Objektorientiertes Python - Kurzanleitung

Programmiersprachen und verschiedene Methoden tauchen ständig auf. Objektorientierte Programmierung ist eine solche Methode, die in den letzten Jahren sehr populär geworden ist.

In diesem Kapitel werden die Funktionen der Programmiersprache Python erläutert, die sie zu einer objektorientierten Programmiersprache machen.

Klassifizierungsschema für die Sprachprogrammierung

Python kann unter objektorientierten Programmiermethoden charakterisiert werden. Das folgende Bild zeigt die Eigenschaften verschiedener Programmiersprachen. Beachten Sie die Funktionen von Python, die es objektorientiert machen.

| Langauage Klassen | Kategorien | Sprachen |

|---|---|---|

| Programmierparadigma | Verfahren | C, C ++, C #, Ziel-C, Java, Los |

| Skripting | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, PHP, Ruby | |

| Funktionell | Clojure, Eralang, Haskell, Scala | |

| Zusammenstellungsklasse | Statisch | C, C ++, C #, Ziel-C, Java, Go, Haskell, Scala |

| Dynamisch | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, PHP, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang | |

| Typklasse | Stark | C #, Java, Go, Python, Rubin, Clojure, Erlang, Haskell, Scala |

| Schwach | C, C ++, C #, Ziel-C, CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Perl, Php | |

| Speicherklasse | Gelang es | Andere |

| Nicht verwaltet | C, C ++, C #, Ziel-C |

Was ist objektorientierte Programmierung?

Object Orientedbedeutet auf Objekte gerichtet. Mit anderen Worten bedeutet dies funktional auf die Modellierung von Objekten gerichtet. Dies ist eine der vielen Techniken, die zur Modellierung komplexer Systeme verwendet werden, indem eine Sammlung interagierender Objekte über ihre Daten und ihr Verhalten beschrieben wird.

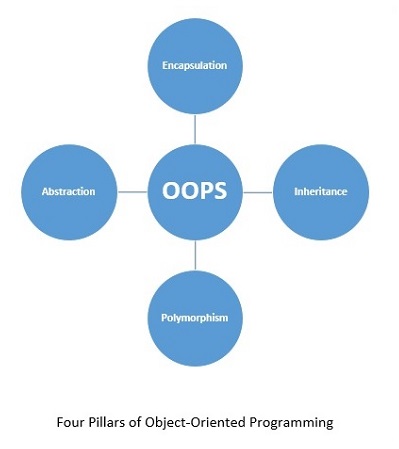

Python, eine objektorientierte Programmierung (OOP), ist eine Programmiermethode, die sich auf die Verwendung von Objekten und Klassen zum Entwerfen und Erstellen von Anwendungen konzentriert. Die wichtigsten Säulen der objektorientierten Programmierung (OOP) sind Inheritance, Polymorphism, Abstraction, Anzeige Encapsulation.

Objektorientierte Analyse (OOA) ist der Prozess der Untersuchung eines Problems, Systems oder einer Aufgabe und der Identifizierung der Objekte und Interaktionen zwischen ihnen.

Warum objektorientierte Programmierung wählen?

Python wurde mit einem objektorientierten Ansatz entwickelt. OOP bietet folgende Vorteile:

Bietet eine klare Programmstruktur, mit der sich Probleme der realen Welt und ihre Lösungen leicht abbilden lassen.

Erleichtert die einfache Wartung und Änderung des vorhandenen Codes.

Verbessert die Programmmodularität, da jedes Objekt unabhängig vorhanden ist und neue Funktionen problemlos hinzugefügt werden können, ohne die vorhandenen zu stören.

Bietet ein gutes Framework für Codebibliotheken, in dem gelieferte Komponenten vom Programmierer einfach angepasst und geändert werden können.

Verbessert die Wiederverwendbarkeit von Code

Prozedurale vs. objektorientierte Programmierung

Die prozedurale Programmierung wird aus der strukturellen Programmierung abgeleitet, die auf den Konzepten von basiert functions/procedure/routines. In der prozedurorientierten Programmierung ist es einfach, auf die Daten zuzugreifen und diese zu ändern. Andererseits ermöglicht die objektorientierte Programmierung (OOP) die Zerlegung eines Problems in eine Anzahl von aufgerufenen Einheitenobjectsund erstellen Sie dann die Daten und Funktionen um diese Objekte. Es konzentriert sich mehr auf die Daten als auf Prozeduren oder Funktionen. Auch in OOP sind Daten ausgeblendet und können nicht durch externe Prozeduren abgerufen werden.

Die Tabelle im folgenden Bild zeigt die Hauptunterschiede zwischen POP- und OOP-Ansatz.

Unterschied zwischen prozedural orientierter Programmierung (POP) vs. Objektorientierte Programmierung (OOP).

| Verfahrensorientierte Programmierung | Objekt orientierte Programmierung | |

|---|---|---|

| Beyogen auf | In Pop liegt der gesamte Fokus auf Daten und Funktionen | Hoppla basiert auf einem realen Szenario. Das gesamte Programm ist in kleine Teile unterteilt, die als Objekt bezeichnet werden |

| Wiederverwendbarkeit | Begrenzte Wiederverwendung von Code | Wiederverwendung von Code |

| Ansatz | Top-down-Ansatz | Objektorientiertes Design |

| Zugriffsspezifizierer | Keine | Öffentlich, privat und geschützt |

| Datenbewegung | Daten können sich frei von Funktionen zu Funktionen im System bewegen | In Ups können Daten über Mitgliedsfunktionen verschoben und miteinander kommuniziert werden |

| Datenzugriff | In Pop verwenden die meisten Funktionen globale Daten für die Freigabe, auf die von Funktion zu Funktion im System frei zugegriffen werden kann | In Ups können Daten nicht frei von Methode zu Methode verschoben werden. Sie können öffentlich oder privat aufbewahrt werden, damit wir den Zugriff auf Daten steuern können |

| Ausblenden von Daten | In Pop, so spezielle Art, Daten zu verbergen, so ein bisschen weniger sicher | Es bietet Daten versteckt, so viel sicherer |

| Überlastung | Nicht möglich | Funktionen und Überlastung des Bedieners |

| Beispielsprachen | C, VB, Fortran, Pascal | C ++, Python, Java, C # |

| Abstraktion | Verwendet Abstraktion auf Prozedurebene | Verwendet Abstraktion auf Klassen- und Objektebene |

Prinzipien der objektorientierten Programmierung

Die objektorientierte Programmierung (OOP) basiert auf dem Konzept von objects eher als Aktionen, und dataeher als Logik. Damit eine Programmiersprache objektorientiert ist, sollte sie über einen Mechanismus verfügen, der das Arbeiten mit Klassen und Objekten sowie die Implementierung und Verwendung der grundlegenden objektorientierten Prinzipien und Konzepte ermöglicht, nämlich Vererbung, Abstraktion, Kapselung und Polymorphismus.

Lassen Sie uns kurz jede der Säulen der objektorientierten Programmierung verstehen -

Verkapselung

Diese Eigenschaft verbirgt unnötige Details und erleichtert die Verwaltung der Programmstruktur. Die Implementierung und der Status jedes Objekts sind hinter genau definierten Grenzen verborgen und bieten eine saubere und einfache Schnittstelle für die Arbeit mit ihnen. Eine Möglichkeit, dies zu erreichen, besteht darin, die Daten privat zu machen.

Erbe

Die Vererbung, auch Generalisierung genannt, ermöglicht es uns, eine hierarchische Beziehung zwischen Klassen und Objekten zu erfassen. Zum Beispiel ist eine "Frucht" eine Verallgemeinerung von "Orange". Vererbung ist aus Sicht der Wiederverwendung von Code sehr nützlich.

Abstraktion

Diese Eigenschaft ermöglicht es uns, die Details auszublenden und nur die wesentlichen Merkmale eines Konzepts oder Objekts freizulegen. Zum Beispiel weiß eine Person, die einen Roller fährt, dass beim Drücken einer Hupe ein Ton ausgegeben wird, aber sie hat keine Ahnung, wie der Ton beim Drücken der Hupe tatsächlich erzeugt wird.

Polymorphismus

Polymorphismus bedeutet viele Formen. Das heißt, eine Sache oder Handlung ist auf verschiedene Formen oder Arten vorhanden. Ein gutes Beispiel für Polymorphismus ist die Überladung von Konstruktoren in Klassen.

Objektorientiertes Python

Das Herzstück der Python-Programmierung ist object und OOPSie müssen sich jedoch nicht darauf beschränken, die OOP zu verwenden, indem Sie Ihren Code in Klassen organisieren. OOP ergänzt die gesamte Designphilosophie von Python und fördert eine saubere und pragmatische Art der Programmierung. OOP ermöglicht auch das Schreiben größerer und komplexer Programme.

Module vs. Klassen und Objekte

Module sind wie "Wörterbücher"

Beachten Sie bei der Arbeit an Modulen die folgenden Punkte:

Ein Python-Modul ist ein Paket zum Einkapseln von wiederverwendbarem Code.

Module befinden sich in einem Ordner mit einem __init__.py Datei darauf.

Module enthalten Funktionen und Klassen.

Module werden mit dem importiert import Stichwort.

Denken Sie daran, dass ein Wörterbuch ein ist key-valuePaar. Das heißt, wenn Sie ein Wörterbuch mit einem Schlüssel habenEmployeID und wenn Sie es abrufen möchten, müssen Sie die folgenden Codezeilen verwenden:

employee = {“EmployeID”: “Employee Unique Identity!”}

print (employee [‘EmployeID])Sie müssen an Modulen mit dem folgenden Prozess arbeiten -

Ein Modul ist eine Python-Datei mit einigen Funktionen oder Variablen.

Importieren Sie die gewünschte Datei.

