output based on the input parameter.

Overriding

In Python, when a subclass contains a method that overrides a method of the superclass, you can also call the superclass method by calling

Super(Subclass, self).method instead of self.method.

Example

class Thought(object):

def __init__(self):

pass

def message(self):

print("Thought, always come and go")

class Advice(Thought):

def __init__(self):

super(Advice, self).__init__()

def message(self):

print('Warning: Risk is always involved when you are dealing with market!')

Inheriting the Constructor

If we see from our previous inheritance example, __init__ was located in the parent class in the up ‘cause the child class dog or cat didn’t‘ve __init__ method in it. Python used the inheritance attribute lookup to find __init__ in animal class. When we created the child class, first it will look the __init__ method in the dog class, then it didn’t find it then looked into parent class Animal and found there and called that there. So as our class design became complex we may wish to initialize a instance firstly processing it through parent class constructor and then through child class constructor.

Output

In above example- all animals have a name and all dogs a particular breed. We called parent class constructor with super. So dog has its own __init__ but the first thing that happen is we call super. Super is built in function and it is designed to relate a class to its super class or its parent class.

In this case we saying that get the super class of dog and pass the dog instance to whatever method we say here the constructor __init__. So in another words we are calling parent class Animal __init__ with the dog object. You may ask why we won’t just say Animal __init__ with the dog instance, we could do this but if the name of animal class were to change, sometime in the future. What if we wanna rearrange the class hierarchy,so the dog inherited from another class. Using super in this case allows us to keep things modular and easy to change and maintain.

So in this example we are able to combine general __init__ functionality with more specific functionality. This gives us opportunity to separate common functionality from the specific functionality which can eliminate code duplication and relate class to one another in a way that reflects the system overall design.

Conclusion

__init__ is like any other method; it can be inherited

If a class does not have a __init__ constructor, Python will check its parent class to see if it can find one.

As soon as it finds one, Python calls it and stops looking

We can use the super () function to call methods in the parent class.

We may want to initialize in the parent as well as our own class.

Multiple Inheritance and the Lookup Tree

As its name indicates, multiple inheritance is Python is when a class inherits from multiple classes.

For example, a child inherits personality traits from both parents (Mother and Father).

Python Multiple Inheritance Syntax

To make a class inherits from multiple parents classes, we write the the names of these classes inside the parentheses to the derived class while defining it. We separate these names with comma.

Below is an example of that −

>>> class Mother:

pass

>>> class Father:

pass

>>> class Child(Mother, Father):

pass

>>> issubclass(Child, Mother) and issubclass(Child, Father)

True

Multiple inheritance refers to the ability of inheriting from two or more than two class. The complexity arises as child inherits from parent and parents inherits from the grandparent class. Python climbs an inheriting tree looking for attributes that is being requested to be read from an object. It will check the in the instance, within class then parent class and lastly from the grandparent class. Now the question arises in what order the classes will be searched - breath-first or depth-first. By default, Python goes with the depth-first.

That’s is why in the below diagram the Python searches the dothis() method first in class A. So the method resolution order in the below example will be

Mro- D→B→A→C

Look at the below multiple inheritance diagram −

Let’s go through an example to understand the “mro” feature of an Python.

Output

Example 3

Let’s take another example of “diamond shape” multiple inheritance.

Above diagram will be considered ambiguous. From our previous example understanding “method resolution order” .i.e. mro will be D→B→A→C→A but it’s not. On getting the second A from the C, Python will ignore the previous A. so the mro will be in this case will be D→B→C→A.

Let’s create an example based on above diagram −

Output

Simple rule to understand the above output is- if the same class appear in the method resolution order, the earlier appearances of this class will be remove from the method resolution order.

In conclusion −

Any class can inherit from multiple classes

Python normally uses a “depth-first” order when searching inheriting classes.

But when two classes inherit from the same class, Python eliminates the first appearances of that class from the mro.

Decorators, Static and Class Methods

Functions(or methods) are created by def statement.

Though methods works in exactly the same way as a function except one point where method first argument is instance object.

We can classify methods based on how they behave, like

Simple method − defined outside of a class. This function can access class attributes by feeding instance argument:

def outside_func(():

Instance method −

def func(self,)

Class method − if we need to use class attributes

@classmethod

def cfunc(cls,)

Static method − do not have any info about the class

@staticmethod

def sfoo()

Till now we have seen the instance method, now is the time to get some insight into the other two methods,

Class Method

The @classmethod decorator, is a builtin function decorator that gets passed the class it was called on or the class of the instance it was called on as first argument. The result of that evaluation shadows your function definition.

syntax

class C(object):

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

....

fun: function that needs to be converted into a class method

returns: a class method for function

They have the access to this cls argument, it can’t modify object instance state. That would require access to self.

