Im Laufe der Jahrhunderte sind viele bemerkenswerte Wissenschaftler aus spanischsprachigen Ländern, Kulturen und Vorfahren hervorgegangen. Obwohl es nicht ideal ist, eine so unterschiedliche Ansammlung von Menschen unter einer einzigen Rubrik zusammenzufassen – insbesondere der politisch sinnvolle, aber zweifelhafte Begriff Hispanoamerikaner –, schafft es doch Raum, ihre weitreichenden Hintergründe und Errungenschaften zu untersuchen.

Nehmen Sie diese beiden herausragenden Mediziner, die beide in Caracas, Venezuela, geboren wurden und die Sie gleich kennenlernen werden. Der erste, ein Kind spanischer Einwanderer, verbrachte sein Leben in seiner Heimat und widmete sich dort der Behandlung der Lepra; der zweite, Sohn spanisch-marokkanischer und französisch-marokkanischer Eltern, verbrachte seine prägenden Jahre in Paris und den größten Teil seines Lebens in Amerika und studierte die genetischen Ursachen von Autoimmunerkrankungen . Ähnlich und doch Welten voneinander entfernt; das ist diese Liste in Kürze.

- Carlos Juan Finlay (1833-1915)

- Bernardo Alberto Houssay (1887-1971)

- Alfonso Caso und Andrade (1896-1970)

- Luis Federico Leloir (1906-1987)

- Luis Alvarez (1911-1988)

- Jacinto Convit (1913–2014)

- Baruj Benacerraf (1920-2011)

- César Milstein (1927-2002)

- Mario J. Molina (1943-)

- Franklin Chang-Díaz (1950-) und Ellen Ochoa (1958-)

10: Carlos Juan Finlay (1833-1915)

Vor Google Doodles haben wir wichtige vergessene Persönlichkeiten mit Briefmarken geehrt. Carlos Juan Finlay, der kubanische Arzt, der 1881 erstmals Gelbfieber mit Moskitos in Verbindung brachte, erhielt beide Ehrungen. Angesichts der Tausenden von Leben, die er gerettet hat, und der Jahrzehnte der Verachtung, die er ertragen musste, würden wir sagen, dass er sie verdient hat.

Geboren in Puerto Príncipe, Kuba, studierte Finlay im Ausland, bevor er als praktischer Arzt und Augenarzt mit einem Hang zur wissenschaftlichen Forschung nach Havanna zurückkehrte. Zu dieser Zeit verwüstete das Gelbfieber noch die Tropen, terrorisierte die Bevölkerung und störte die Schifffahrt, insbesondere in Havanna [Quellen: Frierson ; Haas ; PBS ; WER ; UVHSL ].

Finlay bemerkte, dass Gelbfieberepidemien ungefähr mit der Moskitosaison in Havanna zusammenfielen, aber seine Moskitoübertragungshypothese stieß jahrzehntelang auf Verachtung, bis er den amerikanischen Militärchirurgen Walter Reed (wie das Krankenhaus) davon überzeugte, sich damit zu befassen. Reed und seine Kollegen, die nach Kuba entsandt worden waren, um die Krankheit zu bekämpfen, die so viele Soldaten während des Spanisch-Amerikanischen Krieges getötet hatte, halfen Finlay, seine Experimente zu verbessern und bestätigten, dass die Art, die jetzt als Aedes aegypti bekannt ist , tatsächlich der Übeltäter war. Das Gelbfieber wurde sowohl in Kuba als auch in Panama ausgerottet, was es den Ingenieuren ermöglichte, den Panamakanal endlich fertigzustellen [Quellen: Haas ; PBS ; UVHSL ].

Heute betrifft Gelbfieber etwa 200.000 und tötet jährlich 30.000 Menschen, hauptsächlich in afrikanischen Gebieten, in denen es an Impfstoffen mangelt. Symptomreduktion bleibt die einzige Behandlung; Unbehandelt hat die Krankheit eine Sterblichkeitsrate von 50 Prozent. Das Auftreten von Gelbfieber hat in den letzten Jahren stark zugenommen [Quellen: WHO ].