Jetzt können Sie mit dem '.' Auf die Funktionen oder Variablen in diesem Modul zugreifen. (dot) Operator.

Betrachten Sie ein Modul mit dem Namen employee.py mit einer Funktion darin aufgerufen employee. Der Code der Funktion ist unten angegeben -

# this goes in employee.py

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)Importieren Sie nun das Modul und greifen Sie auf die Funktion zu EmployeID - -

import employee

employee. EmployeID()Sie können eine Variable mit dem Namen einfügen Age, wie gezeigt -

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)

# just a variable

Age = “Employee age is **”Greifen Sie nun wie folgt auf diese Variable zu:

import employee

employee.EmployeID()

print(employee.Age)Vergleichen wir dies jetzt mit dem Wörterbuch -

Employee[‘EmployeID’] # get EmployeID from employee

Employee.employeID() # get employeID from the module

Employee.Age # get access to variableBeachten Sie, dass es in Python ein allgemeines Muster gibt -

Nehmen Sie eine key = value Stil Container

Holen Sie sich etwas daraus mit dem Namen des Schlüssels

Beim Vergleichen des Moduls mit einem Wörterbuch sind beide ähnlich, mit Ausnahme der folgenden:

Im Falle der dictionaryist der Schlüssel eine Zeichenfolge und die Syntax ist [Schlüssel].

Im Falle der moduleDer Schlüssel ist ein Bezeichner und die Syntax lautet .key.

Klassen sind wie Module

Das Modul ist ein spezielles Wörterbuch, in dem Python-Code gespeichert werden kann, sodass Sie mit dem '.' Operator. Eine Klasse ist eine Möglichkeit, eine Gruppierung von Funktionen und Daten in einen Container zu legen, damit Sie mit dem Operator '.''auf sie zugreifen können.

Wenn Sie eine Klasse erstellen müssen, die dem Mitarbeitermodul ähnelt, können Sie dies mit dem folgenden Code tun:

class employee(object):

def __init__(self):

self. Age = “Employee Age is ##”

def EmployeID(self):

print (“This is just employee unique identity”)Note- Klassen werden Modulen vorgezogen, da Sie sie unverändert und ohne große Störungen wiederverwenden können. Während Sie mit Modulen arbeiten, haben Sie nur eines mit dem gesamten Programm.

Objekte sind wie Mini-Importe

Eine Klasse ist wie eine mini-module und Sie können auf ähnliche Weise wie für Klassen importieren, indem Sie das aufgerufene Konzept verwenden instantiate. Beachten Sie, dass Sie beim Instanziieren einer Klasse eine erhaltenobject.

Sie können ein Objekt instanziieren, ähnlich wie beim Aufrufen einer Klasse wie einer Funktion.

this_obj = employee() # Instantiatethis_obj.EmployeID() # get EmployeId from the class

print(this_obj.Age) # get variable AgeSie können dies auf eine der folgenden drei Arten tun:

# dictionary style

Employee[‘EmployeID’]

# module style

Employee.EmployeID()

Print(employee.Age)

# Class style

this_obj = employee()

this_obj.employeID()

Print(this_obj.Age)In diesem Kapitel wird das Einrichten der Python-Umgebung auf Ihrem lokalen Computer ausführlich erläutert.

Voraussetzungen und Toolkits

Bevor Sie mit Python fortfahren, empfehlen wir Ihnen zu überprüfen, ob die folgenden Voraussetzungen erfüllt sind:

Die neueste Version von Python ist auf Ihrem Computer installiert

Eine IDE oder ein Texteditor ist installiert

Sie sind mit dem Schreiben und Debuggen in Python vertraut, dh Sie können in Python Folgendes tun:

Kann Python-Programme schreiben und ausführen.

Debuggen Sie Programme und diagnostizieren Sie Fehler.

Arbeiten Sie mit grundlegenden Datentypen.

Schreiben for Schleifen, while Schleifen und if Aussagen

Code functions

Wenn Sie keine Programmiersprachenerfahrung haben, finden Sie in Python viele Anfänger-Tutorials

https://www.tutorialpoints.com/Python installieren

Die folgenden Schritte zeigen Ihnen ausführlich, wie Sie Python auf Ihrem lokalen Computer installieren.

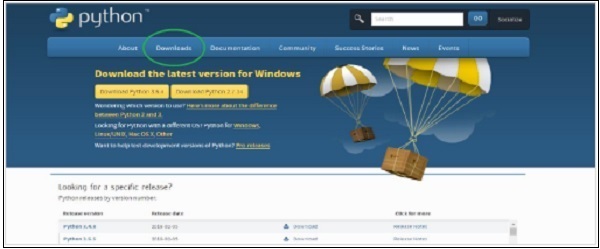

Step 1 - Gehen Sie zur offiziellen Python-Website https://www.python.org/, Klick auf das Downloads Menü und wählen Sie die neueste oder eine stabile Version Ihrer Wahl.

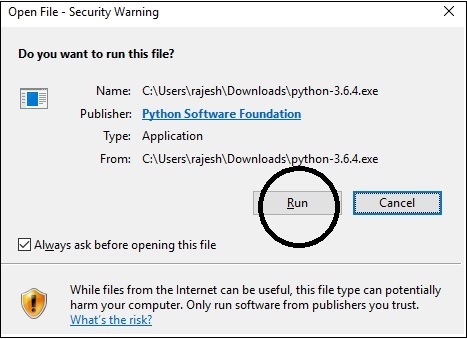

Step 2- Speichern Sie die heruntergeladene Python-Installations-Exe-Datei und öffnen Sie sie, sobald Sie sie heruntergeladen haben. Klicke aufRun und wähle Next Option standardmäßig und beenden Sie die Installation.

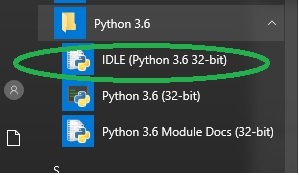

Step 3- Nach der Installation sollte nun das Python-Menü angezeigt werden (siehe Abbildung unten). Starten Sie das Programm, indem Sie IDLE (Python GUI) wählen.

Dadurch wird die Python-Shell gestartet. Geben Sie einfache Befehle ein, um die Installation zu überprüfen.

IDE auswählen

Eine integrierte Entwicklungsumgebung ist ein Texteditor, der auf die Softwareentwicklung ausgerichtet ist. Sie müssen eine IDE installieren, um den Ablauf Ihrer Programmierung zu steuern und Projekte zu gruppieren, wenn Sie an Python arbeiten. Hier sind einige der online verfügbaren IDEs. Sie können eine nach Belieben auswählen.

- Pycharm IDE

- Komodo IDE

- Eric Python IDE

Note - Eclipse IDE wird hauptsächlich in Java verwendet, verfügt jedoch über ein Python-Plugin.

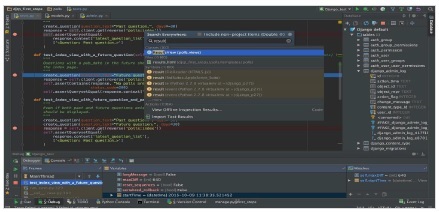

Pycharm

Pycharm, die plattformübergreifende IDE, ist eine der beliebtesten derzeit verfügbaren IDE. Es bietet Codierungsunterstützung und -analyse mit Code-Vervollständigung, Projekt- und Code-Navigation, integrierten Komponententests, Integration der Versionskontrolle, Debugging und vielem mehr

Download-Link

https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/download/#section=windowsLanguages Supported - Python, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Kaffeeskript, TypeScript, Cython, AngularJS, Node.js, Vorlagensprachen.

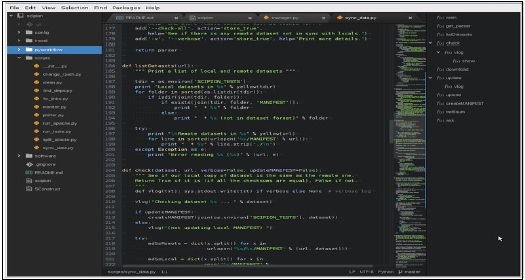

Bildschirmfoto

Warum wählen?

PyCharm bietet seinen Benutzern die folgenden Funktionen und Vorteile:

- Plattformübergreifende IDE, kompatibel mit Windows, Linux und Mac OS

- Beinhaltet Django IDE sowie CSS- und JavaScript-Unterstützung

- Enthält Tausende von Plugins, integriertes Terminal und Versionskontrolle

- Integriert in Git, SVN und Mercurial

- Bietet intelligente Bearbeitungswerkzeuge für Python

- Einfache Integration mit Virtualenv, Docker und Vagrant

- Einfache Navigations- und Suchfunktionen

- Code-Analyse und Refactoring

- Konfigurierbare Injektionen

- Unterstützt Tonnen von Python-Bibliotheken

- Enthält Vorlagen und JavaScript-Debugger

- Beinhaltet Python / Django-Debugger

- Funktioniert mit Google App Engine, zusätzlichen Frameworks und Bibliotheken.

- Verfügt über eine anpassbare Benutzeroberfläche und eine VIM-Emulation

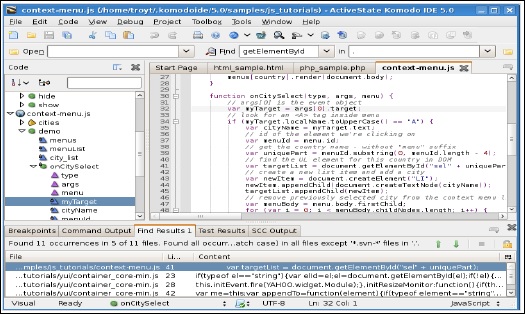

Komodo IDE

Es ist eine polyglotte IDE, die mehr als 100 Sprachen unterstützt und im Wesentlichen für dynamische Sprachen wie Python, PHP und Ruby. Es handelt sich um eine kommerzielle IDE, die 21 Tage lang kostenlos mit voller Funktionalität getestet werden kann. ActiveState ist das Softwareunternehmen, das die Entwicklung der Komodo-IDE verwaltet. Es bietet auch eine gekürzte Version von Komodo, bekannt als Komodo Edit, für einfache Programmieraufgaben.

