Python zorientowany obiektowo - szybki przewodnik

Języki programowania pojawiają się nieustannie, podobnie jak różne metodologie. Jedną z metod, która stała się dość popularna w ciągu ostatnich kilku lat, jest programowanie obiektowe.

W tym rozdziale omówiono cechy języka programowania Python, które sprawiają, że jest to język programowania obiektowego.

Schemat klasyfikacji programowania języków

Python można scharakteryzować za pomocą metodologii programowania obiektowego. Poniższy obraz przedstawia charakterystykę różnych języków programowania. Obserwuj cechy Pythona, które sprawiają, że jest on zorientowany obiektowo.

| Zajęcia Langauage | Kategorie | Langauages |

|---|---|---|

| Paradygmat programowania | Proceduralny | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go |

| Skrypty | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby | |

| Funkcjonalny | Clojure, Eralang, Haskell, Scala | |

| Klasa kompilacji | Statyczny | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, java, Go, Haskell, Scala |

| Dynamiczny | CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Php, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang | |

| Klasa typu | Silny | C #, java, Go, Python, Ruby, Clojure, Erlang, Haskell, Scala |

| Słaby | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C, CoffeeScript, JavaScript, Perl, Php | |

| Klasa pamięci | Zarządzane | Inni |

| Niezarządzane | C, C ++, C #, Objective-C |

Co to jest programowanie obiektowe?

Object Orientedśrodki skierowane na przedmioty. Innymi słowy, oznacza to funkcjonalnie ukierunkowane na modelowanie obiektów. Jest to jedna z wielu technik używanych do modelowania złożonych systemów poprzez opisywanie zbioru obiektów oddziałujących na podstawie ich danych i zachowania.

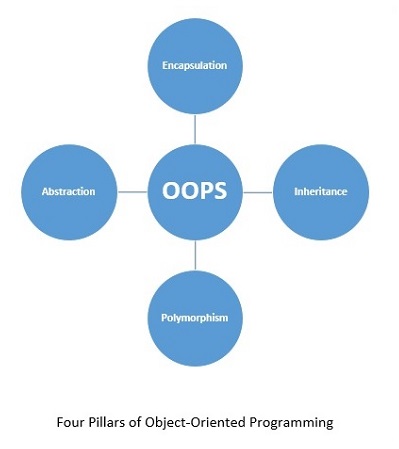

Python, programowanie zorientowane obiektowo (OOP), to sposób programowania, który koncentruje się na używaniu obiektów i klas do projektowania i budowania aplikacji. Główne filary programowania obiektowego (OOP) to Inheritance, Polymorphism, Abstraction, ogłoszenie Encapsulation.

Analiza zorientowana obiektowo (OOA) to proces badania problemu, systemu lub zadania oraz identyfikacja obiektów i interakcji między nimi.

Dlaczego warto wybrać programowanie obiektowe?

Python został zaprojektowany z podejściem obiektowym. OOP oferuje następujące korzyści -

Zapewnia przejrzystą strukturę programu, która ułatwia mapowanie rzeczywistych problemów i ich rozwiązań.

Ułatwia konserwację i modyfikację istniejącego kodu.

Zwiększa modułowość programu, ponieważ każdy obiekt istnieje niezależnie, a nowe funkcje można łatwo dodawać bez zakłócania istniejących.

Przedstawia dobre ramy dla bibliotek kodu, w których dostarczane komponenty mogą być łatwo dostosowywane i modyfikowane przez programistę.

Zapewnia możliwość ponownego wykorzystania kodu

Programowanie proceduralne a programowanie obiektowe

Programowanie proceduralne wywodzi się z programowania strukturalnego opartego na koncepcjach functions/procedure/routines. Dostęp do danych i ich zmiana jest łatwa w programowaniu zorientowanym proceduralnie. Z drugiej strony programowanie zorientowane obiektowo (OOP) umożliwia dekompozycję problemu na kilka jednostek nazywanychobjectsa następnie zbuduj dane i funkcje wokół tych obiektów. Koncentruje się bardziej na danych niż na procedurze lub funkcjach. Również w przypadku OOP dane są ukryte i nie można uzyskać do nich dostępu za pomocą procedury zewnętrznej.

Tabela na poniższej ilustracji przedstawia główne różnice między podejściem POP i OOP.

Różnica między programowaniem proceduralnym (POP) a programem. Programowanie obiektowe (OOP).

| Programowanie proceduralne | Programowanie zorientowane na obiekt | |

|---|---|---|

| Oparte na | W Pop cały nacisk kładzie się na dane i funkcje | Ups opiera się na prawdziwym scenariuszu. Cały program jest podzielony na małe części zwane obiektami |

| Możliwość ponownego użycia | Ograniczone ponowne wykorzystanie kodu | Ponowne wykorzystanie kodu |

| Podejście | Podejście odgórne | Projektowanie ukierunkowane na obiekt |

| Specyfikatory dostępu | Żaden | Publiczne, prywatne i chronione |

| Przenoszenie danych | Dane mogą swobodnie przenosić się z funkcji do funkcji w systemie | W Oops dane mogą się przenosić i komunikować ze sobą za pomocą funkcji składowych |

| Dostęp do danych | W popie większość funkcji wykorzystuje globalne dane do udostępniania, do których można uzyskać swobodny dostęp z funkcji do funkcji w systemie | W Ups dane nie mogą swobodnie przenosić się z metody na metodę, można je przechowywać publicznie lub prywatnie, abyśmy mogli kontrolować dostęp do danych |

| Ukrywanie danych | W popie, tak specyficzny sposób na ukrywanie danych, więc trochę mniej bezpieczny | Zapewnia ukrywanie danych, o wiele bezpieczniejsze |

| Przeciążenie | Niemożliwe | Funkcje i przeciążanie operatorów |

| Języki przykładowe | C, VB, Fortran, Pascal | C ++, Python, Java, C # |

| Abstrakcja | Używa abstrakcji na poziomie procedury | Używa abstrakcji na poziomie klasy i obiektu |

Zasady programowania obiektowego

Programowanie obiektowe (OOP) opiera się na koncepcji objects zamiast działań i datazamiast logiki. Aby język programowania był zorientowany obiektowo, powinien posiadać mechanizm umożliwiający pracę z klasami i obiektami, a także implementację i stosowanie podstawowych zasad i pojęć obiektowych, a mianowicie dziedziczenie, abstrakcję, hermetyzację i polimorfizm.

Rozumiemy w skrócie każdy z filarów programowania obiektowego -

Kapsułkowanie

Ta właściwość ukrywa niepotrzebne szczegóły i ułatwia zarządzanie strukturą programu. Implementacja i stan każdego obiektu są ukryte za dobrze określonymi granicami, co zapewnia przejrzysty i prosty interfejs do pracy z nimi. Jednym ze sposobów osiągnięcia tego jest uczynienie danych prywatnymi.

Dziedzictwo

Dziedziczenie, zwane także uogólnieniem, pozwala nam uchwycić hierarchiczną relację między klasami i obiektami. Na przykład „owoc” jest uogólnieniem słowa „pomarańcza”. Dziedziczenie jest bardzo przydatne z punktu widzenia ponownego wykorzystania kodu.

Abstrakcja

Ta właściwość pozwala nam ukryć szczegóły i wyeksponować tylko istotne cechy koncepcji lub przedmiotu. Na przykład osoba prowadząca skuter wie, że po naciśnięciu klaksonu emitowany jest dźwięk, ale nie ma pojęcia, w jaki sposób jest on generowany po naciśnięciu klaksonu.

Wielopostaciowość

Polimorfizm oznacza wiele form. Oznacza to, że rzecz lub działanie występuje w różnych formach lub na różne sposoby. Dobrym przykładem polimorfizmu jest przeciążanie konstruktorów w klasach.

Python zorientowany obiektowo

Sercem programowania w Pythonie jest object i OOPjednak nie musisz ograniczać się do korzystania z OOP, organizując swój kod w klasy. OOP dodaje do całej filozofii projektowania Pythona i zachęca do czystego i pragmatycznego sposobu programowania. OOP umożliwia także pisanie większych i złożonych programów.

Moduły a klasy i obiekty

Moduły są jak „Słowniki”

Podczas pracy z modułami zwróć uwagę na następujące punkty -

Moduł Pythona to pakiet służący do hermetyzacji kodu wielokrotnego użytku.

Moduły znajdują się w folderze z rozszerzeniem __init__.py plik na nim.

Moduły zawierają funkcje i klasy.

Moduły są importowane przy użyciu rozszerzenia import słowo kluczowe.

Przypomnij sobie, że słownik to key-valuepara. To znaczy, jeśli masz słownik z kluczemEmployeID i chcesz go odzyskać, będziesz musiał użyć następujących linii kodu -

employee = {“EmployeID”: “Employee Unique Identity!”}

print (employee [‘EmployeID])Będziesz musiał pracować nad modułami z następującym procesem -

Moduł to plik Pythona zawierający pewne funkcje lub zmienne.

Zaimportuj potrzebny plik.

Teraz możesz uzyskać dostęp do funkcji lub zmiennych w tym module za pomocą „.” (dot) Operator.

Rozważmy moduł o nazwie employee.py z funkcją o nazwie employee. Kod funkcji podano poniżej -

# this goes in employee.py

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)Teraz zaimportuj moduł, a następnie uzyskaj dostęp do funkcji EmployeID -

import employee

employee. EmployeID()Możesz wstawić do niego zmienną o nazwie Age, jak pokazano -

def EmployeID():

print (“Employee Unique Identity!”)