9: Bernardo Alberto Houssay (1887-1971)

Wir sind uns alle schmerzlich bewusst, wie Wachstum, Geschlechtsreife und Stoffwechsel während der Pubertät auf Hochtouren laufen, aber wir sind normalerweise zu abgelenkt, um die winzige bohnenförmige Drüse mit ihrem Fuß auf dem Gaspedal zu betrachten. Bernardo Alberto Houssay war selbst kaum aus der Pubertät heraus , als er anfing, die Hypophyse zu erforschen , aber dann war er immer ein kleines Wunderkind: Die Intelligenz, die ihm half, sich von seinen sieben Geschwistern abzuheben, hatte ihm zuvor einen Platz in der Pharmazieschule im Alter eingebracht 14.

Houssays Forschungen über die Beziehung zwischen dem Zuckerstoffwechsel und einem Hypophysenhormon brachten ihm 1947 den Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin ein und markierten, was noch wichtiger ist, einen Wendepunkt in der Diabetesbehandlung. Er teilte sich den Preis mit Carl Cori und Gerty Cori (geb. Radnitz), Pionieren im Verständnis der katalytischen Umwandlung von Glykogen [Quellen: Magill ; Nobelpreis ; USASEF ].

Houssay wurde in Buenos Aires, Argentinien, geboren und forschte in den Bereichen Kreislauf, Atmung, Immunität, Nervensystem, Verdauung und Behandlung von Insekten- und Schlangenbissen. Obwohl er zu den 150 Pädagogen gehörte, die während des Militärputsches von General Juan Perón 1943 entlassen wurden, wurde er zu einem der einflussreichsten Mediziner und Wissenschaftler Lateinamerikas im 20. Jahrhundert. Sein Einfluss war durch seine umfangreichen Veröffentlichungen, sein weit verbreitetes Lehrbuch „Human Physiology“ und seine Organisation des Instituts für Physiologie an der Universität von Buenos Aires zu spüren, das medizinische Koryphäen wie Luis Leloir und César Milstein hervorbrachte, die beide auf dieser Liste stehen [Quellen: Magill ; Haussay ; USASEF ].

8: Alfonso Caso und Andrade (1896-1970)

The man credited with one of the most important Mesoamerican discoveries in history started out lecturing on legal philosophy. After discovering a love of ancient regional architecture and writing systems, the Mexico City native began taking classes in anthropology. In 1925, Alfonso Caso y Andrade added an M.A. in the subject to his philosophy master's degree and law degree, all from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) [sources: Anthropology News; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Gaillard ; Smithsonian].

Caso's exploration of early Oaxacan cultures led him to the monumental discovery and excavation of Tomb Seven at Monte Albán. By studying burial offerings there, he proved that the Mixtec people succeeded the Zapotec as masters of the city. His finding further enabled him to define five major phases of the ancient capital's history, beginning in the 8th century B.C.E., that lined up with the history of other sites. These endeavors, combined with his contributions to cracking the Mixtec Codices, marked his best-known accomplishments in anthropology [sources: Anthropology News; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Gaillard ; Smithsonian].

But Caso's influence extended far beyond the sciences. He was also a teacher, attorney, administrator, archaeologist and advocate for Mexico's American Indians. He also served as rector of UNAM and director of the National Museum and of the National Institute of Anthropology and History [sources: Anthropology News; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Gaillard ; Smithsonian].

7: Luis Federico Leloir (1906-1987)

Much as fad diets might tell us to cut them out, energy-packed carbohydrates are essential to most life, thanks to two opposing chemical processes: combustion , which allows us to break down carbs and release energy needed for vital bodily processes, and synthesis, which enables us to use various sugars to build substances we need to live.