Diese IDE enthält alle Arten von Funktionen, von den einfachsten bis zu den fortgeschrittensten. Wenn Sie Student oder Freiberufler sind, können Sie es fast die Hälfte des tatsächlichen Preises kaufen. Es ist jedoch für Lehrer und Professoren anerkannter Institutionen und Universitäten völlig kostenlos.

Es verfügt über alle Funktionen, die Sie für die Web- und Mobilentwicklung benötigen, einschließlich der Unterstützung aller Ihrer Sprachen und Frameworks.

Download-Link

Die Download-Links für Komodo Edit (kostenlose Version) und Komodo IDE (kostenpflichtige Version) sind hier angegeben -

Komodo Edit (free)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-editKomodo IDE (paid)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-ide/downloads/ideBildschirmfoto

Warum wählen?

- Leistungsstarke IDE mit Unterstützung für Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby und viele mehr.

- Plattformübergreifende IDE.

Es enthält grundlegende Funktionen wie integrierte Debugger-Unterstützung, automatische Vervollständigung, DOM-Viewer (Document Object Model), Code-Browser, interaktive Shells, Haltepunktkonfiguration, Code-Profilerstellung und integrierte Komponententests. Kurz gesagt, es handelt sich um eine professionelle IDE mit einer Vielzahl produktivitätssteigernder Funktionen.

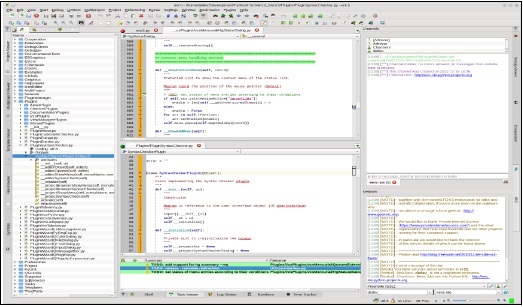

Eric Python IDE

Es ist eine Open-Source-IDE für Python und Ruby. Eric ist ein voll ausgestatteter Editor und eine IDE, die in Python geschrieben wurden. Es basiert auf dem plattformübergreifenden Qt-GUI-Toolkit, das die hochflexible Steuerung des Scintilla-Editors integriert. Die IDE ist sehr konfigurierbar und man kann wählen, was verwendet werden soll und was nicht. Sie können Eric IDE unter folgendem Link herunterladen:

https://eric-ide.python-projects.org/eric-download.htmlWarum wählen?

- Großartige Einrückung, Fehlerhervorhebung.

- Code-Unterstützung

- Code-Vervollständigung

- Codebereinigung mit PyLint

- Schnelle Suche

- Integrierter Python-Debugger.

Bildschirmfoto

Texteditor auswählen

Möglicherweise benötigen Sie nicht immer eine IDE. Für Aufgaben wie das Erlernen des Codierens mit Python oder Arduino oder wenn Sie an einem schnellen Skript im Shell-Skript arbeiten, um einige Aufgaben zu automatisieren, ist ein einfacher und leichter Code-zentrierter Texteditor geeignet. Viele Texteditoren bieten ähnlich wie IDEs Funktionen wie Syntaxhervorhebung und programminterne Skriptausführung. Einige der Texteditoren sind hier angegeben -

- Atom

- Erhabener Text

- Notepad++

Atom Text Editor

Atom ist ein hackbarer Texteditor, der vom Team von GitHub erstellt wurde. Es ist ein kostenloser und Open-Source-Text- und Code-Editor, der bedeutet, dass Sie den gesamten Code lesen, für Ihren eigenen Gebrauch ändern und sogar Verbesserungen beitragen können. Es ist ein plattformübergreifender Texteditor, der mit macOS, Linux und Microsoft Windows kompatibel ist und Plug-Ins unterstützt, die in Node.js und Embedded Git Control geschrieben sind.

Download-Link

https://atom.io/Bildschirmfoto

Unterstützte Sprachen

C / C ++, C #, CSS, CoffeeScript, HTML, JavaScript, Java, JSON, Julia, Objective-C, PHP, Perl, Python, Ruby on Rails, Ruby, Shell-Skript, Scala, SQL, XML, YAML und viele mehr.

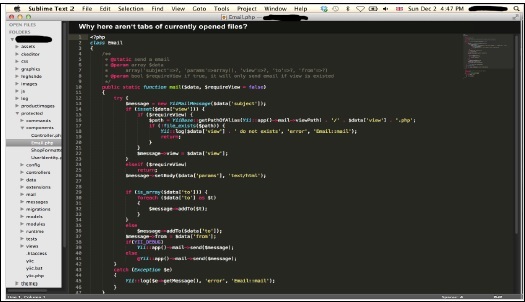

Erhabener Texteditor

Sublime Text ist eine proprietäre Software und bietet Ihnen eine kostenlose Testversion, um sie vor dem Kauf zu testen. Laut stackoverflow.com ist es die viertbeliebteste Entwicklungsumgebung.

Einige der Vorteile sind die unglaubliche Geschwindigkeit, Benutzerfreundlichkeit und Community-Unterstützung. Es unterstützt auch viele Programmiersprachen und Auszeichnungssprachen, und Benutzer können Funktionen mit Plugins hinzufügen, die normalerweise von der Community erstellt und unter Lizenzen für freie Software verwaltet werden.

Bildschirmfoto

Sprache unterstützt

- Python, Ruby, JavaScript usw.

Warum wählen?

Passen Sie Tastenkombinationen, Menüs, Snippets, Makros, Vervollständigungen und mehr an.

Funktion zur automatischen Vervollständigung

- Fügen Sie mithilfe von Snippets, Feldmarkierungen und Platzhaltern schnell Text und Code mit erhabenen Textausschnitten ein

Öffnet sich schnell

Plattformübergreifende Unterstützung für Mac, Linux und Windows.

Bewegen Sie den Cursor dorthin, wo Sie hin möchten

Wählen Sie Mehrere Zeilen, Wörter und Spalten

Editor ++

Es ist ein kostenloser Quellcode-Editor und Notepad-Ersatz, der mehrere Sprachen von Assembly bis XML und einschließlich Python unterstützt. Die Verwendung in der MS Windows-Umgebung unterliegt der GPL-Lizenz. Zusätzlich zur Syntaxhervorhebung verfügt Notepad ++ über einige Funktionen, die für Codierer besonders nützlich sind.

Bildschirmfoto

Hauptmerkmale

- Syntaxhervorhebung und Syntaxfaltung

- PCRE (Perl Compatible Regular Expression) Suchen / Ersetzen

- Vollständig anpassbare GUI

- SAuto Fertigstellung

- Bearbeitung mit Registerkarten

- Multi-View

- Mehrsprachige Umgebung

- Startbar mit verschiedenen Argumenten

Sprachunterstützung

- Fast jede Sprache (über 60 Sprachen) wie Python, C, C ++, C #, Java usw.

Python-Datenstrukturen sind aus syntaktischer Sicht sehr intuitiv und bieten eine große Auswahl an Operationen. Sie müssen die Python-Datenstruktur auswählen, je nachdem, was die Daten beinhalten, ob sie geändert werden müssen oder ob es sich um feste Daten handelt und welcher Zugriffstyp erforderlich ist, z. B. am Anfang / Ende / Zufall usw.

Listen

Eine Liste repräsentiert den vielseitigsten Typ von Datenstruktur in Python. Eine Liste ist ein Container, der durch Kommas getrennte Werte (Elemente oder Elemente) in eckigen Klammern enthält. Listen sind hilfreich, wenn wir mit mehreren verwandten Werten arbeiten möchten. Da Listen Daten zusammenhalten, können wir dieselben Methoden und Operationen für mehrere Werte gleichzeitig ausführen. Listenindizes beginnen bei Null und im Gegensatz zu Zeichenfolgen sind Listen veränderbar.

Datenstruktur - Liste

>>>

>>> # Any Empty List

>>> empty_list = []

>>>

>>> # A list of String

>>> str_list = ['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> # A list of Integers

>>> int_list = [1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>>

>>> #Mixed items list

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>> # To print the list

>>>

>>> print(empty_list)

[]

>>> print(str_list)

['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> print(type(str_list))

<class 'list'>

>>> print(int_list)

[1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>> print(mixed_list)

['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']Zugriff auf Elemente in der Python-Liste

Jedem Element einer Liste wird eine Nummer zugewiesen - das ist der Index oder die Position dieser Nummer. Die Indexierung beginnt immer bei Null, der zweite Index ist Eins und so weiter. Um auf Elemente in einer Liste zuzugreifen, können wir diese Indexnummern in einer eckigen Klammer verwenden. Beachten Sie zum Beispiel den folgenden Code:

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>>

>>> # To access the First Item of the list

>>> mixed_list[0]

'This'

>>> # To access the 4th item

>>> mixed_list[3]

18

>>> # To access the last item of the list

>>> mixed_list[-1]

'list'Leere Objekte

Leere Objekte sind die einfachsten und grundlegendsten in Python integrierten Typen. Wir haben sie mehrmals verwendet, ohne es zu bemerken, und sie auf jede von uns erstellte Klasse erweitert. Der Hauptzweck, eine leere Klasse zu schreiben, besteht darin, etwas vorerst zu blockieren und später zu erweitern und ein Verhalten hinzuzufügen.