# just a variable

Age = “Employee age is **”Teraz uzyskaj dostęp do tej zmiennej w następujący sposób -

import employee

employee.EmployeID()

print(employee.Age)Teraz porównajmy to ze słownikiem -

Employee[‘EmployeID’] # get EmployeID from employee

Employee.employeID() # get employeID from the module

Employee.Age # get access to variableZauważ, że w Pythonie istnieje wspólny wzorzec -

Zrób key = value styl kontenera

Wyciągnij coś z tego przez nazwę klucza

Porównując moduł ze słownikiem, oba są podobne, z wyjątkiem następujących -

W przypadku dictionary, klucz jest łańcuchem, a składnia to [klucz].

W przypadku module, klucz jest identyfikatorem, a składnia to .key.

Klasy są jak moduły

Moduł to wyspecjalizowany słownik, który może przechowywać kod Pythona, dzięki czemu można się do niego dostać za pomocą znaku „.” Operator. Klasa to sposób na zgrupowanie funkcji i danych i umieszczenie ich w kontenerze, aby można było uzyskać do nich dostęp za pomocą operatora „.”.

Jeśli musisz stworzyć klasę podobną do modułu pracownika, możesz to zrobić za pomocą następującego kodu -

class employee(object):

def __init__(self):

self. Age = “Employee Age is ##”

def EmployeID(self):

print (“This is just employee unique identity”)Note- Klasy są preferowane w stosunku do modułów, ponieważ można je ponownie wykorzystać bez większych zakłóceń. Podczas gdy z modułami masz tylko jeden z całym programem.

Obiekty są jak mini-import

Klasa jest jak mini-module i możesz importować w podobny sposób, jak robisz to w przypadku klas, używając pojęcia o nazwie instantiate. Pamiętaj, że podczas tworzenia wystąpienia klasy otrzymasz plikobject.

Możesz utworzyć instancję obiektu, podobnie jak wywołanie klasy takiej jak funkcja, jak pokazano -

this_obj = employee() # Instantiatethis_obj.EmployeID() # get EmployeId from the class

print(this_obj.Age) # get variable AgeMożesz to zrobić na jeden z trzech następujących sposobów -

# dictionary style

Employee[‘EmployeID’]

# module style

Employee.EmployeID()

Print(employee.Age)

# Class style

this_obj = employee()

this_obj.employeID()

Print(this_obj.Age)W tym rozdziale wyjaśniono szczegółowo konfigurowanie środowiska Python na komputerze lokalnym.

Wymagania wstępne i zestawy narzędzi

Zanim przejdziesz do dalszej nauki języka Python, sugerujemy sprawdzenie, czy spełnione są następujące wymagania wstępne -

Najnowsza wersja Pythona jest zainstalowana na Twoim komputerze

Zainstalowano IDE lub edytor tekstu

Masz podstawową znajomość pisania i debugowania w Pythonie, to znaczy możesz wykonać następujące czynności w Pythonie -

Potrafi pisać i uruchamiać programy w języku Python.

Debuguj programy i diagnozuj błędy.

Pracuj z podstawowymi typami danych.

pisać for pętle, while pętle i if sprawozdania

Kod functions

Jeśli nie masz doświadczenia z językiem programowania, możesz znaleźć wiele samouczków dla początkujących w Pythonie na

https://www.tutorialpoints.com/Instalowanie Pythona

Poniższe kroki szczegółowo pokazują, jak zainstalować Python na komputerze lokalnym -

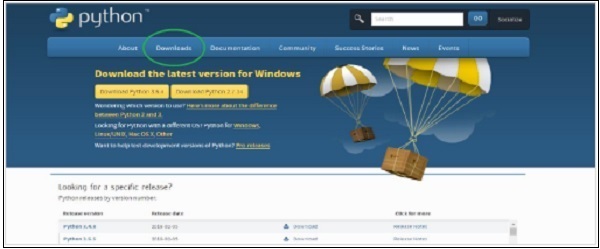

Step 1 - Wejdź na oficjalną stronę Pythona https://www.python.org/, Kliknij na Downloads menu i wybierz najnowszą lub dowolną stabilną wersję do wyboru.

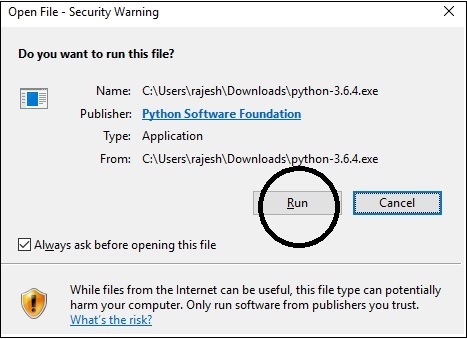

Step 2- Zapisz pobrany plik instalatora Pythona, a po pobraniu otwórz go. KliknijRun i wybierz Next opcja domyślna i zakończ instalację.

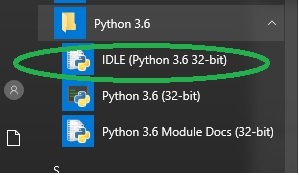

Step 3- Po zainstalowaniu powinieneś zobaczyć menu Pythona, jak pokazano na poniższym obrazku. Uruchom program, wybierając IDLE (Python GUI).

Spowoduje to uruchomienie powłoki Pythona. Wpisz proste polecenia, aby sprawdzić instalację.

Wybór IDE

Zintegrowane środowisko programistyczne to edytor tekstu nastawiony na tworzenie oprogramowania. Będziesz musiał zainstalować IDE, aby kontrolować przepływ swojego programowania i grupować projekty podczas pracy w Pythonie. Oto kilka IDE dostępnych online. Możesz wybrać jeden w dogodnym dla siebie czasie.

- Pycharm IDE

- Komodo IDE

- Eric Python IDE

Note - Eclipse IDE jest najczęściej używane w Javie, jednak ma wtyczkę Python.

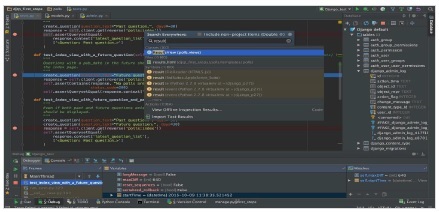

Pycharm

Pycharm, wieloplatformowe IDE jest jednym z najpopularniejszych obecnie dostępnych IDE. Zapewnia pomoc w kodowaniu i analizę wraz z uzupełnianiem kodu, nawigacją po projekcie i kodzie, zintegrowanym testowaniem jednostkowym, integracją kontroli wersji, debugowaniem i wieloma innymi

Link do pobrania

https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/download/#section=windowsLanguages Supported - Python, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Coffee Script, TypeScript, Cython, AngularJS, Node.js, języki szablonów.

Zrzut ekranu

Dlaczego wybrać?

PyCharm oferuje swoim użytkownikom następujące funkcje i korzyści -

- Wieloplatformowe IDE zgodne z systemami Windows, Linux i Mac OS

- Obejmuje Django IDE oraz obsługę CSS i JavaScript

- Zawiera tysiące wtyczek, zintegrowany terminal i kontrolę wersji

- Integruje się z Git, SVN i Mercurial

- Oferuje inteligentne narzędzia do edycji dla Pythona

- Łatwa integracja z Virtualenv, Docker i Vagrant

- Prosta nawigacja i funkcje wyszukiwania

- Analiza i refaktoryzacja kodu

- Konfigurowalne wtryski

- Obsługuje mnóstwo bibliotek Pythona

- Zawiera szablony i debugery JavaScript

- Obejmuje debuggery Python / Django

- Działa z Google App Engine, dodatkowymi frameworkami i bibliotekami.

- Posiada konfigurowalny interfejs użytkownika, dostępna emulacja VIM

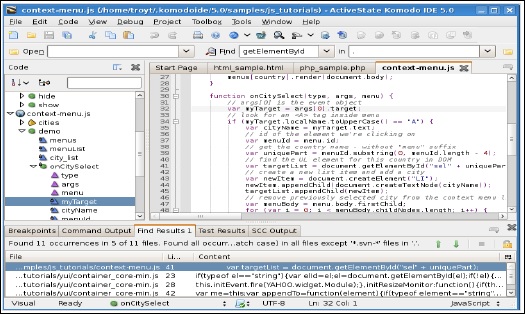

Komodo IDE

Jest to poliglotowe IDE, które obsługuje ponad 100 języków i zasadniczo dla języków dynamicznych, takich jak Python, PHP i Ruby. Jest to komercyjne IDE dostępne przez 21 dni za darmo z pełną funkcjonalnością. ActiveState to firma programistyczna zarządzająca rozwojem środowiska Komodo IDE. Oferuje również skróconą wersję Komodo znaną jako Komodo Edit do prostych zadań programistycznych.

To IDE zawiera wszystkie rodzaje funkcji, od poziomu podstawowego do zaawansowanego. Jeśli jesteś studentem lub wolnym strzelcem, możesz go kupić za prawie połowę rzeczywistej ceny. Jednak jest to całkowicie bezpłatne dla nauczycieli i profesorów z uznanych instytucji i uniwersytetów.

Posiada wszystkie funkcje potrzebne do tworzenia aplikacji internetowych i mobilnych, w tym obsługę wszystkich języków i platform.

Link do pobrania

Linki do pobrania dla Komodo Edit (wersja bezpłatna) i Komodo IDE (wersja płatna) są podane tutaj -

Komodo Edit (free)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-editKomodo IDE (paid)

https://www.activestate.com/komodo-ide/downloads/ideZrzut ekranu

Dlaczego wybrać?

- Potężne IDE z obsługą Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby i wiele innych.

- IDE dla wielu platform.

Zawiera podstawowe funkcje, takie jak zintegrowana obsługa debuggera, automatyczne uzupełnianie, przeglądarka Document Object Model (DOM), przeglądarka kodu, interaktywne powłoki, konfiguracja punktów przerwania, profilowanie kodu, zintegrowane testowanie jednostkowe. Krótko mówiąc, jest to profesjonalne środowisko IDE z wieloma funkcjami zwiększającymi produktywność.