Before Argentine physician and biochemist Luis Federico Leloir did his groundbreaking research into the transformation of one sugar into another, combustion was well-understood, but synthesis remained a mysterious, largely guessed-at phenomenon. By isolating a new class of substances called sugar nucleotides, Leloir found the key to deciphering this voluminous backlog of unsolved metabolic reactions. A new field of biochemistry opened up virtually overnight, and Leloir received the 1970 Nobel Prize in chemistry [sources: Myrbäck; Parodi].

Leloir was born in Paris to Argentine parents and lived in Buenos Aires from the age of 2, with the exception of a few years spent abroad. After earning his medical degree from the University of Buenos Aires, he worked at the Institute of Physiology with Bernardo Houssay. In 1947, he established the Institute for Biochemical Research, Buenos Aires, where he began the lactose, or milk sugar, research that would lead to his great breakthrough [sources: Leloir; May].

6: Luis Alvarez (1911-1988)

A quick glance at Luis Alvarez's array of research and engineering projects reveals why colleagues described him as the "prize wild idea man." A sample: He built U.S. President Eisenhower an indoor golf-training machine, analyzed the Zapruder film and tried to locate an Egyptian pyramid's treasure chamber using cosmic rays [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; PBS; Sullivan; Wohl].

In 1938, Alvarez identified orbital-electron capture, radioactive decay in which a nucleus absorbs an orbital electron. The following year, he and Felix Bloch pioneered measuring a neutron's magnetic moment, that is, its tendency to align with an applied magnetic field (an important clue that the neutrally charged particle is made of electrically charged fundamental particles). During World War II, he invented several radar applications, worked on the Manhattan Project and rode in a chase plane during the Enola Gay's Hiroshima bombing. After the war, he worked on the first proton linear accelerator and was awarded the 1968 Nobel Prize in physics for his work with elementary particles [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; PBS; Sullivan; Wohl].

Physicists had already constructed cloud chambers and bubble chambers, which spotted speeding, charged particles via condensing vapor or boiling liquid. But tiny resonance particles, which existed for a trillionth of a trillionth of a second, were only detectable by the traces they left behind -- disintegration products and collision reactions with other particles. To tackle the task, Alvarez developed his own bubble chamber, camera stabilizers and a computerized system for analyzing bubble photographs. Together with the linear accelerators that he helped pioneer, these revolutionized the discovery of elemental particles, which he and his team discovered by the truckload [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Nobel Prize; PBS; Sullivan; Wohl].

5: Jacinto Convit (1913-2014)

The world will forever associate two names with leprosy, aka Hansen's disease: Norwegian physician Gerhard Hansen, who in 1873 discovered the bacterium that causes it; and Jacinto Convit, who created a new vaccine for the slow-acting, disfiguring and deadly disease by combining a known tuberculosis treatment with an armadillo bacterium in 1987 [sources: BBC; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Chinea; Yandell].

But Convit, who was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and died there a century later, extended his hand beyond the confines of the lab or doctor's office. Moved after encountering the disease's poor and stigmatized victims during medical school, he soon dedicated himself to helping treat them and to combating the social stigma under which they lived [sources: BBC; Chinea].

Convit also developed a vaccination against leishmaniasis, a protozoal skin disease linked to poverty and malnutrition. It is transmitted by sand fly bites [source: BBC; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Chinea].

Convit’s vaccines for leprosy and leishmaniasis are no longer in use, and the search continues for universally effective and acceptable vaccines for both diseases.

During his 75-year career, he received several honors, including Spain's Prince of Asturias Award and France's Legion of Honor. Venezuela nominated him for a Nobel Prize in 1988, but he did not win. When asked if he regretted not winning the Nobel, Convit reportedly replied that his great regret was not curing cancer [sources: BBC; Chinea; Nobel Prize].