Ein Verhalten zu einer Klasse hinzuzufügen bedeutet, eine Datenstruktur durch ein Objekt zu ersetzen und alle Verweise darauf zu ändern. Daher ist es wichtig, die Daten zu überprüfen, ob es sich um ein getarntes Objekt handelt, bevor Sie etwas erstellen. Beachten Sie zum besseren Verständnis den folgenden Code:

>>> #Empty objects

>>>

>>> obj = object()

>>> obj.x = 9

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

obj.x = 9

AttributeError: 'object' object has no attribute 'x'Von oben sehen wir also, dass es nicht möglich ist, Attribute für ein Objekt festzulegen, das direkt instanziiert wurde. Wenn Python zulässt, dass ein Objekt beliebige Attribute hat, benötigt es eine bestimmte Menge an Systemspeicher, um zu verfolgen, welche Attribute jedes Objekt hat, um sowohl den Attributnamen als auch seinen Wert zu speichern. Selbst wenn keine Attribute gespeichert sind, wird eine bestimmte Speichermenge für potenzielle neue Attribute zugewiesen.

Daher deaktiviert Python standardmäßig beliebige Eigenschaften für Objekte und mehrere andere integrierte Funktionen.

>>> # Empty Objects

>>>

>>> class EmpObject:

pass

>>> obj = EmpObject()

>>> obj.x = 'Hello, World!'

>>> obj.x

'Hello, World!'Wenn wir also Eigenschaften gruppieren möchten, können wir sie in einem leeren Objekt speichern, wie im obigen Code gezeigt. Diese Methode wird jedoch nicht immer empfohlen. Denken Sie daran, dass Klassen und Objekte nur verwendet werden sollten, wenn Sie sowohl Daten als auch Verhalten angeben möchten.

Tupel

Tupel ähneln Listen und können Elemente speichern. Sie sind jedoch unveränderlich, sodass wir keine Objekte hinzufügen, entfernen oder ersetzen können. Der Hauptvorteil, den Tupel aufgrund seiner Unveränderlichkeit bietet, besteht darin, dass wir sie als Schlüssel in Wörterbüchern oder an anderen Stellen verwenden können, an denen ein Objekt einen Hashwert benötigt.

Tupel werden zum Speichern von Daten und nicht zum Verhalten verwendet. Wenn Sie Verhalten benötigen, um ein Tupel zu manipulieren, müssen Sie das Tupel an eine Funktion (oder Methode für ein anderes Objekt) übergeben, die die Aktion ausführt.

Da Tupel als Wörterbuchschlüssel fungieren kann, unterscheiden sich die gespeicherten Werte voneinander. Wir können ein Tupel erstellen, indem wir die Werte durch ein Komma trennen. Tupel werden in Klammern gesetzt, sind jedoch nicht obligatorisch. Der folgende Code zeigt zwei identische Zuordnungen.

>>> stock1 = 'MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45

>>> stock2 = ('MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45)

>>> type (stock1)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> type(stock2)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> stock1 == stock2

True

>>>Ein Tupel definieren

Tupel sind der Liste sehr ähnlich, außer dass der gesamte Satz von Elementen in Klammern anstatt in eckigen Klammern eingeschlossen ist.

Genau wie beim Schneiden einer Liste erhalten Sie eine neue Liste und beim Schneiden eines Tupels erhalten Sie ein neues Tupel.

>>> tupl = ('Tuple','is', 'an','IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl[0]

'Tuple'

>>> tupl[-1]

'list'

>>> tupl[1:3]

('is', 'an')Python-Tupel-Methoden

Der folgende Code zeigt die Methoden in Python-Tupeln -

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl.append('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#148>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.append('new')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

>>> tupl.remove('is')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#149>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.remove('is')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'remove'

>>> tupl.index('list')

4

>>> tupl.index('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#151>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.index('new')

ValueError: tuple.index(x): x not in tuple

>>> "is" in tupl

True

>>> tupl.count('is')

1Aus dem oben gezeigten Code können wir verstehen, dass Tupel unveränderlich sind und daher -

Sie cannot Fügen Sie einem Tupel Elemente hinzu.

Sie cannot eine Methode anhängen oder erweitern.

Sie cannot Elemente aus einem Tupel entfernen.

Tupel haben no Methode entfernen oder einfügen.

Anzahl und Index sind die in einem Tupel verfügbaren Methoden.

Wörterbuch

Dictionary ist einer der in Python integrierten Datentypen und definiert Eins-zu-Eins-Beziehungen zwischen Schlüsseln und Werten.

Wörterbücher definieren

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um Informationen zum Definieren eines Wörterbuchs zu erhalten:

>>> # empty dictionary

>>> my_dict = {}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with integer keys

>>> my_dict = { 1:'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with mixed keys

>>> my_dict = {'name': 'Aarav', 1: [ 2, 4, 10]}

>>>

>>> # using built-in function dict()

>>> my_dict = dict({1:'msft', 2:'IT'})

>>>

>>> # From sequence having each item as a pair

>>> my_dict = dict([(1,'msft'), (2,'IT')])

>>>

>>> # Accessing elements of a dictionary

>>> my_dict[1]

'msft'

>>> my_dict[2]

'IT'

>>> my_dict['IT']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#177>", line 1, in <module>

my_dict['IT']

KeyError: 'IT'

>>>Aus dem obigen Code können wir Folgendes beobachten:

Zuerst erstellen wir ein Wörterbuch mit zwei Elementen und weisen es der Variablen zu my_dict. Jedes Element ist ein Schlüssel-Wert-Paar, und der gesamte Satz von Elementen ist in geschweiften Klammern eingeschlossen.

Die Nummer 1 ist der Schlüssel und msftist sein Wert. Ähnlich,2 ist der Schlüssel und IT ist sein Wert.

Sie können Werte per Schlüssel erhalten, aber nicht umgekehrt. Also wenn wir es versuchenmy_dict[‘IT’] , es löst eine Ausnahme aus, weil IT ist kein Schlüssel.

Wörterbücher ändern

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um Informationen zum Ändern eines Wörterbuchs zu erhalten:

>>> # Modifying a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>> my_dict[2] = 'Software'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software'}

>>>

>>> my_dict[3] = 'Microsoft Technologies'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}Aus dem obigen Code können wir beobachten, dass -

Sie können keine doppelten Schlüssel in einem Wörterbuch haben. Durch Ändern des Werts eines vorhandenen Schlüssels wird der alte Wert gelöscht.

Sie können jederzeit neue Schlüssel-Wert-Paare hinzufügen.

Wörterbücher haben keinen Ordnungsbegriff zwischen Elementen. Es sind einfache ungeordnete Sammlungen.

Mischen von Datentypen in einem Wörterbuch

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um zu verstehen, wie Datentypen in einem Wörterbuch gemischt werden:

>>> # Mixing Data Types in a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}

>>> my_dict[4] = 'Operating System'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>> my_dict['Bill Gates'] = 'Owner'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}Aus dem obigen Code können wir beobachten, dass -

Nicht nur Zeichenfolgen, sondern auch Wörterbuchwerte können von jedem Datentyp sein, einschließlich Zeichenfolgen, Ganzzahlen, einschließlich des Wörterbuchs selbst.

Im Gegensatz zu Wörterbuchwerten sind Wörterbuchschlüssel eingeschränkter, können jedoch von einem beliebigen Typ wie Zeichenfolgen, Ganzzahlen oder anderen sein.

Elemente aus Wörterbüchern löschen

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um Informationen zum Löschen von Elementen aus einem Wörterbuch zu erhalten:

>>> # Deleting Items from a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}

>>>

>>> del my_dict['Bill Gates']

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>>

>>> my_dict.clear()

>>> my_dict

{}Aus dem obigen Code können wir beobachten, dass -

del - Mit dieser Option können Sie einzelne Elemente nach Schlüssel aus einem Wörterbuch löschen.

clear - löscht alle Elemente aus einem Wörterbuch.

Sets

Set () ist eine ungeordnete Sammlung ohne doppelte Elemente. Obwohl einzelne Elemente unveränderlich sind, ist das Set selbst veränderlich, dh wir können Elemente / Elemente zum Set hinzufügen oder daraus entfernen. Wir können mathematische Operationen wie Vereinigung, Schnittmenge usw. mit set ausführen.

Obwohl Sets im Allgemeinen mithilfe von Bäumen implementiert werden können, können Sets in Python mithilfe einer Hash-Tabelle implementiert werden. Dies ermöglicht eine hochoptimierte Methode zur Überprüfung, ob ein bestimmtes Element in der Menge enthalten ist

Set erstellen

Ein Set wird erstellt, indem alle Elemente (Elemente) in geschweiften Klammern platziert werden {}, durch Komma oder mithilfe der integrierten Funktion getrennt set(). Beachten Sie die folgenden Codezeilen -

>>> #set of integers

>>> my_set = {1,2,4,8}

>>> print(my_set)

{8, 1, 2, 4}

>>>

>>> #set of mixed datatypes

>>> my_set = {1.0, "Hello World!", (2, 4, 6)}

>>> print(my_set)

{1.0, (2, 4, 6), 'Hello World!'}

>>>Methoden für Mengen

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um die Methoden für Mengen zu verstehen:

>>> >>> #METHODS FOR SETS

>>>

>>> #add(x) Method

>>> topics = {'Python', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>> topics.add('C++')

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>>

>>> #union(s) Method, returns a union of two set.

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>> team = {'Developer', 'Content Writer', 'Editor','Tester'}

>>> group = topics.union(team)

>>> group

{'Tester', 'C#', 'Python', 'Editor', 'Developer', 'C++', 'Java', 'Content

Writer'}

>>> # intersets(s) method, returns an intersection of two sets

>>> inters = topics.intersection(team)

>>> inters

set()

>>>

>>> # difference(s) Method, returns a set containing all the elements of

invoking set but not of the second set.

>>>

>>> safe = topics.difference(team)

>>> safe

{'Python', 'C++', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>>

>>> diff = topics.difference(group)

>>> diff

set()

>>> #clear() Method, Empties the whole set.