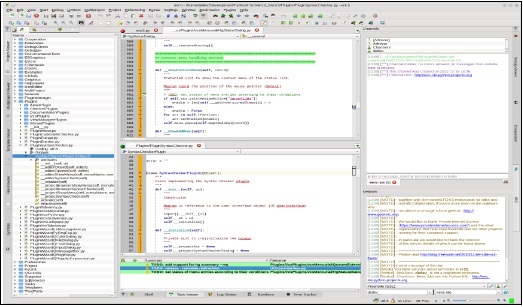

Eric Python IDE

Jest to IDE typu open source dla języków Python i Ruby. Eric to w pełni funkcjonalny edytor i IDE, napisane w Pythonie. Opiera się na wieloplatformowym zestawie narzędzi Qt GUI, integrującym wysoce elastyczną kontrolę edytora Scintilla. IDE jest bardzo konfigurowalne i można wybrać, czego używać, a czego nie. Możesz pobrać Eric IDE z poniższego linku:

https://eric-ide.python-projects.org/eric-download.htmlDlaczego warto wybrać

- Świetne wcięcie, podświetlanie błędów.

- Pomoc dotycząca kodu

- Uzupełnianie kodu

- Czyszczenie kodu za pomocą PyLint

- Szybkie wyszukiwanie

- Zintegrowany debugger Pythona.

Zrzut ekranu

Wybór edytora tekstu

Nie zawsze możesz potrzebować IDE. W przypadku zadań, takich jak nauka programowania w Pythonie lub Arduino, lub podczas pracy nad szybkim skryptem w skrypcie powłoki, który pomaga zautomatyzować niektóre zadania, wystarczy prosty i lekki edytor tekstu ukierunkowany na kod. Również wiele edytorów tekstu oferuje funkcje, takie jak podświetlanie składni i wykonywanie skryptów w programie, podobnie jak w IDE. Oto niektóre z edytorów tekstu -

- Atom

- Wysublimowany tekst

- Notepad++

Edytor tekstu Atom

Atom to edytor tekstu, który można zhakować, stworzony przez zespół GitHub. Jest to darmowy edytor tekstu i kodu typu open source, co oznacza, że cały kod jest dostępny do czytania, modyfikowania na własny użytek, a nawet wprowadzania ulepszeń. Jest to wieloplatformowy edytor tekstu kompatybilny z systemami macOS, Linux i Microsoft Windows z obsługą wtyczek napisanych w Node.js i osadzonym Git Control.

Link do pobrania

https://atom.io/Zrzut ekranu

Obsługiwane języki

C / C ++, C #, CSS, CoffeeScript, HTML, JavaScript, Java, JSON, Julia, Objective-C, PHP, Perl, Python, Ruby on Rails, Ruby, Shell script, Scala, SQL, XML, YAML i wiele innych.

Wysublimowany edytor tekstu

Sublime text jest oprogramowaniem zastrzeżonym i oferuje bezpłatną wersję próbną, aby przetestować go przed zakupem. Według stackoverflow.com jest to czwarte najpopularniejsze środowisko programistyczne.

Niektóre z zalet, które zapewnia, to niesamowita szybkość, łatwość użycia i wsparcie społeczności. Obsługuje również wiele języków programowania i języków znaczników, a użytkownicy mogą dodawać funkcje za pomocą wtyczek, zwykle tworzonych przez społeczność i utrzymywanych na podstawie licencji wolnego oprogramowania.

Zrzut ekranu

Obsługiwany język

- Python, Ruby, JavaScript itp.

Dlaczego wybrać?

Dostosuj przypisania klawiszy, menu, fragmenty, makra, uzupełnienia i nie tylko.

Funkcja automatycznego uzupełniania

- Szybkie wstawianie tekstu i kodu za pomocą wysublimowanych fragmentów tekstu za pomocą skrawków, znaczników pól i znaczników miejsca

Szybko się otwiera

Obsługa wielu platform dla systemów Mac, Linux i Windows.

Przesuń kursor w miejsce, w które chcesz się udać

Wybierz wiele wierszy, słów i kolumn

Notepad ++

Jest to darmowy edytor kodu źródłowego i zamiennik Notatnika, który obsługuje kilka języków od Assembly do XML, w tym Python. Działa w środowisku MS Windows, a jego użytkowanie podlega licencji GPL. Oprócz podświetlania składni Notepad ++ ma kilka funkcji, które są szczególnie przydatne dla programistów.

Zrzut ekranu

Kluczowe cechy

- Podświetlanie składni i składanie składni

- PCRE (wyrażenie regularne zgodne z Perlem) Wyszukaj / zamień

- Całkowicie konfigurowalny GUI

- Automatyczne zakończenie

- Edycja na kartach

- Multi-View

- Środowisko wielojęzyczne

- Do uruchomienia z różnymi argumentami

Obsługiwany język

- Prawie każdy język (ponad 60 języków), jak Python, C, C ++, C #, Java itp.

Struktury danych Pythona są bardzo intuicyjne z punktu widzenia składni i oferują duży wybór operacji. Musisz wybrać strukturę danych Pythona w zależności od tego, czego dotyczą dane, czy wymagają modyfikacji, czy są to dane stałe i wymagany typ dostępu, np. Na początku / końcu / losowo itp.

Listy

Lista reprezentuje najbardziej wszechstronny typ struktury danych w Pythonie. Lista jest kontenerem zawierającym wartości oddzielone przecinkami (elementy lub elementy) między nawiasami kwadratowymi. Listy są pomocne, gdy chcemy pracować z wieloma powiązanymi wartościami. Ponieważ listy przechowują dane razem, możemy wykonywać te same metody i operacje na wielu wartościach jednocześnie. Indeksy list zaczynają się od zera iw przeciwieństwie do łańcuchów, listy są zmienne.

Struktura danych - lista

>>>

>>> # Any Empty List

>>> empty_list = []

>>>

>>> # A list of String

>>> str_list = ['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> # A list of Integers

>>> int_list = [1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>>

>>> #Mixed items list

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>> # To print the list

>>>

>>> print(empty_list)

[]

>>> print(str_list)

['Life', 'Is', 'Beautiful']

>>> print(type(str_list))

<class 'list'>

>>> print(int_list)

[1, 4, 5, 9, 18]

>>> print(mixed_list)

['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']Dostęp do elementów na liście Pythona

Każda pozycja listy ma przypisany numer - czyli indeks lub pozycję tego numeru. Indeksowanie zawsze zaczyna się od zera, drugi indeks to jedynka i tak dalej. Aby uzyskać dostęp do elementów listy, możemy użyć tych numerów indeksu w nawiasach kwadratowych. Obserwuj następujący kod, na przykład -

>>> mixed_list = ['This', 9, 'is', 18, 45.9, 'a', 54, 'mixed', 99, 'list']

>>>

>>> # To access the First Item of the list

>>> mixed_list[0]

'This'

>>> # To access the 4th item

>>> mixed_list[3]

18

>>> # To access the last item of the list

>>> mixed_list[-1]

'list'Puste obiekty

Puste obiekty to najprostsze i najbardziej podstawowe typy wbudowane w Pythonie. Używaliśmy ich wielokrotnie, nie zauważając, i rozszerzyliśmy je na każdą stworzoną przez nas klasę. Głównym celem napisania pustej klasy jest zablokowanie czegoś na jakiś czas, a następnie rozszerzenie i dodanie do tego zachowania.

Dodanie zachowania do klasy oznacza zastąpienie struktury danych obiektem i zmianę wszystkich odniesień do niego. Dlatego ważne jest, aby sprawdzić dane, czy są to zamaskowany obiekt, zanim cokolwiek stworzysz. Obserwuj następujący kod, aby lepiej zrozumieć:

>>> #Empty objects

>>>

>>> obj = object()

>>> obj.x = 9

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

obj.x = 9

AttributeError: 'object' object has no attribute 'x'Więc z góry widzimy, że nie jest możliwe ustawienie żadnych atrybutów na obiekcie, który został utworzony bezpośrednio. Gdy Python pozwala obiektowi mieć dowolne atrybuty, potrzeba pewnej ilości pamięci systemowej, aby śledzić, jakie atrybuty ma każdy obiekt, do przechowywania zarówno nazwy atrybutu, jak i jego wartości. Nawet jeśli nie są przechowywane żadne atrybuty, pewna ilość pamięci jest przydzielana na potencjalne nowe atrybuty.

Dlatego Python domyślnie wyłącza dowolne właściwości obiektu i kilka innych funkcji wbudowanych.

>>> # Empty Objects

>>>

>>> class EmpObject:

pass

>>> obj = EmpObject()

>>> obj.x = 'Hello, World!'

>>> obj.x

'Hello, World!'Dlatego jeśli chcemy zgrupować właściwości razem, moglibyśmy przechowywać je w pustym obiekcie, jak pokazano w powyższym kodzie. Jednak ta metoda nie zawsze jest sugerowana. Pamiętaj, że klas i obiektów należy używać tylko wtedy, gdy chcesz określić zarówno dane, jak i zachowania.

Krotki

Krotki są podobne do list i mogą przechowywać elementy. Są jednak niezmienne, więc nie możemy dodawać, usuwać ani zastępować obiektów. Podstawowe korzyści, jakie krotka zapewnia ze względu na jej niezmienność, to fakt, że możemy ich używać jako kluczy w słownikach lub w innych lokalizacjach, w których obiekt wymaga wartości skrótu.

Krotki służą do przechowywania danych, a nie zachowania. Jeśli potrzebujesz zachowania do manipulowania krotką, musisz przekazać krotkę do funkcji (lub metody na innym obiekcie), która wykonuje akcję.