It is bound to the class and not the object of the class.

Class methods can still modify class state that applies across all instances of the class.

Static Method

A static method takes neither a self nor a cls(class) parameter but it’s free to accept an arbitrary number of other parameters.

syntax

class C(object):

@staticmethod

def fun(arg1, arg2, ...):

...

returns: a static method for function funself.

- A static method can neither modify object state nor class state.

- They are restricted in what data they can access.

When to use what

We generally use class method to create factory methods. Factory methods return class object (similar to a constructor) for different use cases.

We generally use static methods to create utility functions.

Python Design Pattern

Overview

Modern software development needs to address complex business requirements. It also needs to take into account factors such as future extensibility and maintainability. A good design of a software system is vital to accomplish these goals. Design patterns play an important role in such systems.

To understand design pattern, let’s consider below example −

Every car’s design follows a basic design pattern, four wheels, steering wheel, the core drive system like accelerator-break-clutch, etc.

So, all things repeatedly built/ produced, shall inevitably follow a pattern in its design.. it cars, bicycle, pizza, atm machines, whatever…even your sofa bed.

Designs that have almost become standard way of coding some logic/mechanism/technique in software, hence come to be known as or studied as, Software Design Patterns.

Why is Design Pattern Important?

Benefits of using Design Patterns are −

Helps you to solve common design problems through a proven approach.

No ambiguity in the understanding as they are well documented.

Reduce the overall development time.

Helps you deal with future extensions and modifications with more ease than otherwise.

May reduce errors in the system since they are proven solutions to common problems.

Classification of Design Patterns

The GoF (Gang of Four) design patterns are classified into three categories namely creational, structural and behavioral.

Creational Patterns

Creational design patterns separate the object creation logic from the rest of the system. Instead of you creating objects, creational patterns creates them for you. The creational patterns include Abstract Factory, Builder, Factory Method, Prototype and Singleton.

Creational Patterns are not commonly used in Python because of the dynamic nature of the language. Also language itself provide us with all the flexibility we need to create in a sufficient elegant fashion, we rarely need to implement anything on top, like singleton or Factory.

Also these patterns provide a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using a new operator.

Structural Patterns

Sometimes instead of starting from scratch, you need to build larger structures by using an existing set of classes. That’s where structural class patterns use inheritance to build a new structure. Structural object patterns use composition/ aggregation to obtain a new functionality. Adapter, Bridge, Composite, Decorator, Façade, Flyweight and Proxy are Structural Patterns. They offers best ways to organize class hierarchy.

Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral patterns offers best ways of handling communication between objects. Patterns comes under this categories are: Visitor, Chain of responsibility, Command, Interpreter, Iterator, Mediator, Memento, Observer, State, Strategy and Template method are Behavioral Patterns.

Because they represent the behavior of a system, they are used generally to describe the functionality of software systems.

Commonly used Design Patterns

Singleton

It is one of the most controversial and famous of all design patterns. It is used in overly object-oriented languages, and is a vital part of traditional object-oriented programming.

The Singleton pattern is used for,

When logging needs to be implemented. The logger instance is shared by all the components of the system.

The configuration files is using this because cache of information needs to be maintained and shared by all the various components in the system.

Managing a connection to a database.

Here is the UML diagram,

class Logger(object):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if not hasattr(cls, '_logger'):

cls._logger = super(Logger, cls).__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs)

return cls._logger

In this example, Logger is a Singleton.

When __new__ is called, it normally constructs a new instance of that class. When we override it, we first check if our singleton instance has been created or not. If not, we create it using a super call. Thus, whenever we call the constructor on Logger, we always get the exact same instance.

>>>

>>> obj1 = Logger()

>>> obj2 = Logger()

>>> obj1 == obj2

True

>>>

>>> obj1

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

>>> obj2

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

Object Oriented Python - Advanced Features

In this we will look into some of the advanced features which Python provide

Core Syntax in our Class design

In this we will look onto, how Python allows us to take advantage of operators in our classes. Python is largely objects and methods call on objects and this even goes on even when its hidden by some convenient syntax.

>>> var1 = 'Hello'

>>> var2 = ' World!'

>>> var1 + var2

'Hello World!'

>>>

>>> var1.__add__(var2)

'Hello World!'

>>> num1 = 45

>>> num2 = 60

>>> num1.__add__(num2)

105

>>> var3 = ['a', 'b']

>>> var4 = ['hello', ' John']

>>> var3.__add__(var4)

['a', 'b', 'hello', ' John']

So if we have to add magic method __add__ to our own classes, could we do that too. Let’s try to do that.