>>> group.clear()

>>> group

set()

>>>Operatoren für Sets

Beachten Sie den folgenden Code, um mehr über Operatoren für Mengen zu erfahren:

>>> # PYTHON SET OPERATIONS

>>>

>>> #Creating two sets

>>> set1 = set()

>>> set2 = set()

>>>

>>> # Adding elements to set

>>> for i in range(1,5):

set1.add(i)

>>> for j in range(4,9):

set2.add(j)

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set2

{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Union of set1 and set2

>>> set3 = set1 | set2 # same as set1.union(set2)

>>> print('Union of set1 & set2: set3 = ', set3)

Union of set1 & set2: set3 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Intersection of set1 & set2

>>> set4 = set1 & set2 # same as set1.intersection(set2)

>>> print('Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = ', set4)

Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = {4}

>>>

>>> # Checking relation between set3 and set4

>>> if set3 > set4: # set3.issuperset(set4)

print('Set3 is superset of set4')

elif set3 < set4: #set3.issubset(set4)

print('Set3 is subset of set4')

else: #set3 == set4

print('Set 3 is same as set4')

Set3 is superset of set4

>>>

>>> # Difference between set3 and set4

>>> set5 = set3 - set4

>>> print('Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = ', set5)

Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> # Check if set4 and set5 are disjoint sets

>>> if set4.isdisjoint(set5):

print('Set4 and set5 have nothing in common\n')

Set4 and set5 have nothing in common

>>> # Removing all the values of set5

>>> set5.clear()

>>> set5 set()In diesem Kapitel werden wir objektorientierte Begriffe und Programmierkonzepte im Detail diskutieren. Die Klasse ist nur eine Fabrik für eine Instanz. Diese Factory enthält den Entwurf, der beschreibt, wie die Instanzen erstellt werden. Eine Instanz oder ein Objekt wird aus der Klasse erstellt. In den meisten Fällen können wir mehr als eine Instanz einer Klasse haben. Jede Instanz verfügt über eine Reihe von Attributen, und diese Attribute werden in einer Klasse definiert. Daher wird erwartet, dass jede Instanz einer bestimmten Klasse dieselben Attribute aufweist.

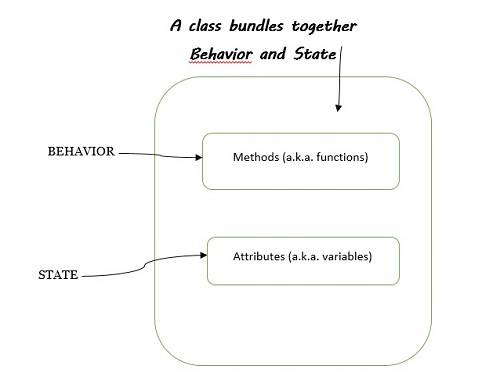

Klassenbündel: Verhalten und Zustand

Mit einer Klasse können Sie das Verhalten und den Status eines Objekts bündeln. Beachten Sie zum besseren Verständnis das folgende Diagramm -

Die folgenden Punkte sind bei der Erörterung von Klassenbündeln bemerkenswert -

Das Wort behavior ist identisch mit function - Es ist ein Code, der etwas tut (oder ein Verhalten implementiert).

Das Wort state ist identisch mit variables - Hier können Werte innerhalb einer Klasse gespeichert werden.

Wenn wir ein Klassenverhalten und einen Status zusammen behaupten, bedeutet dies, dass eine Klasse Funktionen und Variablen packt.

Klassen haben Methoden und Attribute

In Python definiert das Erstellen einer Methode ein Klassenverhalten. Die Wortmethode ist der OOP-Name, der einer Funktion gegeben wird, die innerhalb einer Klasse definiert ist. Zusammenfassend -

Class functions - ist ein Synonym für methods

Class variables - ist ein Synonym für name attributes.

Class - eine Blaupause für eine Instanz mit genauem Verhalten.

Object - Führen Sie in einer der Instanzen der Klasse die in der Klasse definierten Funktionen aus.

Type - gibt die Klasse an, zu der die Instanz gehört

Attribute - Beliebiger Objektwert: object.attribute

Method - ein in der Klasse definiertes "aufrufbares Attribut"

Beachten Sie zum Beispiel den folgenden Code:

var = “Hello, John”

print( type (var)) # < type ‘str’> or <class 'str'>

print(var.upper()) # upper() method is called, HELLO, JOHNSchöpfung und Instanziierung

Der folgende Code zeigt, wie Sie unsere erste Klasse und dann ihre Instanz erstellen.

class MyClass(object):

pass

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj)Hier haben wir eine Klasse namens erstellt MyClassund die keine Aufgabe erledigt. Das Argumentobject im MyClass Klasse beinhaltet Klassenvererbung und wird in späteren Kapiteln besprochen. pass im obigen Code zeigt an, dass dieser Block leer ist, das heißt, es ist eine leere Klassendefinition.

Lassen Sie uns eine Instanz erstellen this_obj von MyClass() Klasse und drucken Sie es wie gezeigt -

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x03B08E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x0369D390>Hier haben wir eine Instanz von erstellt MyClass.Der Hex-Code bezieht sich auf die Adresse, an der das Objekt gespeichert wird. Eine andere Instanz zeigt auf eine andere Adresse.

Definieren wir nun eine Variable innerhalb der Klasse MyClass() und holen Sie sich die Variable aus der Instanz dieser Klasse, wie im folgenden Code gezeigt -

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj.var)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj.var)Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

9

9Da die Instanz weiß, von welcher Klasse sie instanziiert wird, sucht die Instanz bei der Anforderung eines Attributs von einer Instanz nach dem Attribut und der Klasse. Dies nennt man dasattribute lookup.

Instanzmethoden

Eine in einer Klasse definierte Funktion heißt a method.Eine Instanzmethode benötigt eine Instanz, um sie aufzurufen, und benötigt keinen Dekorator. Beim Erstellen einer Instanzmethode ist der erste Parameter immerself. Obwohl wir es (self) bei jedem anderen Namen nennen können, wird empfohlen, self zu verwenden, da es sich um eine Namenskonvention handelt.

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

obj = MyClass()

print(obj.var)

obj.firstM()Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

9

hello, WorldBeachten Sie, dass wir im obigen Programm eine Methode mit self als Argument definiert haben. Wir können die Methode jedoch nicht aufrufen, da wir kein Argument dafür deklariert haben.

class MyClass(object):

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

print(self)

obj = MyClass()

obj.firstM()

print(obj)Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

hello, World

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>Verkapselung

Die Kapselung ist eine der Grundlagen von OOP. OOP ermöglicht es uns, die Komplexität der internen Arbeitsweise des Objekts, die für den Entwickler von Vorteil ist, auf folgende Weise zu verbergen:

Vereinfacht und erleichtert das Verständnis der Verwendung eines Objekts ohne Kenntnis der Interna.

Jede Änderung kann leicht verwaltet werden.

Die objektorientierte Programmierung hängt stark von der Kapselung ab. Die Begriffe Kapselung und Abstraktion (auch als Datenverstecken bezeichnet) werden häufig als Synonyme verwendet. Sie sind fast synonym, da die Abstraktion durch Einkapselung erreicht wird.

Die Kapselung bietet uns den Mechanismus, den Zugriff auf einige der Objektkomponenten einzuschränken. Dies bedeutet, dass die interne Darstellung eines Objekts nicht von außerhalb der Objektdefinition gesehen werden kann. Der Zugriff auf diese Daten erfolgt normalerweise über spezielle Methoden -Getters und Setters.

Diese Daten werden in Instanzattributen gespeichert und können von überall außerhalb der Klasse bearbeitet werden. Um dies zu sichern, sollte auf diese Daten nur mit Instanzmethoden zugegriffen werden. Direkter Zugriff sollte nicht gestattet sein.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.age

zack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

45

Fourty FiveDie Daten sollten nur unter Verwendung von Ausnahmebehandlungskonstrukten gespeichert werden, wenn sie korrekt und gültig sind. Wie wir oben sehen können, gibt es keine Einschränkung für die Benutzereingabe der setAge () -Methode. Es kann sich um eine Zeichenfolge, eine Zahl oder eine Liste handeln. Wir müssen also den obigen Code überprüfen, um sicherzustellen, dass er korrekt gespeichert wird.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.agezack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Init Konstruktor

Das __initDie Methode __ wird implizit aufgerufen, sobald ein Objekt einer Klasse instanziiert wird. Dadurch wird das Objekt initialisiert.

x = MyClass()Die oben gezeigte Codezeile erstellt eine neue Instanz und weist dieses Objekt der lokalen Variablen x zu.

Das heißt, die Instanziierungsoperation calling a class object, erstellt ein leeres Objekt. Viele Klassen erstellen gerne Objekte mit Instanzen, die an einen bestimmten Anfangszustand angepasst sind. Daher kann eine Klasse eine spezielle Methode mit dem Namen '__init __ ()' wie gezeigt definieren -

def __init__(self):

self.data = []Python ruft während der Instanziierung __init__ auf, um ein zusätzliches Attribut zu definieren, das auftreten soll, wenn eine Klasse instanziiert wird, die möglicherweise einige Anfangswerte für dieses Objekt einrichtet oder eine für die Instanziierung erforderliche Routine ausführt. In diesem Beispiel kann eine neue, initialisierte Instanz erhalten werden durch -

x = MyClass()Die Methode __init __ () kann für eine größere Flexibilität einzelne oder mehrere Argumente enthalten. Der Init steht für Initialisierung, da er Attribute der Instanz initialisiert. Es wird der Konstruktor einer Klasse genannt.

class myclass(object):

def __init__(self,aaa, bbb):

self.a = aaa

self.b = bbb

x = myclass(4.5, 3)

print(x.a, x.b)Ausgabe

4.5 3Klassenattribute

Das in der Klasse definierte Attribut heißt "Klassenattribute" und die in der Funktion definierten Attribute heißen "Instanzattribute". Während der Definition wird diesen Attributen kein Selbst vorangestellt, da dies die Eigenschaft der Klasse und nicht einer bestimmten Instanz ist.

