科学者たちは、腸内プリンを詰め込んだゾンビ感染セミを見つけるためにあなたの助けを必要としています

この春、奇妙な宝探しゲームをしたい気分なら、ラッキーだ。昆虫学者たちは、ゾンビセミ菌としても知られる寄生虫マッソスポラ・シカディナに侵食された成虫の幼虫セミを目撃したことを一般の人々に報告するよう呼びかけている。探している人には簡単にヒントが見つかるだろう。侵食されたセミの腹部はプリンのような菌の塊でどんどん満たされ、最終的にはお尻と生殖器がきれいに落ちてしまうのだ。

関連性のあるコンテンツ

世の中には邪悪な寄生虫が数多くいるが、M. cicadina はまさにホラー映画にぴったりの寄生虫だ。この寄生虫は、他の寄生虫よりもずっと長いライフサイクルを持つMagicicada属の特定のセミに寄生する。北米に生息するいわゆる周期ゼミは 、通常 4 月下旬から 6 月上旬にかけて、一度に 13 年または 17 年ごとに土から大量に出現する。地表で生きられる残りの数週間の間に、これらのセミは交尾して次世代の卵を産み、卵が孵って地中に潜り込み、このプロセスを繰り返す。周期ゼミは、出現予定に基づいて群れに分けられるが、群れは複数の種から構成される。

関連性のあるコンテンツ

- オフ

- 英語

今年は特にユニークなセミの季節です。現在活動中の 15 の群れのうち 2 つの群れが出現したからです。1 つはイリノイ州北部に集中している 17 年目の群れ XIII で、もう 1 つは米国南東部全体に広く分布する 13 年目の群れ XIX です。これらのセミの出現は、M. cicadina が地上に姿を現すことも意味しており、ウェストバージニア大学の森林病理学および菌類学の教授であるマシュー カッソン氏のような科学者にとって刺激的な機会となります。

“Our fungus is what they call an obligate biotroph, which means that it needs a cicada host to survive. You can’t rear them in the lab, because you can’t rear 17-year cicadas in the lab,” Kasson told Gizmodo over the phone. “So we rely exclusively on harvesting fungal plugs from the backside of infected cicadas that are collected during outbreaks. And it’s critical that we collect as many as we can.”

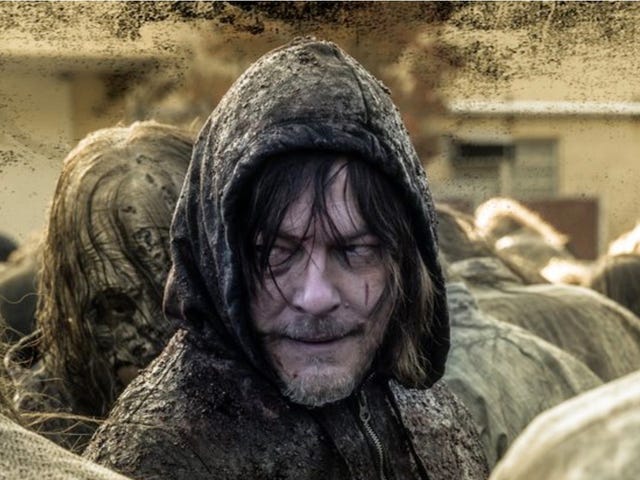

Like their hosts, M. cicadina has a complicated life cycle, filled with sex and drugs. Some cicadas become infected with the spore form of the fungi as they begin to burrow out of the soil toward adulthood. These cicadas develop a specific type of infection classified as stage I. Stage I infected cicadas will appear normal at first, but after about a week, their lower abdomen—genitals included—begins to rip apart, having been replaced by a mass of whitish fungal tissue. The fungal plugs are loaded with spores that can infect healthy cicadas.

Males are more likely than females to lose their abdomen and junk completely, but it doesn’t stop them from trying to mate, and that’s when things somehow get even weirder. Though both sexes get stage I infections that they can spread to others, infected males will try to have sex with any cicada around. In addition to making the usual mating call of males, some infected also begin to act like females, stealing their mating ritual of wing-flapping to entice healthy males into futilely courting them. These rampant orgies don’t help the cicadas any, but they do fuel the parasite’s continued spread.

Scientists still don’t know exactly how the fungus warps the cicadas’ behavior so dramatically, but several years ago Kasson and his colleagues made a key discovery. Once inside a host, M. cicadina seems to produce ample amounts of cathinone, a type of stimulant, which likely plays a big part in keeping the cicadas driven to mate while ignoring any other distractions, such as a missing butt. They also found that other Massospora species that infect annual cicadas can produce psilocybin, the main ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms.

But there’s still so much that we’re in the dark about when it comes to these devious parasites—mysteries that will require plenty of samples for researchers like Kasson to sift through.

There’s a second stage of M. cicadina infection, for instance. These stage II infections still hollow out the cicadas’ abdomen but will now produce thicker-walled resting spores (Kasson describes these fungal plugs as resembling a ‘“creamy pudding”). Stage II male cicadas also no longer turn into pansexual horndogs. The resting spores aren’t intended to infect adult cicadas, but are ticking time bombs that will seed the soil and wait to infect the next generation of nymphs unlucky enough to encounter them 13 to 17 years down the road.

Stage II infections are caught from Stage I infected adult cicadas and tend to show up later in the season. But according to Kasson, the exact details behind the transition from Stage I to Stage II infections are still unclear. It’s not known whether adult cicadas can catch Stage I infections from other infected adults if caught early enough in the season, for instance, or if a Stage I infection will always cause a stage II infection.

Another lingering question concerns the cicada broods. The team’s earlier analysis found evidence that the M. cicadina parasites infecting 13-year cicadas are slightly different on a genetic level from the M. cicadina infecting 17-year cicadas. That leaves open the possibility that these two groups of parasites are actually two different species. But since there are much fewer 13-year broods around today (only three out of 15), Kasson’s team has only had limited samples to work with to date. The next 13-year brood after this one won’t arrive until 2027, so the researchers are hoping to nab as many as these cicadas as possible before the season ends.

“We really have to be opportunists and take advantage of these emergences when we can,” Kasson noted.

In the last few weeks, Kasson has made a call out to the public through social media. The ask is simple enough: People who come across likely infected cicadas should photograph and upload their pictures though either iNaturalist or the more specific CicadaSafari. They can also get in touch with Kasson directly through his X/Twitter handle @imperfectfunguy. While Kasson’s team is most eager to collect actual specimens, no observation is too small.

One thing you shouldn’t do if you see a fungal-infected cicada is try to eat their gut pudding—a real possibility that Kasson has had to warn overly curious people against, especially those interested in the stimulants found inside.

“The cathinone we found in the cicadas was just one of 1,000 different compounds we found that were tied specifically to the fungus. And if you were to eat the plugs, you might find mycotoxins, bacteria, nematodes, or other microbes that could be really harmful to you,” he said. “So I would say probably not worth the risk.”