We have a class called Sumlist which has a contructor __init__ which takes list as an argument called my_list.

class SumList(object):

def __init__(self, my_list):

self.mylist = my_list

def __add__(self, other):

new_list = [ x + y for x, y in zip(self.mylist, other.mylist)]

return SumList(new_list)

def __repr__(self):

return str(self.mylist)

aa = SumList([3,6, 9, 12, 15])

bb = SumList([100, 200, 300, 400, 500])

cc = aa + bb # aa.__add__(bb)

print(cc) # should gives us a list ([103, 206, 309, 412, 515])

Output

[103, 206, 309, 412, 515]

But there are many methods which are internally managed by others magic methods. Below are some of them,

'abc' in var # var.__contains__('abc')

var == 'abc' # var.__eq__('abc')

var[1] # var.__getitem__(1)

var[1:3] # var.__getslice__(1, 3)

len(var) # var.__len__()

print(var) # var.__repr__()

Inheriting From built-in types

Classes can also inherit from built-in types this means inherits from any built-in and take advantage of all the functionality found there.

In below example we are inheriting from dictionary but then we are implementing one of its method __setitem__. This (setitem) is invoked when we set key and value in the dictionary. As this is a magic method, this will be called implicitly.

class MyDict(dict):

def __setitem__(self, key, val):

print('setting a key and value!')

dict.__setitem__(self, key, val)

dd = MyDict()

dd['a'] = 10

dd['b'] = 20

for key in dd.keys():

print('{0} = {1}'.format(key, dd[key]))

Output

setting a key and value!

setting a key and value!

a = 10

b = 20

Let’s extend our previous example, below we have called two magic methods called __getitem__ and __setitem__ better invoked when we deal with list index.

# Mylist inherits from 'list' object but indexes from 1 instead for 0!

class Mylist(list): # inherits from list

def __getitem__(self, index):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

return list.__getitem__(self, index) # this method is called when

# we access a value with subscript like x[1]

def __setitem__(self, index, value):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

list.__setitem__(self, index, value)

x = Mylist(['a', 'b', 'c']) # __init__() inherited from builtin list

print(x) # __repr__() inherited from builtin list

x.append('HELLO'); # append() inherited from builtin list

print(x[1]) # 'a' (Mylist.__getitem__ cutomizes list superclass

# method. index is 1, but reflects 0!

print (x[4]) # 'HELLO' (index is 4 but reflects 3!

Output

['a', 'b', 'c']

a

HELLO

In above example, we set a three item list in Mylist and implicitly __init__ method is called and when we print the element x, we get the three item list ([‘a’,’b’,’c’]). Then we append another element to this list. Later we ask for index 1 and index 4. But if you see the output, we are getting element from the (index-1) what we have asked for. As we know list indexing start from 0 but here the indexing start from 1 (that’s why we are getting the first item of the list).

Naming Conventions

In this we will look into names we’ll used for variables especially private variables and conventions used by Python programmers worldwide. Although variables are designated as private but there is not privacy in Python and this by design. Like any other well documented languages, Python has naming and style conventions that it promote although it doesn’t enforce them. There is a style guide written by “Guido van Rossum” the originator of Python, that describe the best practices and use of name and is called PEP8. Here is the link for this, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/

PEP stands for Python enhancement proposal and is a series of documentation that distributed among the Python community to discuss proposed changes. For example it is recommended all,

- Module names − all_lower_case

- Class names and exception names − CamelCase

- Global and local names − all_lower_case

- Functions and method names − all_lower_case

- Constants − ALL_UPPER_CASE

These are just the recommendation, you can vary if you like. But as most of the developers follows these recommendation so might me your code is less readable.

Why conform to convention?

We can follow the PEP recommendation we it allows us to get,

- More familiar to the vast majority of developers

- Clearer to most readers of your code.

- Will match style of other contributers who work on same code base.

- Mark of a professional software developers

- Everyone will accept you.

Variable Naming − ‘Public’ and ‘Private’

In Python, when we are dealing with modules and classes, we designate some variables or attribute as private. In Python, there is no existence of “Private” instance variable which cannot be accessed except inside an object. Private simply means they are simply not intended to be used by the users of the code instead they are intended to be used internally. In general, a convention is being followed by most Python developers i.e. a name prefixed with an underscore for example. _attrval (example below) should be treated as a non-public part of the API or any Python code, whether it is a function, a method or a data member. Below is the naming convention we follow,