Auf die Klassenattribute kann sowohl von der Klasse selbst (className.attributeName) als auch von den Instanzen der Klasse (inst.attributeName) zugegriffen werden. Die Instanzen haben also Zugriff sowohl auf das Instanzattribut als auch auf Klassenattribute.

>>> class myclass():

age = 21

>>> myclass.age

21

>>> x = myclass()

>>> x.age

21

>>>Ein Klassenattribut kann in einer Instanz überschrieben werden, obwohl dies keine gute Methode ist, um die Kapselung zu unterbrechen.

In Python gibt es einen Suchpfad für Attribute. Die erste ist die in der Klasse definierte Methode und dann die darüber liegende Klasse.

>>> class myclass(object):

classy = 'class value'

>>> dd = myclass()

>>> print (dd.classy) # This should return the string 'class value'

class value

>>>

>>> dd.classy = "Instance Value"

>>> print(dd.classy) # Return the string "Instance Value"

Instance Value

>>>

>>> # This will delete the value set for 'dd.classy' in the instance.

>>> del dd.classy

>>> >>> # Since the overriding attribute was deleted, this will print 'class

value'.

>>> print(dd.classy)

class value

>>>Wir überschreiben das Klassenattribut 'classy' in der Instanz dd. Wenn es überschrieben wird, liest der Python-Interpreter den überschriebenen Wert. Sobald der neue Wert mit 'del' gelöscht wurde, ist der überschriebene Wert in der Instanz nicht mehr vorhanden, und daher geht die Suche eine Ebene höher und wird von der Klasse abgerufen.

Arbeiten mit Klassen- und Instanzdaten

Lassen Sie uns in diesem Abschnitt verstehen, wie sich die Klassendaten auf die Instanzdaten beziehen. Wir können Daten entweder in einer Klasse oder in einer Instanz speichern. Wenn wir eine Klasse entwerfen, entscheiden wir, welche Daten zur Instanz gehören und welche Daten in der Gesamtklasse gespeichert werden sollen.

Eine Instanz kann auf die Klassendaten zugreifen. Wenn wir mehrere Instanzen erstellen, können diese Instanzen auf ihre einzelnen Attributwerte sowie auf die gesamten Klassendaten zugreifen.

Somit sind Klassendaten die Daten, die von allen Instanzen gemeinsam genutzt werden. Beachten Sie den unten angegebenen Code, um das Verständnis zu verbessern -

class InstanceCounter(object):

count = 0 # class attribute, will be accessible to all instances

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

InstanceCounter.count +=1 # Increment the value of class attribute, accessible through class name

# In above line, class ('InstanceCounter') act as an object

def set_val(self, newval):

self.val = newval

def get_val(self):

return self.val

def get_count(self):

return InstanceCounter.count

a = InstanceCounter(9)

b = InstanceCounter(18)

c = InstanceCounter(27)

for obj in (a, b, c):

print ('val of obj: %s' %(obj.get_val())) # Initialized value ( 9, 18, 27)

print ('count: %s' %(obj.get_count())) # always 3Ausgabe

val of obj: 9

count: 3

val of obj: 18

count: 3

val of obj: 27

count: 3Kurz gesagt, Klassenattribute sind für alle Instanzen der Klasse gleich, während Instanzattribute für jede Instanz spezifisch sind. Für zwei verschiedene Instanzen haben wir zwei verschiedene Instanzattribute.

class myClass:

class_attribute = 99

def class_method(self):

self.instance_attribute = 'I am instance attribute'

print (myClass.__dict__)Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

{'__module__': '__main__', 'class_attribute': 99, 'class_method': <function myClass.class_method at 0x04128D68>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__doc__': None}Das Instanzattribut myClass.__dict__ wie gezeigt -

>>> a = myClass()

>>> a.class_method()

>>> print(a.__dict__)

{'instance_attribute': 'I am instance attribute'}In diesem Kapitel werden verschiedene in Python integrierte Funktionen, Datei-E / A-Operationen und Überladungskonzepte ausführlich beschrieben.

Integrierte Python-Funktionen

Der Python-Interpreter verfügt über eine Reihe von Funktionen, die als integrierte Funktionen bezeichnet werden und zur Verwendung verfügbar sind. In seiner neuesten Version enthält Python 68 integrierte Funktionen, wie in der folgenden Tabelle aufgeführt -

| EINGEBAUTE FUNKTIONEN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs() | dict () | Hilfe() | Mindest() | setattr () |

| alle() | dir () | verhexen() | Nächster() | Scheibe() |

| irgendein() | divmod () | Ich würde() | Objekt() | sortiert () |

| ASCII() | aufzählen() | Eingang() | oct () | statische Methode () |

| Behälter() | eval () | int () | öffnen() | str () |

| bool () | exec () | isinstance () | ord () | Summe() |

| bytearray () | Filter() | issubclass () | pow () | Super() |

| Bytes () | schweben() | iter () | drucken() | Tupel () |

| abrufbar() | Format() | len () | Eigentum() | Art() |

| chr () | frozenset () | Liste() | Angebot() | vars () |

| Klassenmethode () | getattr () | Einheimische () | repr () | Postleitzahl() |

| kompilieren() | Globals () | Karte() | rückgängig gemacht() | __importieren__() |

| Komplex() | hasattr () | max () | runden() | |

| delattr () | hash () | memoryview () | einstellen() | |

In diesem Abschnitt werden einige wichtige Funktionen kurz erläutert.

len () Funktion

Die Funktion len () ermittelt die Länge von Zeichenfolgen, Listen oder Sammlungen. Es gibt die Länge oder Anzahl der Elemente eines Objekts zurück, wobei das Objekt eine Zeichenfolge, eine Liste oder eine Sammlung sein kann.

>>> len(['hello', 9 , 45.0, 24])

4Die Funktion len () funktioniert intern wie list.__len__() oder tuple.__len__(). Beachten Sie daher, dass len () nur für Objekte mit einem __ funktioniertlen__() Methode.

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set1.__len__()

4In der Praxis bevorzugen wir jedoch len() anstatt der __len__() Funktion aus folgenden Gründen -

Es ist effizienter. Und es ist nicht erforderlich, dass eine bestimmte Methode geschrieben wird, um den Zugriff auf spezielle Methoden wie __len__ zu verweigern.

Es ist leicht zu pflegen.

Es unterstützt die Abwärtskompatibilität.

Umgekehrt (seq)

Es gibt den umgekehrten Iterator zurück. seq muss ein Objekt sein, das die Methode __reversed __ () hat oder das Sequenzprotokoll unterstützt (die Methode __len __ () und die Methode __getitem __ ()). Es wird allgemein in verwendetfor Schleifen, wenn wir Elemente von hinten nach vorne durchlaufen möchten.

>>> normal_list = [2, 4, 5, 7, 9]

>>>

>>> class CustomSequence():

def __len__(self):

return 5

def __getitem__(self,index):

return "x{0}".format(index)

>>> class funkyback():

def __reversed__(self):

return 'backwards!'

>>> for seq in normal_list, CustomSequence(), funkyback():

print('\n{}: '.format(seq.__class__.__name__), end="")

for item in reversed(seq):

print(item, end=", ")Die for-Schleife am Ende druckt die umgekehrte Liste einer normalen Liste und Instanzen der beiden benutzerdefinierten Sequenzen. Die Ausgabe zeigt dasreversed() funktioniert bei allen dreien, hat aber bei der Definition sehr unterschiedliche Ergebnisse __reversed__.

Ausgabe

Sie können die folgende Ausgabe beobachten, wenn Sie den oben angegebenen Code ausführen -

list: 9, 7, 5, 4, 2,

CustomSequence: x4, x3, x2, x1, x0,

funkyback: b, a, c, k, w, a, r, d, s, !,Aufzählen

Das enumerate () Die Methode fügt einem Iterable einen Zähler hinzu und gibt das Aufzählungsobjekt zurück.

Die Syntax von enumerate () lautet -

enumerate(iterable, start = 0)Hier das zweite Argument start ist optional und der Index beginnt standardmäßig mit Null (0).

>>> # Enumerate

>>> names = ['Rajesh', 'Rahul', 'Aarav', 'Sahil', 'Trevor']

>>> enumerate(names)

<enumerate object at 0x031D9F80>

>>> list(enumerate(names))

[(0, 'Rajesh'), (1, 'Rahul'), (2, 'Aarav'), (3, 'Sahil'), (4, 'Trevor')]

>>>Damit enumerate()Gibt einen Iterator zurück, der ein Tupel ergibt, das die Anzahl der Elemente in der übergebenen Sequenz zählt. Da der Rückgabewert ein Iterator ist, ist ein direkter Zugriff darauf nicht sehr nützlich. Ein besserer Ansatz für enumerate () besteht darin, die Zählung innerhalb einer for-Schleife zu halten.

>>> for i, n in enumerate(names):

print('Names number: ' + str(i))

print(n)

Names number: 0

Rajesh

Names number: 1

Rahul

Names number: 2

Aarav

Names number: 3

Sahil

Names number: 4

TrevorEs gibt viele andere Funktionen in der Standardbibliothek, und hier ist eine weitere Liste einiger weiter verbreiteter Funktionen -

hasattr, getattr, setattr und delattr, Dadurch können Attribute eines Objekts anhand ihrer Zeichenfolgennamen bearbeitet werden.

all und any, die ein iterierbares Objekt akzeptieren und zurückkehren True wenn alle oder einige der Elemente als wahr bewertet werden.

nzip, Dies nimmt zwei oder mehr Sequenzen und gibt eine neue Sequenz von Tupeln zurück, wobei jedes Tupel einen einzelnen Wert aus jeder Sequenz enthält.