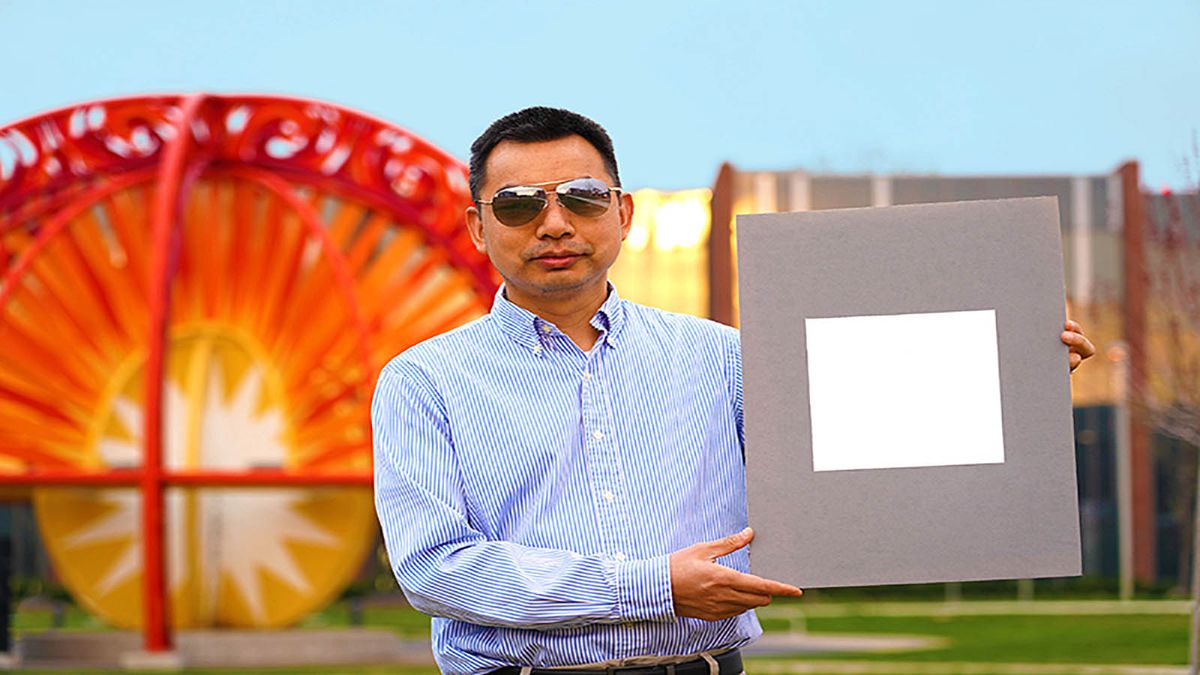

4: Baruj Benacerraf (1920-2011)

We like to view ourselves as special snowflakes, as one-of-a-kind as our fingerprints . In a way, we are: The surfaces of our cells teem with a unique array of antigens that identify us and prevent our own immune systems, under normal circumstances, from attacking those cells. Ascertaining the genetic basis of this major histocompatibility complex, or MHC, earned Baruj Benacerraf the 1980 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine and advanced our understanding of immune response and autoimmune diseases (such as multiple sclerosis) by leaps and bounds. He shared the award with George D. Snell, who uncovered the initial evidence for the MHC in the 1940s in mice, and Jean Dausset, the first to find a human compatibility antigen [sources: Benacerraf; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Nobel Prize].

Benacerraf was born in Caracas, Venezuela, but lived in Paris as a youth and spent most of his life and career in America. There he became a naturalized citizen in 1943 after serving in a U.S. Army wartime medical training program that drafted him out of medical school. His father hailed from Spanish Morocco, but he was greatly influenced by his French-Algerian mother's culture. Benacerraf later recalled how the mixture of his heritage and upbringing created difficulties for him both in America and when he later temporarily moved to Paris [sources: Benacerraf; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Nobel Prize].