Ponieważ krotka może działać jako klucz słownikowy, przechowywane wartości różnią się od siebie. Możemy utworzyć krotkę, oddzielając wartości przecinkami. Krotki są umieszczone w nawiasach, ale nie są obowiązkowe. Poniższy kod przedstawia dwa identyczne przypisania.

>>> stock1 = 'MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45

>>> stock2 = ('MSFT', 95.00, 97.45, 92.45)

>>> type (stock1)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> type(stock2)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> stock1 == stock2

True

>>>Definiowanie krotki

Krotki są bardzo podobne do list, z tym wyjątkiem, że cały zestaw elementów jest ujęty w nawiasy zamiast w kwadratowe.

Podobnie jak w przypadku wycinania listy, otrzymujesz nową listę, a kiedy dzielisz krotkę, otrzymujesz nową krotkę.

>>> tupl = ('Tuple','is', 'an','IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl[0]

'Tuple'

>>> tupl[-1]

'list'

>>> tupl[1:3]

('is', 'an')Metody krotki w Pythonie

Poniższy kod przedstawia metody w krotkach Pythona -

>>> tupl

('Tuple', 'is', 'an', 'IMMUTABLE', 'list')

>>> tupl.append('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#148>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.append('new')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

>>> tupl.remove('is')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#149>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.remove('is')

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'remove'

>>> tupl.index('list')

4

>>> tupl.index('new')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#151>", line 1, in <module>

tupl.index('new')

ValueError: tuple.index(x): x not in tuple

>>> "is" in tupl

True

>>> tupl.count('is')

1Z powyższego kodu możemy zrozumieć, że krotki są niezmienne, a zatem -

ty cannot dodać elementy do krotki.

ty cannot dołączyć lub rozszerzyć metodę.

ty cannot usunąć elementy z krotki.

Krotki mają no usuń lub wyskocz metodę.

Count i index to metody dostępne w krotce.

Słownik

Słownik jest jednym z wbudowanych typów danych Pythona i definiuje relacje jeden do jednego między kluczami i wartościami.

Definiowanie słowników

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby zrozumieć, jak definiować słownik -

>>> # empty dictionary

>>> my_dict = {}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with integer keys

>>> my_dict = { 1:'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>>

>>> # dictionary with mixed keys

>>> my_dict = {'name': 'Aarav', 1: [ 2, 4, 10]}

>>>

>>> # using built-in function dict()

>>> my_dict = dict({1:'msft', 2:'IT'})

>>>

>>> # From sequence having each item as a pair

>>> my_dict = dict([(1,'msft'), (2,'IT')])

>>>

>>> # Accessing elements of a dictionary

>>> my_dict[1]

'msft'

>>> my_dict[2]

'IT'

>>> my_dict['IT']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#177>", line 1, in <module>

my_dict['IT']

KeyError: 'IT'

>>>Z powyższego kodu możemy zauważyć, że:

Najpierw tworzymy słownik z dwoma elementami i przypisujemy go do zmiennej my_dict. Każdy element jest parą klucz-wartość, a cały zestaw elementów jest ujęty w nawiasy klamrowe.

Numer 1 jest kluczem i msftjest jego wartością. Podobnie,2 jest kluczem i IT jest jego wartością.

Możesz uzyskać wartości według klucza, ale nie odwrotnie. Tak więc, kiedy próbujemymy_dict[‘IT’] , zgłasza wyjątek, ponieważ IT nie jest kluczem.

Modyfikowanie słowników

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby zrozumieć, jak modyfikować słownik -

>>> # Modifying a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'IT'}

>>> my_dict[2] = 'Software'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software'}

>>>

>>> my_dict[3] = 'Microsoft Technologies'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}Z powyższego kodu możemy zauważyć, że -

Nie możesz mieć zduplikowanych kluczy w słowniku. Zmiana wartości istniejącego klucza spowoduje usunięcie starej wartości.

W dowolnym momencie możesz dodać nowe pary klucz-wartość.

Słowniki nie mają pojęcia porządku między elementami. Są to proste kolekcje nieuporządkowane.

Mieszanie typów danych w słowniku

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby zrozumieć mieszanie typów danych w słowniku -

>>> # Mixing Data Types in a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies'}

>>> my_dict[4] = 'Operating System'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>> my_dict['Bill Gates'] = 'Owner'

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}Z powyższego kodu możemy zauważyć, że -

Nie tylko łańcuchy, ale wartość słownika może mieć dowolny typ danych, w tym łańcuchy, liczby całkowite, w tym sam słownik.

W przeciwieństwie do wartości słownikowych, klucze słownika są bardziej ograniczone, ale mogą być dowolnego typu, na przykład łańcuchami, liczbami całkowitymi lub innymi.

Usuwanie elementów ze słowników

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby dowiedzieć się, jak usuwać elementy ze słownika -

>>> # Deleting Items from a Dictionary

>>>

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System',

'Bill Gates': 'Owner'}

>>>

>>> del my_dict['Bill Gates']

>>> my_dict

{1: 'msft', 2: 'Software', 3: 'Microsoft Technologies', 4: 'Operating System'}

>>>

>>> my_dict.clear()

>>> my_dict

{}Z powyższego kodu możemy zauważyć, że -

del - umożliwia usuwanie pojedynczych pozycji ze słownika za pomocą klawisza.

clear - usuwa wszystkie pozycje ze słownika.

Zestawy

Set () to nieuporządkowana kolekcja bez zduplikowanych elementów. Chociaż poszczególne elementy są niezmienne, sam zestaw jest zmienny, czyli możemy dodawać lub usuwać elementy / przedmioty z zestawu. Możemy wykonywać operacje matematyczne, takie jak suma, przecięcie itp. Ze zbiorem.

Chociaż ogólnie zestawy można zaimplementować za pomocą drzew, ustawione w Pythonie można zaimplementować za pomocą tabeli skrótów. Pozwala to na wysoce zoptymalizowaną metodę sprawdzania, czy określony element znajduje się w zestawie

Tworzenie zestawu

Zestaw powstaje poprzez umieszczenie wszystkich elementów (elementów) w nawiasach klamrowych {}, oddzielone przecinkiem lub za pomocą funkcji wbudowanej set(). Obserwuj następujące wiersze kodu -

>>> #set of integers

>>> my_set = {1,2,4,8}

>>> print(my_set)

{8, 1, 2, 4}

>>>

>>> #set of mixed datatypes

>>> my_set = {1.0, "Hello World!", (2, 4, 6)}

>>> print(my_set)

{1.0, (2, 4, 6), 'Hello World!'}

>>>Metody dla zestawów

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby zrozumieć metody dla zestawów -

>>> >>> #METHODS FOR SETS

>>>

>>> #add(x) Method

>>> topics = {'Python', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>> topics.add('C++')

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>>

>>> #union(s) Method, returns a union of two set.

>>> topics

{'C#', 'C++', 'Java', 'Python'}

>>> team = {'Developer', 'Content Writer', 'Editor','Tester'}

>>> group = topics.union(team)

>>> group

{'Tester', 'C#', 'Python', 'Editor', 'Developer', 'C++', 'Java', 'Content

Writer'}

>>> # intersets(s) method, returns an intersection of two sets

>>> inters = topics.intersection(team)

>>> inters

set()

>>>

>>> # difference(s) Method, returns a set containing all the elements of

invoking set but not of the second set.

>>>

>>> safe = topics.difference(team)

>>> safe

{'Python', 'C++', 'Java', 'C#'}

>>>

>>> diff = topics.difference(group)

>>> diff

set()

>>> #clear() Method, Empties the whole set.

>>> group.clear()

>>> group

set()

>>>Operatory dla zbiorów

Obserwuj poniższy kod, aby zrozumieć operatory dla zestawów -

>>> # PYTHON SET OPERATIONS

>>>

>>> #Creating two sets

>>> set1 = set()

>>> set2 = set()

>>>

>>> # Adding elements to set

>>> for i in range(1,5):

set1.add(i)

>>> for j in range(4,9):

set2.add(j)

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set2

{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Union of set1 and set2

>>> set3 = set1 | set2 # same as set1.union(set2)

>>> print('Union of set1 & set2: set3 = ', set3)

Union of set1 & set2: set3 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> #Intersection of set1 & set2

>>> set4 = set1 & set2 # same as set1.intersection(set2)

>>> print('Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = ', set4)

Intersection of set1 and set2: set4 = {4}

>>>

>>> # Checking relation between set3 and set4

>>> if set3 > set4: # set3.issuperset(set4)

print('Set3 is superset of set4')

elif set3 < set4: #set3.issubset(set4)

print('Set3 is subset of set4')

else: #set3 == set4

print('Set 3 is same as set4')

Set3 is superset of set4

>>>

>>> # Difference between set3 and set4

>>> set5 = set3 - set4

>>> print('Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = ', set5)

Elements in set3 and not in set4: set5 = {1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}

>>>

>>> # Check if set4 and set5 are disjoint sets

>>> if set4.isdisjoint(set5):

print('Set4 and set5 have nothing in common\n')

Set4 and set5 have nothing in common

>>> # Removing all the values of set5

>>> set5.clear()

>>> set5 set()W tym rozdziale omówimy szczegółowo terminy zorientowane obiektowo i koncepcje programowania. Klasa to tylko przykład fabryki. Ta fabryka zawiera plan, który opisuje, jak tworzyć instancje. Instancje lub obiekt są konstruowane z klasy. W większości przypadków możemy mieć więcej niż jedno wystąpienie klasy. Każda instancja ma zestaw atrybutów, a te atrybuty są zdefiniowane w klasie, więc oczekuje się, że każda instancja określonej klasy będzie miała te same atrybuty.