Datei-E / A.

Das Konzept der Dateien ist mit dem Begriff objektorientierte Programmierung verbunden. Python hat die von den Betriebssystemen bereitgestellte Schnittstelle in die Abstraktion eingebunden, die es uns ermöglicht, mit Dateiobjekten zu arbeiten.

Das open()Die integrierte Funktion wird verwendet, um eine Datei zu öffnen und ein Dateiobjekt zurückzugeben. Es ist die am häufigsten verwendete Funktion mit zwei Argumenten -

open(filename, mode)Die Funktion open () ruft zwei Argumente auf, das erste ist der Dateiname und das zweite ist der Modus. Hier kann der Modus "r" für den schreibgeschützten Modus, "w" für das reine Schreiben (eine vorhandene Datei mit demselben Namen wird gelöscht) und "a" die Datei zum Anhängen öffnen. Alle in die Datei geschriebenen Daten werden automatisch hinzugefügt bis zum Ende. 'r +' öffnet die Datei zum Lesen und Schreiben. Der Standardmodus ist schreibgeschützt.

Unter Windows öffnet 'b', das an den Modus angehängt ist, die Datei im Binärmodus, daher gibt es auch Modi wie 'rb', 'wb' und 'r + b'.

>>> text = 'This is the first line'

>>> file = open('datawork','w')

>>> file.write(text)

22

>>> file.close()In einigen Fällen möchten wir nur an die vorhandene Datei anhängen, anstatt sie zu überschreiben, da wir den Wert 'a' als Modusargument angeben können, um sie an das Ende der Datei anzuhängen, anstatt die vorhandene Datei vollständig zu überschreiben Inhalt.

>>> f = open('datawork','a')

>>> text1 = ' This is second line'

>>> f.write(text1)

20

>>> f.close()Sobald eine Datei zum Lesen geöffnet wurde, können wir die Methode read, readline oder readlines aufrufen, um den Inhalt der Datei abzurufen. Die read-Methode gibt den gesamten Inhalt der Datei als str- oder bytes-Objekt zurück, je nachdem, ob das zweite Argument 'b' ist.

Aus Gründen der Lesbarkeit und um zu vermeiden, dass eine große Datei auf einmal gelesen wird, ist es häufig besser, eine for-Schleife direkt für ein Dateiobjekt zu verwenden. Bei Textdateien wird jede Zeile einzeln gelesen, und wir können sie innerhalb des Schleifenkörpers verarbeiten. Für Binärdateien ist es jedoch besser, Datenblöcke mit fester Größe mit der read () -Methode zu lesen und einen Parameter für die maximale Anzahl der zu lesenden Bytes zu übergeben.

>>> f = open('fileone','r+')

>>> f.readline()

'This is the first line. \n'

>>> f.readline()

'This is the second line. \n'Beim Schreiben in eine Datei wird über die Schreibmethode für Dateiobjekte ein Zeichenfolgenobjekt (Bytes für Binärdaten) in die Datei geschrieben. Die Methode writelines akzeptiert eine Folge von Zeichenfolgen und schreibt jeden der iterierten Werte in die Datei. Die Writelines-Methode fügt nach jedem Element in der Sequenz keine neue Zeile an.

Schließlich sollte die Methode close () aufgerufen werden, wenn wir mit dem Lesen oder Schreiben der Datei fertig sind, um sicherzustellen, dass alle gepufferten Schreibvorgänge auf die Festplatte geschrieben werden, dass die Datei ordnungsgemäß bereinigt wurde und dass alle mit der Datei verknüpften Ressourcen wieder freigegeben werden das Betriebssystem. Es ist ein besserer Ansatz, die close () -Methode aufzurufen, aber technisch gesehen geschieht dies automatisch, wenn das Skript vorhanden ist.

Eine Alternative zur Methodenüberladung

Das Überladen von Methoden bezieht sich auf mehrere Methoden mit demselben Namen, die unterschiedliche Sätze von Argumenten akzeptieren.

Bei einer einzelnen Methode oder Funktion können wir die Anzahl der Parameter selbst festlegen. Abhängig von der Funktionsdefinition kann es mit null, eins, zwei oder mehr Parametern aufgerufen werden.

class Human:

def sayHello(self, name = None):

if name is not None:

print('Hello ' + name)

else:

print('Hello ')

#Create Instance

obj = Human()

#Call the method, else part will be executed

obj.sayHello()

#Call the method with a parameter, if part will be executed

obj.sayHello('Rahul')Ausgabe

Hello

Hello RahulStandardargumente

Funktionen sind auch Objekte

Ein aufrufbares Objekt ist ein Objekt, das einige Argumente akzeptieren kann und möglicherweise ein Objekt zurückgibt. Eine Funktion ist das einfachste aufrufbare Objekt in Python, aber es gibt auch andere wie Klassen oder bestimmte Klasseninstanzen.

Jede Funktion in einem Python ist ein Objekt. Objekte können Methoden oder Funktionen enthalten, aber Objekt ist keine Funktion erforderlich.

def my_func():

print('My function was called')

my_func.description = 'A silly function'

def second_func():

print('Second function was called')

second_func.description = 'One more sillier function'

def another_func(func):

print("The description:", end=" ")

print(func.description)

print('The name: ', end=' ')

print(func.__name__)

print('The class:', end=' ')

print(func.__class__)

print("Now I'll call the function passed in")

func()

another_func(my_func)

another_func(second_func)Im obigen Code können wir zwei verschiedene Funktionen als Argument an unsere dritte Funktion übergeben und für jede unterschiedliche Ausgabe erhalten -

The description: A silly function

The name: my_func

The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in My function was called The description: One more sillier function The name: second_func The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in Second function was called

callable objects

Just as functions are objects that can have attributes set on them, it is possible to create an object that can be called as though it were a function.

In Python any object with a __call__() method can be called using function-call syntax.

Inheritance and Polymorphism

Inheritance and polymorphism – this is a very important concept in Python. You must understand it better if you want to learn.

Inheritance

One of the major advantages of Object Oriented Programming is re-use. Inheritance is one of the mechanisms to achieve the same. Inheritance allows programmer to create a general or a base class first and then later extend it to more specialized class. It allows programmer to write better code.

Using inheritance you can use or inherit all the data fields and methods available in your base class. Later you can add you own methods and data fields, thus inheritance provides a way to organize code, rather than rewriting it from scratch.

In object-oriented terminology when class X extend class Y, then Y is called super/parent/base class and X is called subclass/child/derived class. One point to note here is that only data fields and method which are not private are accessible by child classes. Private data fields and methods are accessible only inside the class.

syntax to create a derived class is −

class BaseClass:

Body of base class

class DerivedClass(BaseClass):

Body of derived class

Inheriting Attributes

Now look at the below example −

Output

We first created a class called Date and pass the object as an argument, here-object is built-in class provided by Python. Later we created another class called time and called the Date class as an argument. Through this call we get access to all the data and attributes of Date class into the Time class. Because of that when we try to get the get_date method from the Time class object tm we created earlier possible.

Object.Attribute Lookup Hierarchy

- The instance

- The class

- Any class from which this class inherits

Inheritance Examples

Let’s take a closure look into the inheritance example −

Let’s create couple of classes to participate in examples −

- Animal − Class simulate an animal

- Cat − Subclass of Animal

- Dog − Subclass of Animal

In Python, constructor of class used to create an object (instance), and assign the value for the attributes.

Constructor of subclasses always called to a constructor of parent class to initialize value for the attributes in the parent class, then it start assign value for its attributes.

Output

In the above example, we see the command attributes or methods we put in the parent class so that all subclasses or child classes will inherits that property from the parent class.

If a subclass try to inherits methods or data from another subclass then it will through an error as we see when Dog class try to call swatstring() methods from that cat class, it throws an error(like AttributeError in our case).

Polymorphism (“MANY SHAPES”)

Polymorphism is an important feature of class definition in Python that is utilized when you have commonly named methods across classes or subclasses. This permits functions to use entities of different types at different times. So, it provides flexibility and loose coupling so that code can be extended and easily maintained over time.

This allows functions to use objects of any of these polymorphic classes without needing to be aware of distinctions across the classes.

Polymorphism can be carried out through inheritance, with subclasses making use of base class methods or overriding them.

Let understand the concept of polymorphism with our previous inheritance example and add one common method called show_affection in both subclasses −

From the example we can see, it refers to a design in which object of dissimilar type can be treated in the same manner or more specifically two or more classes with method of the same name or common interface because same method(show_affection in below example) is called with either type of objects.

Output

So, all animals show affections (show_affection), but they do differently. The “show_affection” behaviors is thus polymorphic in the sense that it acted differently depending on the animal. So, the abstract “animal” concept does not actually “show_affection”, but specific animals(like dogs and cats) have a concrete implementation of the action “show_affection”.

Python itself have classes that are polymorphic. Example, the len() function can be used with multiple objects and all return the correct output based on the input parameter.

Overriding

In Python, when a subclass contains a method that overrides a method of the superclass, you can also call the superclass method by calling

Super(Subclass, self).method instead of self.method.

Example

class Thought(object):

def __init__(self):

pass

def message(self):

print("Thought, always come and go")

class Advice(Thought):

def __init__(self):

super(Advice, self).__init__()

def message(self):

print('Warning: Risk is always involved when you are dealing with market!')

Inheriting the Constructor

If we see from our previous inheritance example, __init__ was located in the parent class in the up ‘cause the child class dog or cat didn’t‘ve __init__ method in it. Python used the inheritance attribute lookup to find __init__ in animal class. When we created the child class, first it will look the __init__ method in the dog class, then it didn’t find it then looked into parent class Animal and found there and called that there. So as our class design became complex we may wish to initialize a instance firstly processing it through parent class constructor and then through child class constructor.