3: César Milstein (1927-2002)

Speaking of the immune system, when using antibodies to combat viruses or bacteria, the human immune system favors an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach. Unfortunately, the resulting soup of B cells and immunoglobulin is unsuited to targeted research. When César Milstein produced the first monoclonal antibodies in 1975, he not only solved this problem, he became one of the fathers of modern medicine.

At the time, researchers were struggling to create targeted pure antibodies that worked against known agents. Certain mouse spleen cells offered hope, but the specific antibodies they produced died too quickly to be useful. By combining these cells with immortal myeloma cells, Milstein and postdoc Georges Köhler produced large amounts of long-lived, identical (monoclonal) antibodies. For his work, Milstein shared the 1984 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with Köhler and Niels K. Jerne [sources: Nobel Prize].

Since then, researchers have applied his technique to other antibody hybrids and produced a versatile array of assays and diagnostics, including tools used in pregnancy tests, biomarkers, cancer treatments, highly specific vaccines, and blood and tissue typing [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Chang; Telegraph UK].

Milstein was born to poor immigrant parents in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, and attended the universities of Buenos Aires and Cambridge, where he earned his Ph.D. In 1961, he headed a new molecular biology department in the National Microbiological Institute, but resigned a year later in reaction to Perón's persecution of intellectuals. He spent the rest of his career at Cambridge and held dual Argentine-British citizenship [sources: Chang; Nobel Prize; Telegraph UK].

2: Mario J. Molina (1943-)

The late 20th century was marked by the recognition that humans could significantly affect the environment, even Earth itself. But, beyond localized ecological concerns over DDT and the vaguer terror of nuclear winter, by the early 1970s we hadn't much considered the potentially global consequences of industry and chemistry. This was especially true in the case of the chemically inert chains of chlorine and fluorine atoms strapped to a carbon backbone known as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs.

In 1974, scientists F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario José Molina argued CFCs were not as harmless as they seemed. Instead of washing out of the sky through rainfall or oxidation, they floated into the upper stratosphere, where solar ultraviolet radiation broke them apart and set off an ozone -destroying chemical reaction. In 1985, the British Antarctica survey detected a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica, and the rest is history [sources: Nobel Prize; Nobel Prize].

As a child in Mexico City, Molina admired his aunt, a chemist, and emulated her by converting a spare bathroom into a makeshift chemistry lab. He studied in Mexico and abroad, and made his groundbreaking discovery concerning CFCs during his postdoctoral stint with Rowland at University of California, Irvine. The work earned him the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry, an honor he shared with Rowland and Paul J. Crutzen, a pioneer in studying nitrogen oxide effects on ozone destruction. Today, Molina studies strategic approaches to energy and the environment [sources: Crutzen; Nobel Prize; Nobel Prize].

1: Franklin Chang-Díaz (1950-) and Ellen Ochoa (1958-)

Our final entry jointly honors two pioneers of space: physicist Franklin Chang-Díaz, the first Hispanic-American astronaut, and engineer Ellen Ochoa, the first female Hispanic-American astronaut (see her picture on the first page).

Chang-Díaz was born in San José, Costa Rica, and earned his doctorate in Applied Plasma Physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He became an American citizen in 1977. Much of his early work concerned controlled fusion and fusion reactor design. Later, he led fusion propulsion teams at MIT and Johnson Space Center (JSC) on projects with potential Mars mission applications. He became an astronaut in 1981, served as in-orbit capsule communicator (CAPCOM) during the first Spacelab flight, and flew seven space shuttle missions. After all that excitement, he retired from NASA in 2005 [sources: NASA].

Ellen Ochoa was born in Los Angeles, Calif., and earned her master's degree and doctorate in electrical engineering from Stanford University. Ochoa researched information processing at Sandia National Laboratories and NASA Ames Research Center and listed as co-inventor on three patents in optics, object recognition and image processing. She became an astronaut in 1991 and flew four shuttle missions. In 2012, she was named JSC director -- the first Hispanic person and second woman to do so [sources: NASA; NASA].