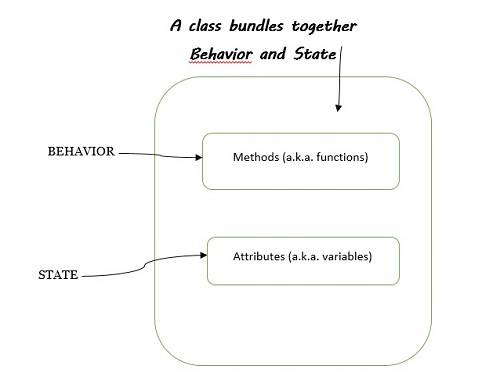

Pakiety klas: zachowanie i stan

Klasa pozwoli ci połączyć zachowanie i stan obiektu. Aby lepiej zrozumieć, zapoznaj się z poniższym diagramem -

Podczas omawiania pakietów klas warto zwrócić uwagę na następujące punkty:

Słowo behavior jest identyczny z function - jest to fragment kodu, który coś robi (lub implementuje zachowanie)

Słowo state jest identyczny z variables - jest to miejsce do przechowywania wartości w klasie.

Kiedy razem potwierdzamy zachowanie i stan klasy, oznacza to, że klasa pakuje funkcje i zmienne.

Klasy mają metody i atrybuty

W Pythonie tworzenie metody definiuje zachowanie klasy. Metoda słowa to nazwa OOP nadana funkcji zdefiniowanej w klasie. Podsumowując -

Class functions - jest synonimem methods

Class variables - jest synonimem name attributes.

Class - plan instancji z dokładnym zachowaniem.

Object - jedna z instancji klasy, wykonuje funkcje zdefiniowane w klasie.

Type - wskazuje klasę, do której należy instancja

Attribute - Dowolna wartość obiektu: object.attribute

Method - „atrybut wywoływalny” zdefiniowany w klasie

Przyjrzyj się na przykład poniższemu fragmentowi kodu -

var = “Hello, John”

print( type (var)) # < type ‘str’> or <class 'str'>

print(var.upper()) # upper() method is called, HELLO, JOHNTworzenie i tworzenie instancji

Poniższy kod pokazuje, jak utworzyć naszą pierwszą klasę, a następnie jej wystąpienie.

class MyClass(object):

pass

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj)Tutaj stworzyliśmy klasę o nazwie MyClassi który nie spełnia żadnego zadania. Argumentobject w MyClass class obejmuje dziedziczenie klas i zostanie omówione w dalszych rozdziałach. pass w powyższym kodzie wskazuje, że ten blok jest pusty, czyli jest to pusta definicja klasy.

Stwórzmy instancję this_obj z MyClass() klasę i wydrukuj jak pokazano -

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x03B08E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x0369D390>Tutaj utworzyliśmy instancję MyClass.Kod szesnastkowy odnosi się do adresu, pod którym przechowywany jest obiekt. Inna instancja wskazuje na inny adres.

Teraz zdefiniujmy jedną zmienną wewnątrz klasy MyClass() i pobierz zmienną z instancji tej klasy, jak pokazano w poniższym kodzie -

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

# Create first instance of MyClass

this_obj = MyClass()

print(this_obj.var)

# Another instance of MyClass

that_obj = MyClass()

print (that_obj.var)Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

9

9Ponieważ instancja wie, z której klasy jest tworzona, więc gdy żąda się atrybutu z instancji, szuka ona atrybutu i klasy. Nazywa się toattribute lookup.

Metody instancji

Funkcja zdefiniowana w klasie nazywa się a method.Metoda instancji wymaga instancji, aby ją wywołać i nie wymaga dekoratora. Podczas tworzenia metody instancji pierwszym parametrem jest zawszeself. Chociaż możemy to nazwać (self) pod jakąkolwiek inną nazwą, zaleca się używanie self, ponieważ jest to konwencja nazewnictwa.

class MyClass(object):

var = 9

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

obj = MyClass()

print(obj.var)

obj.firstM()Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

9

hello, WorldZauważ, że w powyższym programie zdefiniowaliśmy metodę z self jako argumentem. Ale nie możemy wywołać metody, ponieważ nie zadeklarowaliśmy dla niej żadnego argumentu.

class MyClass(object):

def firstM(self):

print("hello, World")

print(self)

obj = MyClass()

obj.firstM()

print(obj)Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

hello, World

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>

<__main__.MyClass object at 0x036A8E10>Kapsułkowanie

Hermetyzacja jest jedną z podstaw OOP. OOP pozwala nam ukryć złożoność wewnętrznego działania obiektu, co jest korzystne dla dewelopera w następujący sposób -

Upraszcza i ułatwia zrozumienie korzystania z obiektu bez znajomości wewnętrznych elementów.

Każda zmiana może być łatwa do opanowania.

Programowanie zorientowane obiektowo w dużej mierze polega na hermetyzacji. Terminy enkapsulacja i abstrakcja (zwane także ukrywaniem danych) są często używane jako synonimy. Są prawie synonimami, ponieważ abstrakcję osiąga się poprzez hermetyzację.

Hermetyzacja zapewnia nam mechanizm ograniczania dostępu do niektórych komponentów obiektu, co oznacza, że wewnętrzna reprezentacja obiektu nie jest widoczna spoza definicji obiektu. Dostęp do tych danych uzyskuje się zwykle za pomocą specjalnych metod -Getters i Setters.

Te dane są przechowywane w atrybutach instancji i można nimi manipulować z dowolnego miejsca poza klasą. Aby to zabezpieczyć, dostęp do tych danych powinien być możliwy tylko przy użyciu metod instancji. Nie należy zezwalać na bezpośredni dostęp.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.age

zack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

45

Fourty FiveDane powinny być przechowywane tylko wtedy, gdy są poprawne i prawidłowe, przy użyciu konstrukcji obsługi wyjątków. Jak widać powyżej, nie ma ograniczeń co do danych wejściowych użytkownika do metody setAge (). Może to być ciąg, liczba lub lista. Musimy więc sprawdzić powyższy kod, aby upewnić się, że jest on przechowywany.

class MyClass(object):

def setAge(self, num):

self.age = num

def getAge(self):

return self.agezack = MyClass()

zack.setAge(45)

print(zack.getAge())

zack.setAge("Fourty Five")

print(zack.getAge())Init Constructor

__init__ jest wywoływana niejawnie zaraz po utworzeniu instancji obiektu klasy, co spowoduje zainicjowanie obiektu.

x = MyClass()Linia kodu pokazana powyżej utworzy nową instancję i przypisze ten obiekt do lokalnej zmiennej x.

To znaczy operacja tworzenia instancji calling a class object, tworzy pusty obiekt. Wiele klas lubi tworzyć obiekty z instancjami dostosowanymi do określonego stanu początkowego. Dlatego klasa może zdefiniować specjalną metodę o nazwie „__init __ ()”, jak pokazano -

def __init__(self):

self.data = []Python wywołuje __init__ podczas tworzenia instancji, aby zdefiniować dodatkowy atrybut, który powinien wystąpić podczas tworzenia instancji klasy. Może to być konfigurowanie niektórych wartości początkowych dla tego obiektu lub uruchamianie procedury wymaganej podczas tworzenia instancji. W tym przykładzie nową, zainicjowaną instancję można uzyskać przez -

x = MyClass()Metoda __init __ () może mieć jeden lub wiele argumentów dla większej elastyczności. Init oznacza inicjalizację, ponieważ inicjalizuje atrybuty instancji. Nazywa się konstruktorem klasy.

class myclass(object):

def __init__(self,aaa, bbb):

self.a = aaa

self.b = bbb

x = myclass(4.5, 3)

print(x.a, x.b)Wynik

4.5 3Atrybuty klas

Atrybut zdefiniowany w klasie nazywa się „atrybutami klasy”, a atrybuty zdefiniowane w funkcji - „atrybutami instancji”. Podczas definiowania atrybuty te nie są poprzedzane przedrostkiem self, ponieważ są one własnością klasy, a nie konkretnej instancji.

Dostęp do atrybutów klasy można uzyskać za pośrednictwem samej klasy (nazwaKlasy.nazwa_atrybutu), a także instancji tej klasy (nazwa instancji). Zatem instancje mają dostęp zarówno do atrybutu instancji, jak i atrybutów klas.

>>> class myclass():

age = 21

>>> myclass.age

21

>>> x = myclass()

>>> x.age

21

>>>Atrybut klasy można przesłonić w instancji, nawet jeśli nie jest to dobra metoda przerywania hermetyzacji.

W Pythonie istnieje ścieżka wyszukiwania atrybutów. Pierwsza to metoda zdefiniowana w klasie, a następnie klasa nad nią.

>>> class myclass(object):

classy = 'class value'

>>> dd = myclass()

>>> print (dd.classy) # This should return the string 'class value'

class value

>>>

>>> dd.classy = "Instance Value"

>>> print(dd.classy) # Return the string "Instance Value"

Instance Value

>>>

>>> # This will delete the value set for 'dd.classy' in the instance.

>>> del dd.classy

>>> >>> # Since the overriding attribute was deleted, this will print 'class

value'.

>>> print(dd.classy)

class value

>>>Zastępujemy atrybut klasy „classy” w instancji dd. Kiedy jest zastępowany, interpreter Pythona odczytuje zastąpioną wartość. Ale gdy nowa wartość zostanie usunięta za pomocą „del”, nadpisana wartość nie jest już obecna w instancji, a zatem wyszukiwanie przechodzi o poziom wyżej i pobiera ją z klasy.

Praca z danymi klas i instancji

W tej sekcji wyjaśnijmy, jak dane klasy odnoszą się do danych instancji. Możemy przechowywać dane w klasie lub w instancji. Projektując klasę, decydujemy, które dane należą do instancji, a które powinny być przechowywane w całej klasie.

Instancja może uzyskać dostęp do danych klasy. Jeśli utworzymy wiele instancji, wtedy te instancje będą miały dostęp do swoich indywidualnych wartości atrybutów, a także do ogólnych danych klas.