Output

In above example- all animals have a name and all dogs a particular breed. We called parent class constructor with super. So dog has its own __init__ but the first thing that happen is we call super. Super is built in function and it is designed to relate a class to its super class or its parent class.

In this case we saying that get the super class of dog and pass the dog instance to whatever method we say here the constructor __init__. So in another words we are calling parent class Animal __init__ with the dog object. You may ask why we won’t just say Animal __init__ with the dog instance, we could do this but if the name of animal class were to change, sometime in the future. What if we wanna rearrange the class hierarchy,so the dog inherited from another class. Using super in this case allows us to keep things modular and easy to change and maintain.

So in this example we are able to combine general __init__ functionality with more specific functionality. This gives us opportunity to separate common functionality from the specific functionality which can eliminate code duplication and relate class to one another in a way that reflects the system overall design.

Conclusion

__init__ is like any other method; it can be inherited

If a class does not have a __init__ constructor, Python will check its parent class to see if it can find one.

As soon as it finds one, Python calls it and stops looking

We can use the super () function to call methods in the parent class.

We may want to initialize in the parent as well as our own class.

Multiple Inheritance and the Lookup Tree

As its name indicates, multiple inheritance is Python is when a class inherits from multiple classes.

For example, a child inherits personality traits from both parents (Mother and Father).

Python Multiple Inheritance Syntax

To make a class inherits from multiple parents classes, we write the the names of these classes inside the parentheses to the derived class while defining it. We separate these names with comma.

Below is an example of that −

>>> class Mother:

pass

>>> class Father:

pass

>>> class Child(Mother, Father):

pass

>>> issubclass(Child, Mother) and issubclass(Child, Father)

True

Multiple inheritance refers to the ability of inheriting from two or more than two class. The complexity arises as child inherits from parent and parents inherits from the grandparent class. Python climbs an inheriting tree looking for attributes that is being requested to be read from an object. It will check the in the instance, within class then parent class and lastly from the grandparent class. Now the question arises in what order the classes will be searched - breath-first or depth-first. By default, Python goes with the depth-first.

That’s is why in the below diagram the Python searches the dothis() method first in class A. So the method resolution order in the below example will be

Mro- D→B→A→C

Look at the below multiple inheritance diagram −

Let’s go through an example to understand the “mro” feature of an Python.

Output

Example 3

Let’s take another example of “diamond shape” multiple inheritance.

Above diagram will be considered ambiguous. From our previous example understanding “method resolution order” .i.e. mro will be D→B→A→C→A but it’s not. On getting the second A from the C, Python will ignore the previous A. so the mro will be in this case will be D→B→C→A.

Let’s create an example based on above diagram −

Output

Simple rule to understand the above output is- if the same class appear in the method resolution order, the earlier appearances of this class will be remove from the method resolution order.

In conclusion −

Any class can inherit from multiple classes

Python normally uses a “depth-first” order when searching inheriting classes.

But when two classes inherit from the same class, Python eliminates the first appearances of that class from the mro.

Decorators, Static and Class Methods

Functions(or methods) are created by def statement.

Though methods works in exactly the same way as a function except one point where method first argument is instance object.

We can classify methods based on how they behave, like

Simple method − defined outside of a class. This function can access class attributes by feeding instance argument:

def outside_func(():

Instance method −

def func(self,)

Class method − if we need to use class attributes

@classmethod

def cfunc(cls,)

Static method − do not have any info about the class

@staticmethod

def sfoo()

Till now we have seen the instance method, now is the time to get some insight into the other two methods,

Class Method

The @classmethod decorator, is a builtin function decorator that gets passed the class it was called on or the class of the instance it was called on as first argument. The result of that evaluation shadows your function definition.

syntax

class C(object):

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

....

fun: function that needs to be converted into a class method

returns: a class method for function

They have the access to this cls argument, it can’t modify object instance state. That would require access to self.

It is bound to the class and not the object of the class.

Class methods can still modify class state that applies across all instances of the class.

Static Method

A static method takes neither a self nor a cls(class) parameter but it’s free to accept an arbitrary number of other parameters.

syntax

class C(object):

@staticmethod

def fun(arg1, arg2, ...):

...

returns: a static method for function funself.

- A static method can neither modify object state nor class state.

- They are restricted in what data they can access.

When to use what

We generally use class method to create factory methods. Factory methods return class object (similar to a constructor) for different use cases.

We generally use static methods to create utility functions.

Python Design Pattern

Overview

Modern software development needs to address complex business requirements. It also needs to take into account factors such as future extensibility and maintainability. A good design of a software system is vital to accomplish these goals. Design patterns play an important role in such systems.

To understand design pattern, let’s consider below example −

Every car’s design follows a basic design pattern, four wheels, steering wheel, the core drive system like accelerator-break-clutch, etc.

So, all things repeatedly built/ produced, shall inevitably follow a pattern in its design.. it cars, bicycle, pizza, atm machines, whatever…even your sofa bed.

Designs that have almost become standard way of coding some logic/mechanism/technique in software, hence come to be known as or studied as, Software Design Patterns.

Why is Design Pattern Important?

Benefits of using Design Patterns are −

Helps you to solve common design problems through a proven approach.

No ambiguity in the understanding as they are well documented.

Reduce the overall development time.

Helps you deal with future extensions and modifications with more ease than otherwise.

May reduce errors in the system since they are proven solutions to common problems.

Classification of Design Patterns

The GoF (Gang of Four) design patterns are classified into three categories namely creational, structural and behavioral.

Creational Patterns

Creational design patterns separate the object creation logic from the rest of the system. Instead of you creating objects, creational patterns creates them for you. The creational patterns include Abstract Factory, Builder, Factory Method, Prototype and Singleton.

Creational Patterns are not commonly used in Python because of the dynamic nature of the language. Also language itself provide us with all the flexibility we need to create in a sufficient elegant fashion, we rarely need to implement anything on top, like singleton or Factory.

Also these patterns provide a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using a new operator.

Structural Patterns

Sometimes instead of starting from scratch, you need to build larger structures by using an existing set of classes. That’s where structural class patterns use inheritance to build a new structure. Structural object patterns use composition/ aggregation to obtain a new functionality. Adapter, Bridge, Composite, Decorator, Façade, Flyweight and Proxy are Structural Patterns. They offers best ways to organize class hierarchy.

Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral patterns offers best ways of handling communication between objects. Patterns comes under this categories are: Visitor, Chain of responsibility, Command, Interpreter, Iterator, Mediator, Memento, Observer, State, Strategy and Template method are Behavioral Patterns.

Because they represent the behavior of a system, they are used generally to describe the functionality of software systems.

Commonly used Design Patterns

Singleton

It is one of the most controversial and famous of all design patterns. It is used in overly object-oriented languages, and is a vital part of traditional object-oriented programming.

The Singleton pattern is used for,

When logging needs to be implemented. The logger instance is shared by all the components of the system.

The configuration files is using this because cache of information needs to be maintained and shared by all the various components in the system.

Managing a connection to a database.

Here is the UML diagram,

class Logger(object):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if not hasattr(cls, '_logger'):

cls._logger = super(Logger, cls).__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs)

return cls._logger

In this example, Logger is a Singleton.

When __new__ is called, it normally constructs a new instance of that class. When we override it, we first check if our singleton instance has been created or not. If not, we create it using a super call. Thus, whenever we call the constructor on Logger, we always get the exact same instance.

>>>

>>> obj1 = Logger()

>>> obj2 = Logger()

>>> obj1 == obj2

True

>>>

>>> obj1

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

>>> obj2

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

Object Oriented Python - Advanced Features

In this we will look into some of the advanced features which Python provide

Core Syntax in our Class design

In this we will look onto, how Python allows us to take advantage of operators in our classes. Python is largely objects and methods call on objects and this even goes on even when its hidden by some convenient syntax.

>>> var1 = 'Hello'

>>> var2 = ' World!'

>>> var1 + var2

'Hello World!'

>>>

>>> var1.__add__(var2)

'Hello World!'

>>> num1 = 45

>>> num2 = 60

>>> num1.__add__(num2)

105

>>> var3 = ['a', 'b']

>>> var4 = ['hello', ' John']

>>> var3.__add__(var4)

['a', 'b', 'hello', ' John']

So if we have to add magic method __add__ to our own classes, could we do that too. Let’s try to do that.

We have a class called Sumlist which has a contructor __init__ which takes list as an argument called my_list.

class SumList(object):

def __init__(self, my_list):

self.mylist = my_list

def __add__(self, other):

new_list = [ x + y for x, y in zip(self.mylist, other.mylist)]

return SumList(new_list)

def __repr__(self):

return str(self.mylist)

aa = SumList([3,6, 9, 12, 15])

bb = SumList([100, 200, 300, 400, 500])

cc = aa + bb # aa.__add__(bb)

print(cc) # should gives us a list ([103, 206, 309, 412, 515])

Output

[103, 206, 309, 412, 515]

But there are many methods which are internally managed by others magic methods. Below are some of them,

'abc' in var # var.__contains__('abc')

var == 'abc' # var.__eq__('abc')

var[1] # var.__getitem__(1)

var[1:3] # var.__getslice__(1, 3)

len(var) # var.__len__()

print(var) # var.__repr__()

Inheriting From built-in types

Classes can also inherit from built-in types this means inherits from any built-in and take advantage of all the functionality found there.

In below example we are inheriting from dictionary but then we are implementing one of its method __setitem__. This (setitem) is invoked when we set key and value in the dictionary. As this is a magic method, this will be called implicitly.

class MyDict(dict):

def __setitem__(self, key, val):