Note: The first person of Latin American origin in space was Cuba's Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez in 1980, as part of a team from the Soviet Union. Méndez was also the first person of African heritage in space.

Lots More Information

Author's Note: 10 Hispanic Scientists You Should Know

The thing that struck me most while compiling this list was the devastating effect that political forces can have on science. Sure, politicized scientific issues like global climate change might instigate rancorous debate, but this smoke, though toxic in its own way, is nothing compared to the fire under which teachers, intellectuals and scientists have lived during many authoritarian regimes. For as long as there have been empires, juntas and dictators, there have been ideas that are easier to suppress, mock or beat down than to face in open debate.

Related Articles

- Missed in History: Luis Alvarez Part I (podcast)

- Missed in History: Luis Alvarez Part II (podcast)

- 12 Deadly Diseases Cured in the 20th Century

- 10 Oldest Known Diseases

- How Atom Smashers Work

- How the Manhattan Project Worked

- How Your Immune System Works

- What does the pituitary gland do?

Sources

- Anthropology News. "Death Notices (Alfonso Caso Andrade, Merle H. Deardoff)." Vol. 12, no. 4. Page 3. April 1971. (July 4, 2014) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/an.1971.12.4.3.4/pdf

- BBC. "Leprosy Vaccine Scientist Dies, Aged 100." May 13, 2014. (July 3, 2014) http://www.bbc.com/news/health-27389259

- Benacerraf, Baruj. "Baruj Benacerraf -- Biographical." May 2005. (July 4, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1980/benacerraf-bio.html

- Chang, Kenneth. "César Milstein, 74, Who Won Joint Nobel Prize in Medicine." The New York Times. March 26, 2002. (July 7, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/26/world/cesar-milstein-74-who-won-joint-nobel-prize-in-medicine.html

- Chinea, Eyanir. "Renowned Venezuelan Expert on Leprosy Jacinto Convit Dies." Reuters. May 12, 2014. (July 3, 2014) http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/05/12/us-venezuela-people-convit-idUSKBN0DS1A720140512

- Crutzen, Paul. "Nobel Lecture: My Life with O3, NOX and other YZOXs." Dec. 8, 1995. (July 3, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1995/crutzen-lecture.pdf

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "Alfonso Caso y Andrade." (July 4, 2014) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/98025/Alfonso-Caso-y-Andrade

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "Baruj Benacerraf." (July 4, 2014) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/60347/Baruj-Benacerraf

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "César Milstein." (July 7, 2014) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/383094/Cesar-Milstein

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Jacinto Convit." (July 3, 2014) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1984458/Jacinto-Convit

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Luis W. Alvarez." (July 4, 2014) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/18131/Luis-W-Alvarez

- Frierson, J. Gordon. "The Yellow Fever Vaccine: A History." Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. Vol. 83, no. 2. Page 77. June 2010. (July 9, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2892770/

- Gaillard, Gerald. "Alfonso Caso y Andrade (1896 - 1970)." The Routledge Dictionary of Anthropologists. Routledge. 2004.

- Haas, L. F. "Carlos Juan Finlay y Barres (1833-1915)." Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. Vol. 65, no. 2. Page. 268. 1998. (July 7, 2014) http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/65/2/268.full

- Houssay, Bernardo. "Nobel Prize. Bernardo Houssay -- Biographical." 1947. (July 4, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1947/houssay-bio.html

- Leloir, Luis. "Luis Leloir -- Biographical." 1970. (July 7, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1970/leloir-bio.html

- Magill, Frank. "Bernardo Alberto Houssay." Dictionary of World Biography. Vol. 8. Routledge. 2014.