Zatem dane klasy to dane, które są współużytkowane przez wszystkie instancje. Przestrzegaj kodu podanego poniżej, aby lepiej rozpoznać -

class InstanceCounter(object):

count = 0 # class attribute, will be accessible to all instances

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

InstanceCounter.count +=1 # Increment the value of class attribute, accessible through class name

# In above line, class ('InstanceCounter') act as an object

def set_val(self, newval):

self.val = newval

def get_val(self):

return self.val

def get_count(self):

return InstanceCounter.count

a = InstanceCounter(9)

b = InstanceCounter(18)

c = InstanceCounter(27)

for obj in (a, b, c):

print ('val of obj: %s' %(obj.get_val())) # Initialized value ( 9, 18, 27)

print ('count: %s' %(obj.get_count())) # always 3Wynik

val of obj: 9

count: 3

val of obj: 18

count: 3

val of obj: 27

count: 3Krótko mówiąc, atrybuty klas są takie same dla wszystkich instancji klasy, podczas gdy atrybuty instancji są specyficzne dla każdej instancji. Dla dwóch różnych instancji będziemy mieć dwa różne atrybuty instancji.

class myClass:

class_attribute = 99

def class_method(self):

self.instance_attribute = 'I am instance attribute'

print (myClass.__dict__)Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

{'__module__': '__main__', 'class_attribute': 99, 'class_method': <function myClass.class_method at 0x04128D68>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'myClass' objects>, '__doc__': None}Atrybut instancji myClass.__dict__ jak pokazano -

>>> a = myClass()

>>> a.class_method()

>>> print(a.__dict__)

{'instance_attribute': 'I am instance attribute'}W tym rozdziale omówiono szczegółowo różne funkcje wbudowane w Pythonie, operacje we / wy na plikach i koncepcje przeciążania.

Funkcje wbudowane w Pythonie

Interpreter Pythona ma wiele funkcji nazywanych funkcjami wbudowanymi, które są łatwo dostępne do użycia. W swojej najnowszej wersji Python zawiera 68 wbudowanych funkcji wymienionych w poniższej tabeli -

| WBUDOWANE FUNKCJE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abs () | dict () | Wsparcie() | min () | setattr () |

| wszystko() | reż () | klątwa() | Kolejny() | plasterek() |

| każdy() | divmod () | ID() | obiekt() | posortowane () |

| ascii () | wyliczać() | Wejście() | paź () | staticmethod () |

| kosz() | eval () | int () | otwarty() | str () |

| bool () | exec () | isinstance () | ord () | suma() |

| bytearray () | filtr() | issubclass () | pow () | Wspaniały() |

| bajty () | pływak() | iter () | wydrukować() | krotka () |

| wywoływany () | format() | len () | własność() | rodzaj() |

| chr () | Frozenset () | lista() | zasięg() | vars () |

| classmethod () | getattr () | miejscowi () | repr () | zamek błyskawiczny() |

| skompilować() | globale () | mapa() | wywrócony() | __import__() |

| złożony() | hasattr () | max () | okrągły() | |

| delattr () | haszysz() | Widok pamięciowy() | zestaw() | |

W tej sekcji omówiono pokrótce niektóre z ważnych funkcji -

funkcja len ()

Funkcja len () pobiera długość łańcuchów, listy lub kolekcji. Zwraca długość lub liczbę elementów obiektu, gdzie obiekt może być łańcuchem, listą lub kolekcją.

>>> len(['hello', 9 , 45.0, 24])

4Funkcja len () działa wewnętrznie jak list.__len__() lub tuple.__len__(). W związku z tym zwróć uwagę, że len () działa tylko na obiektach, które mają znak __len__() metoda.

>>> set1

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> set1.__len__()

4Jednak w praktyce wolimy len() zamiast tego __len__() działają z następujących powodów -

Jest bardziej wydajna. I nie jest konieczne, aby określona metoda była napisana w celu odmowy dostępu do metod specjalnych, takich jak __len__.

Jest łatwy w utrzymaniu.

Obsługuje kompatybilność wsteczną.

Reversed (seq)

Zwraca iterator odwrotny. seq musi być obiektem, który ma metodę __reversed __ () lub obsługuje protokół sekwencji (metodę __len __ () i metodę __getitem __ ()). Jest zwykle używany wfor pętle, gdy chcemy zapętlić elementy od tyłu do przodu.

>>> normal_list = [2, 4, 5, 7, 9]

>>>

>>> class CustomSequence():

def __len__(self):

return 5

def __getitem__(self,index):

return "x{0}".format(index)

>>> class funkyback():

def __reversed__(self):

return 'backwards!'

>>> for seq in normal_list, CustomSequence(), funkyback():

print('\n{}: '.format(seq.__class__.__name__), end="")

for item in reversed(seq):

print(item, end=", ")Pętla for na końcu wypisuje odwróconą listę normalnej listy oraz wystąpienia dwóch niestandardowych sekwencji. Dane wyjściowe to pokazująreversed() działa na wszystkich trzech z nich, ale daje bardzo różne wyniki, kiedy je definiujemy __reversed__.

Wynik

Po wykonaniu powyższego kodu można zaobserwować następujące dane wyjściowe -

list: 9, 7, 5, 4, 2,

CustomSequence: x4, x3, x2, x1, x0,

funkyback: b, a, c, k, w, a, r, d, s, !,Wyliczać

Plik enumerate () metoda dodaje licznik do iterowalnej i zwraca obiekt wyliczeniowy.

Składnia enumerate () to -

enumerate(iterable, start = 0)Tutaj drugi argument start jest opcjonalny i domyślnie indeks zaczyna się od zera (0).

>>> # Enumerate

>>> names = ['Rajesh', 'Rahul', 'Aarav', 'Sahil', 'Trevor']

>>> enumerate(names)

<enumerate object at 0x031D9F80>

>>> list(enumerate(names))

[(0, 'Rajesh'), (1, 'Rahul'), (2, 'Aarav'), (3, 'Sahil'), (4, 'Trevor')]

>>>Więc enumerate()zwraca iterator, który zwraca krotkę, która przechowuje liczbę elementów w przekazanej sekwencji. Ponieważ wartość zwracana jest iteratorem, bezpośredni dostęp do niej nie jest zbyt przydatny. Lepszym podejściem do enumerate () jest utrzymywanie count w pętli for.

>>> for i, n in enumerate(names):

print('Names number: ' + str(i))

print(n)

Names number: 0

Rajesh

Names number: 1

Rahul

Names number: 2

Aarav

Names number: 3

Sahil

Names number: 4

TrevorW bibliotece standardowej znajduje się wiele innych funkcji, a oto kolejna lista bardziej powszechnie używanych funkcji -

hasattr, getattr, setattr i delattr, co pozwala na manipulowanie atrybutami obiektu za pomocą ich nazw łańcuchowych.

all i any, które akceptują iterowalny obiekt i zwracają True jeśli wszystkie lub jakiekolwiek elementy zostaną ocenione jako prawdziwe.

nzip, który przyjmuje dwie lub więcej sekwencji i zwraca nową sekwencję krotek, gdzie każda krotka zawiera jedną wartość z każdej sekwencji.

We / wy pliku

Pojęcie plików jest związane z terminem programowania obiektowego. Python opakował interfejs udostępniany przez systemy operacyjne w sposób abstrakcyjny, co pozwala nam pracować z obiektami plików.

Plik open()wbudowana funkcja służy do otwierania pliku i zwracania obiektu pliku. Jest to najczęściej używana funkcja z dwoma argumentami -

open(filename, mode)Funkcja open () wywołuje dwa argumenty, pierwszy to nazwa pliku, a drugi to tryb. Tutaj trybem może być „r” dla trybu tylko do odczytu, „w” dla samego zapisu (istniejący plik o tej samej nazwie zostanie usunięty), a „a” otwiera plik do dołączenia, wszelkie dane zapisane w pliku są automatycznie dodawane do końca. „r +” otwiera plik do odczytu i zapisu. Domyślnym trybem jest tylko do odczytu.

W systemie Windows, „b” dołączone do trybu otwiera plik w trybie binarnym, więc są też tryby takie jak „rb”, „wb” i „r + b”.

>>> text = 'This is the first line'

>>> file = open('datawork','w')

>>> file.write(text)

22

>>> file.close()W niektórych przypadkach chcemy po prostu dopisać do istniejącego pliku zamiast go nadpisywać, w tym celu moglibyśmy podać wartość 'a' jako argument trybu, aby dołączyć do końca pliku, zamiast całkowicie nadpisywać istniejący plik zawartość.

>>> f = open('datawork','a')

>>> text1 = ' This is second line'

>>> f.write(text1)

20

>>> f.close()Po otwarciu pliku do odczytu możemy wywołać metodę read, readline lub readlines, aby pobrać zawartość pliku. Metoda read zwraca całą zawartość pliku jako obiekt str lub bajtów, w zależności od tego, czy drugi argument to „b”.

Aby zapewnić czytelność i uniknąć odczytywania dużego pliku za jednym razem, często lepiej jest użyć pętli for bezpośrednio na obiekcie pliku. W przypadku plików tekstowych odczyta każdą linię, pojedynczo i możemy przetworzyć ją wewnątrz ciała pętli. Jednak w przypadku plików binarnych lepiej jest odczytywać fragmenty danych o stałej wielkości przy użyciu metody read (), przekazując parametr określający maksymalną liczbę bajtów do odczytania.

>>> f = open('fileone','r+')

>>> f.readline()

'This is the first line. \n'

>>> f.readline()

'This is the second line. \n'Zapis do pliku, poprzez metodę write na obiektach pliku, zapisze obiekt typu string (bajty dla danych binarnych) do pliku. Metoda writelines akceptuje sekwencję ciągów i zapisuje każdą z iterowanych wartości do pliku. Metoda writelines nie dodaje nowego wiersza po każdym elemencie w sekwencji.