- May, Leopold. "Luis Federico Leloir." 2006. (July 7, 2014) http://faculty.cua.edu/may/Leloir.pdf

- Meier, Natalie. "Frank Asaro, Berkeley Lab Nuclear Chemist, Dies at 86." The Daily Californian. June 18, 2014. (July 4, 2014) http://www.dailycal.org/2014/06/17/frank-asaro-uc-berkeley-nuclear-chemist-dies-age-86/

- Milstein, César. "César Milstein -- Biographical." (July 7, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1984/milstein-bio.html

- Molina, Mario J. "Mario J. Molina -- Biographical." November 2007. (July 3, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1995/molina-bio.html

- Molina, Mario J. "Nobel Lecture: Polar Ozone Depletion." Dec. 8, 1995. (July 3, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1995/molina-lecture.pdf

- Myrbäck, Karl. "Award Ceremony Speech: Luis Leloir." 1970. (July 7, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1970/press.html

- NASA. "Ellen Ochoa (Ph. D)." March 2014. (July 7, 2014) http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/ochoa.html

- NASA. "Franklin R. Chang-Díaz (Ph.D.)" September 2012. (July 7, 2014) http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/chang.html

- NASA. "Johnson Space Center Director Dr. Ellen Ochoa." Jan. 1, 2013. (July 7, 2014) http://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/about/people/orgs/bios/ochoa.html#.U7sDpfldV8E

- Nobel Prize. "Award Ceremony Speech: Luis Alvarez." 1968. (July 4, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1968/press.html

- Nobel Prize. "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1984." (July 7, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1984/

- Nobel Prize. "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1988." (July 3, 2014) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1988/

- Nobel Prize. "Seeking Signs of Compatibility." Sep. 6, 2010. (July 4, 2010) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1980/speedread.html

- Parodi, Armando. "J. Luis Federico Leloir, or How to Do Good Science in a Hostile Environment." IUBMB Life. Vol. 64, no. 6. May 9, 2012. (July 7, 2014) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/iub.1031/pdf

- PBS. "Carlos Finlay (1833-1915)." The Great Fever. Sep. 29, 2006. (July 7, 2014) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/fever/peopleevents/p_finlay.html

- PBS. "Luis Alvarez: 1911-1988." (July 4, 2014) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/boalva.html

- Smithsonian Institution. "Alfonso Caso y Andrade: 1896 – 1970." (July 4, 2014) http://anthropology.si.edu/olmec/english/archaeologists/caso.htm

- Sullivan, Walter. "Luis W. Alvarez, Nobel Physicist Who Explored Atom, Dies at 77." The New York Times. Sep. 2, 1988. (July 4, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/02/obituaries/luis-w-alvarez-nobel-physicist-who-explored-atom-dies-at-77.html

- The Telegraph (UK). "Cesar Milstein." March 26, 2002. (July 7, 2014) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1388825/Cesar-Milstein.html

- USA Science & Engineering Festival. "Role Models in Science & Engineering Achievement: Bernardo Alberto Houssay." 2012. (July 4, 2014) http://www.usasciencefestival.org/schoolprograms/2014-role-models-in-science-engineering/1162-bernardo-alberto.html#sthash.RgOj4IzR.dpuf

- University of Virginia Health Sciences Library. "Carlos Juan Finlay (1833 - 1915)." Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Aug. 08 2001. (July 7, 2014) http://yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu/reed/finlay.html

- Wohl, Charles G. "Scientist as Detective: Luis Alvarez and the Pyramid Burial Chambers, the JFK Assassination, and the End of the Dinosaurs." Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. (July 7, 2014) http://www.6911norfolk.com/d0lbln/105f06/105f06-wohl-alvarez.pdf

- World Health Organization. "Leprosy Statistics - Latest Data." (July 3, 2014) http://www.who.int/lep/situation/latestdata/en/

- World Health Organization. "Yellow Fever." March 2014. (July 7, 2014) http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs100/en/

- Yandell, Kate. "Der Lepra-Bazillus, um 1873." Der Wissenschaftler. 1. Okt. 2013. (3. Juli 2014) http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/37619/title/The-Leprosy-Bacillus--circa-1873/