Na koniec należy wywołać metodę close (), gdy skończymy odczytywać lub zapisywać plik, aby upewnić się, że wszelkie buforowane zapisy są zapisywane na dysku, plik został odpowiednio wyczyszczony i że wszystkie zasoby powiązane z plikiem są z powrotem system operacyjny. Lepszym podejściem jest wywołanie metody close (), ale technicznie rzecz biorąc, nastąpi to automatycznie, gdy skrypt istnieje.

Alternatywa dla przeciążania metod

Przeciążanie metod odnosi się do posiadania wielu metod o tej samej nazwie, które akceptują różne zestawy argumentów.

Mając jedną metodę lub funkcję, możemy sami określić liczbę parametrów. W zależności od definicji funkcji można ją wywołać z zerem, jednym, dwoma lub więcej parametrami.

class Human:

def sayHello(self, name = None):

if name is not None:

print('Hello ' + name)

else:

print('Hello ')

#Create Instance

obj = Human()

#Call the method, else part will be executed

obj.sayHello()

#Call the method with a parameter, if part will be executed

obj.sayHello('Rahul')Wynik

Hello

Hello RahulArgumenty domyślne

Funkcje też są obiektami

Obiekt wywoływalny to obiekt, który może przyjmować pewne argumenty i prawdopodobnie zwróci obiekt. Funkcja jest najprostszym wywoływalnym obiektem w Pythonie, ale są też inne, takie jak klasy lub niektóre instancje klas.

Każda funkcja w Pythonie jest obiektem. Obiekty mogą zawierać metody lub funkcje, ale obiekt nie jest funkcją.

def my_func():

print('My function was called')

my_func.description = 'A silly function'

def second_func():

print('Second function was called')

second_func.description = 'One more sillier function'

def another_func(func):

print("The description:", end=" ")

print(func.description)

print('The name: ', end=' ')

print(func.__name__)

print('The class:', end=' ')

print(func.__class__)

print("Now I'll call the function passed in")

func()

another_func(my_func)

another_func(second_func)W powyższym kodzie jesteśmy w stanie przekazać dwie różne funkcje jako argument do naszej trzeciej funkcji i uzyskać różne dane wyjściowe dla każdej z nich -

The description: A silly function

The name: my_func

The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in My function was called The description: One more sillier function The name: second_func The class:

Now I'll call the function passed in Second function was called

callable objects

Just as functions are objects that can have attributes set on them, it is possible to create an object that can be called as though it were a function.

In Python any object with a __call__() method can be called using function-call syntax.

Inheritance and Polymorphism

Inheritance and polymorphism – this is a very important concept in Python. You must understand it better if you want to learn.

Inheritance

One of the major advantages of Object Oriented Programming is re-use. Inheritance is one of the mechanisms to achieve the same. Inheritance allows programmer to create a general or a base class first and then later extend it to more specialized class. It allows programmer to write better code.

Using inheritance you can use or inherit all the data fields and methods available in your base class. Later you can add you own methods and data fields, thus inheritance provides a way to organize code, rather than rewriting it from scratch.

In object-oriented terminology when class X extend class Y, then Y is called super/parent/base class and X is called subclass/child/derived class. One point to note here is that only data fields and method which are not private are accessible by child classes. Private data fields and methods are accessible only inside the class.

syntax to create a derived class is −

class BaseClass:

Body of base class

class DerivedClass(BaseClass):

Body of derived class

Inheriting Attributes

Now look at the below example −

Output

We first created a class called Date and pass the object as an argument, here-object is built-in class provided by Python. Later we created another class called time and called the Date class as an argument. Through this call we get access to all the data and attributes of Date class into the Time class. Because of that when we try to get the get_date method from the Time class object tm we created earlier possible.

Object.Attribute Lookup Hierarchy

- The instance

- The class

- Any class from which this class inherits

Inheritance Examples

Let’s take a closure look into the inheritance example −

Let’s create couple of classes to participate in examples −

- Animal − Class simulate an animal

- Cat − Subclass of Animal

- Dog − Subclass of Animal

In Python, constructor of class used to create an object (instance), and assign the value for the attributes.

Constructor of subclasses always called to a constructor of parent class to initialize value for the attributes in the parent class, then it start assign value for its attributes.

Output

In the above example, we see the command attributes or methods we put in the parent class so that all subclasses or child classes will inherits that property from the parent class.

If a subclass try to inherits methods or data from another subclass then it will through an error as we see when Dog class try to call swatstring() methods from that cat class, it throws an error(like AttributeError in our case).

Polymorphism (“MANY SHAPES”)

Polymorphism is an important feature of class definition in Python that is utilized when you have commonly named methods across classes or subclasses. This permits functions to use entities of different types at different times. So, it provides flexibility and loose coupling so that code can be extended and easily maintained over time.

This allows functions to use objects of any of these polymorphic classes without needing to be aware of distinctions across the classes.

Polymorphism can be carried out through inheritance, with subclasses making use of base class methods or overriding them.

Let understand the concept of polymorphism with our previous inheritance example and add one common method called show_affection in both subclasses −

From the example we can see, it refers to a design in which object of dissimilar type can be treated in the same manner or more specifically two or more classes with method of the same name or common interface because same method(show_affection in below example) is called with either type of objects.

Output

So, all animals show affections (show_affection), but they do differently. The “show_affection” behaviors is thus polymorphic in the sense that it acted differently depending on the animal. So, the abstract “animal” concept does not actually “show_affection”, but specific animals(like dogs and cats) have a concrete implementation of the action “show_affection”.

Python itself have classes that are polymorphic. Example, the len() function can be used with multiple objects and all return the correct output based on the input parameter.

Overriding

In Python, when a subclass contains a method that overrides a method of the superclass, you can also call the superclass method by calling

Super(Subclass, self).method instead of self.method.

Example

class Thought(object):

def __init__(self):

pass

def message(self):

print("Thought, always come and go")

class Advice(Thought):

def __init__(self):

super(Advice, self).__init__()

def message(self):

print('Warning: Risk is always involved when you are dealing with market!')

Inheriting the Constructor

If we see from our previous inheritance example, __init__ was located in the parent class in the up ‘cause the child class dog or cat didn’t‘ve __init__ method in it. Python used the inheritance attribute lookup to find __init__ in animal class. When we created the child class, first it will look the __init__ method in the dog class, then it didn’t find it then looked into parent class Animal and found there and called that there. So as our class design became complex we may wish to initialize a instance firstly processing it through parent class constructor and then through child class constructor.

Output

In above example- all animals have a name and all dogs a particular breed. We called parent class constructor with super. So dog has its own __init__ but the first thing that happen is we call super. Super is built in function and it is designed to relate a class to its super class or its parent class.

In this case we saying that get the super class of dog and pass the dog instance to whatever method we say here the constructor __init__. So in another words we are calling parent class Animal __init__ with the dog object. You may ask why we won’t just say Animal __init__ with the dog instance, we could do this but if the name of animal class were to change, sometime in the future. What if we wanna rearrange the class hierarchy,so the dog inherited from another class. Using super in this case allows us to keep things modular and easy to change and maintain.

So in this example we are able to combine general __init__ functionality with more specific functionality. This gives us opportunity to separate common functionality from the specific functionality which can eliminate code duplication and relate class to one another in a way that reflects the system overall design.

Conclusion

__init__ is like any other method; it can be inherited

If a class does not have a __init__ constructor, Python will check its parent class to see if it can find one.

As soon as it finds one, Python calls it and stops looking

We can use the super () function to call methods in the parent class.

We may want to initialize in the parent as well as our own class.

Multiple Inheritance and the Lookup Tree

As its name indicates, multiple inheritance is Python is when a class inherits from multiple classes.

For example, a child inherits personality traits from both parents (Mother and Father).

Python Multiple Inheritance Syntax

To make a class inherits from multiple parents classes, we write the the names of these classes inside the parentheses to the derived class while defining it. We separate these names with comma.

Below is an example of that −

>>> class Mother:

pass

>>> class Father:

pass

>>> class Child(Mother, Father):

pass

>>> issubclass(Child, Mother) and issubclass(Child, Father)

True

Multiple inheritance refers to the ability of inheriting from two or more than two class. The complexity arises as child inherits from parent and parents inherits from the grandparent class. Python climbs an inheriting tree looking for attributes that is being requested to be read from an object. It will check the in the instance, within class then parent class and lastly from the grandparent class. Now the question arises in what order the classes will be searched - breath-first or depth-first. By default, Python goes with the depth-first.

That’s is why in the below diagram the Python searches the dothis() method first in class A. So the method resolution order in the below example will be

Mro- D→B→A→C

Look at the below multiple inheritance diagram −

Let’s go through an example to understand the “mro” feature of an Python.

Output

Example 3

Let’s take another example of “diamond shape” multiple inheritance.

Above diagram will be considered ambiguous. From our previous example understanding “method resolution order” .i.e. mro will be D→B→A→C→A but it’s not. On getting the second A from the C, Python will ignore the previous A. so the mro will be in this case will be D→B→C→A.

Let’s create an example based on above diagram −

Output

Simple rule to understand the above output is- if the same class appear in the method resolution order, the earlier appearances of this class will be remove from the method resolution order.

In conclusion −

Any class can inherit from multiple classes

Python normally uses a “depth-first” order when searching inheriting classes.

But when two classes inherit from the same class, Python eliminates the first appearances of that class from the mro.

Decorators, Static and Class Methods

Functions(or methods) are created by def statement.

Though methods works in exactly the same way as a function except one point where method first argument is instance object.

We can classify methods based on how they behave, like

Simple method − defined outside of a class. This function can access class attributes by feeding instance argument:

def outside_func(():

Instance method −

def func(self,)

Class method − if we need to use class attributes

@classmethod

def cfunc(cls,)

Static method − do not have any info about the class

@staticmethod

def sfoo()

Till now we have seen the instance method, now is the time to get some insight into the other two methods,

Class Method

The @classmethod decorator, is a builtin function decorator that gets passed the class it was called on or the class of the instance it was called on as first argument. The result of that evaluation shadows your function definition.

syntax

class C(object):

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

....

fun: function that needs to be converted into a class method

returns: a class method for function

They have the access to this cls argument, it can’t modify object instance state. That would require access to self.

It is bound to the class and not the object of the class.

Class methods can still modify class state that applies across all instances of the class.

Static Method

A static method takes neither a self nor a cls(class) parameter but it’s free to accept an arbitrary number of other parameters.

syntax

class C(object):

@staticmethod

def fun(arg1, arg2, ...):

...

returns: a static method for function funself.

- A static method can neither modify object state nor class state.

- They are restricted in what data they can access.

When to use what

We generally use class method to create factory methods. Factory methods return class object (similar to a constructor) for different use cases.

We generally use static methods to create utility functions.

Python Design Pattern

Overview

Modern software development needs to address complex business requirements. It also needs to take into account factors such as future extensibility and maintainability. A good design of a software system is vital to accomplish these goals. Design patterns play an important role in such systems.

To understand design pattern, let’s consider below example −

Every car’s design follows a basic design pattern, four wheels, steering wheel, the core drive system like accelerator-break-clutch, etc.

So, all things repeatedly built/ produced, shall inevitably follow a pattern in its design.. it cars, bicycle, pizza, atm machines, whatever…even your sofa bed.

Designs that have almost become standard way of coding some logic/mechanism/technique in software, hence come to be known as or studied as, Software Design Patterns.

Why is Design Pattern Important?

Benefits of using Design Patterns are −

Helps you to solve common design problems through a proven approach.

No ambiguity in the understanding as they are well documented.

Reduce the overall development time.

Helps you deal with future extensions and modifications with more ease than otherwise.

May reduce errors in the system since they are proven solutions to common problems.

Classification of Design Patterns

The GoF (Gang of Four) design patterns are classified into three categories namely creational, structural and behavioral.

Creational Patterns

Creational design patterns separate the object creation logic from the rest of the system. Instead of you creating objects, creational patterns creates them for you. The creational patterns include Abstract Factory, Builder, Factory Method, Prototype and Singleton.

Creational Patterns are not commonly used in Python because of the dynamic nature of the language. Also language itself provide us with all the flexibility we need to create in a sufficient elegant fashion, we rarely need to implement anything on top, like singleton or Factory.

Also these patterns provide a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using a new operator.

Structural Patterns

Sometimes instead of starting from scratch, you need to build larger structures by using an existing set of classes. That’s where structural class patterns use inheritance to build a new structure. Structural object patterns use composition/ aggregation to obtain a new functionality. Adapter, Bridge, Composite, Decorator, Façade, Flyweight and Proxy are Structural Patterns. They offers best ways to organize class hierarchy.

Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral patterns offers best ways of handling communication between objects. Patterns comes under this categories are: Visitor, Chain of responsibility, Command, Interpreter, Iterator, Mediator, Memento, Observer, State, Strategy and Template method are Behavioral Patterns.

Because they represent the behavior of a system, they are used generally to describe the functionality of software systems.

Commonly used Design Patterns

Singleton

It is one of the most controversial and famous of all design patterns. It is used in overly object-oriented languages, and is a vital part of traditional object-oriented programming.

The Singleton pattern is used for,

When logging needs to be implemented. The logger instance is shared by all the components of the system.

The configuration files is using this because cache of information needs to be maintained and shared by all the various components in the system.

Managing a connection to a database.

Here is the UML diagram,

class Logger(object):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if not hasattr(cls, '_logger'):

cls._logger = super(Logger, cls).__new__(cls, *args, **kwargs)

return cls._logger

In this example, Logger is a Singleton.

When __new__ is called, it normally constructs a new instance of that class. When we override it, we first check if our singleton instance has been created or not. If not, we create it using a super call. Thus, whenever we call the constructor on Logger, we always get the exact same instance.

>>>

>>> obj1 = Logger()

>>> obj2 = Logger()

>>> obj1 == obj2

True

>>>

>>> obj1

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

>>> obj2

<__main__.Logger object at 0x03224090>

Object Oriented Python - Advanced Features

In this we will look into some of the advanced features which Python provide

Core Syntax in our Class design

In this we will look onto, how Python allows us to take advantage of operators in our classes. Python is largely objects and methods call on objects and this even goes on even when its hidden by some convenient syntax.

>>> var1 = 'Hello'

>>> var2 = ' World!'

>>> var1 + var2

'Hello World!'

>>>

>>> var1.__add__(var2)

'Hello World!'

>>> num1 = 45

>>> num2 = 60

>>> num1.__add__(num2)

105

>>> var3 = ['a', 'b']

>>> var4 = ['hello', ' John']

>>> var3.__add__(var4)

['a', 'b', 'hello', ' John']

So if we have to add magic method __add__ to our own classes, could we do that too. Let’s try to do that.

We have a class called Sumlist which has a contructor __init__ which takes list as an argument called my_list.

class SumList(object):

def __init__(self, my_list):

self.mylist = my_list

def __add__(self, other):

new_list = [ x + y for x, y in zip(self.mylist, other.mylist)]

return SumList(new_list)

def __repr__(self):

return str(self.mylist)

aa = SumList([3,6, 9, 12, 15])

bb = SumList([100, 200, 300, 400, 500])

cc = aa + bb # aa.__add__(bb)

print(cc) # should gives us a list ([103, 206, 309, 412, 515])

Output

[103, 206, 309, 412, 515]

But there are many methods which are internally managed by others magic methods. Below are some of them,

'abc' in var # var.__contains__('abc')

var == 'abc' # var.__eq__('abc')

var[1] # var.__getitem__(1)

var[1:3] # var.__getslice__(1, 3)

len(var) # var.__len__()

print(var) # var.__repr__()

Inheriting From built-in types

Classes can also inherit from built-in types this means inherits from any built-in and take advantage of all the functionality found there.

In below example we are inheriting from dictionary but then we are implementing one of its method __setitem__. This (setitem) is invoked when we set key and value in the dictionary. As this is a magic method, this will be called implicitly.

class MyDict(dict):

def __setitem__(self, key, val):

print('setting a key and value!')

dict.__setitem__(self, key, val)

dd = MyDict()

dd['a'] = 10

dd['b'] = 20

for key in dd.keys():

print('{0} = {1}'.format(key, dd[key]))

Output

setting a key and value!

setting a key and value!

a = 10

b = 20

Let’s extend our previous example, below we have called two magic methods called __getitem__ and __setitem__ better invoked when we deal with list index.

# Mylist inherits from 'list' object but indexes from 1 instead for 0!

class Mylist(list): # inherits from list

def __getitem__(self, index):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

return list.__getitem__(self, index) # this method is called when

# we access a value with subscript like x[1]

def __setitem__(self, index, value):

if index == 0:

raise IndexError

if index > 0:

index = index - 1

list.__setitem__(self, index, value)

x = Mylist(['a', 'b', 'c']) # __init__() inherited from builtin list

print(x) # __repr__() inherited from builtin list

x.append('HELLO'); # append() inherited from builtin list

print(x[1]) # 'a' (Mylist.__getitem__ cutomizes list superclass

# method. index is 1, but reflects 0!

print (x[4]) # 'HELLO' (index is 4 but reflects 3!

Output

['a', 'b', 'c']

a

HELLO

In above example, we set a three item list in Mylist and implicitly __init__ method is called and when we print the element x, we get the three item list ([‘a’,’b’,’c’]). Then we append another element to this list. Later we ask for index 1 and index 4. But if you see the output, we are getting element from the (index-1) what we have asked for. As we know list indexing start from 0 but here the indexing start from 1 (that’s why we are getting the first item of the list).

Naming Conventions

In this we will look into names we’ll used for variables especially private variables and conventions used by Python programmers worldwide. Although variables are designated as private but there is not privacy in Python and this by design. Like any other well documented languages, Python has naming and style conventions that it promote although it doesn’t enforce them. There is a style guide written by “Guido van Rossum” the originator of Python, that describe the best practices and use of name and is called PEP8. Here is the link for this, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/

PEP stands for Python enhancement proposal and is a series of documentation that distributed among the Python community to discuss proposed changes. For example it is recommended all,

- Module names − all_lower_case

- Class names and exception names − CamelCase

- Global and local names − all_lower_case

- Functions and method names − all_lower_case

- Constants − ALL_UPPER_CASE

These are just the recommendation, you can vary if you like. But as most of the developers follows these recommendation so might me your code is less readable.

Why conform to convention?

We can follow the PEP recommendation we it allows us to get,

- More familiar to the vast majority of developers

- Clearer to most readers of your code.

- Will match style of other contributers who work on same code base.

- Mark of a professional software developers

- Everyone will accept you.

Variable Naming − ‘Public’ and ‘Private’

In Python, when we are dealing with modules and classes, we designate some variables or attribute as private. In Python, there is no existence of “Private” instance variable which cannot be accessed except inside an object. Private simply means they are simply not intended to be used by the users of the code instead they are intended to be used internally. In general, a convention is being followed by most Python developers i.e. a name prefixed with an underscore for example. _attrval (example below) should be treated as a non-public part of the API or any Python code, whether it is a function, a method or a data member. Below is the naming convention we follow,

Public attributes or variables (intended to be used by the importer of this module or user of this class) −regular_lower_case