"Assume a completely frictionless surface." How many times did we see that statement in our high-school physics class? And how many times did we wonder why our teachers were so eager to have us live in a fantasy world? Now, thanks to a group of scientists known as tribologists, the prospect of eliminating friction between two interacting surfaces is fast becoming a reality.

Está sendo feito de maneiras interessantes também. Por exemplo, uma equipe de pesquisadores da Universidade de Harvard estudou as folhas da planta carnívora, que apresentam sulcos microscópicos que prendem uma camada de néctar líquido entre elas. A superfície é tão escorregadia que os insetos que pousam nas folhas escorregam e caem em bolsas profundas em forma de jarro, onde as enzimas os devoram. De volta ao laboratório, os pesquisadores duplicaram a ladeira escorregadia da planta de jarro, criando uma rede aleatória de nanoposts repelentes de água e nanofibras revestidas de teflon e depois mergulhando-os em um líquido rico em flúor. O líquido formou uma camada entre as nanoestruturas, impedindo que a água e outros materiais fluíssem entre elas e criando uma superfície quase antiaderente.

What can frictionless surfaces do for you? Well, we've all flipped a few eggs on nonstick skillets , but that's just the tip of a super-slick iceberg .

- Bacterial-resistant Surfaces

- Nonstick Condiment Bottles

- Nonstick Submarines

- Deicing System for Airplanes

- Graffiti-repelling Walls

- Self-cleaning Cars

- Clog-free Pipes

- Anti-barnacle Boat Hulls

- Nonstick Gum

- Sharkskin Swimsuits

10: Bacterial-resistant Surfaces

Biofilms -- tapestries of microbes such as bacteria or fungi growing attached to a solid substrate -- cause loads of problems for health care providers. According to the National Institutes of Health, biofilm formation accounts for 65 percent of all human microbial infections [source: Ames]. You might think that fastidious cleaning is the answer to the problem, but biofilms stubbornly resist scrubbing. They also tend to shrug off the effects of antibiotics . The better solution involves preventing bacteria from attaching to a substrate in the first place. Hello, frictionless surface!

A biofilm begins its life when a few carefree microorganisms cruise by a countertop or surgical instrument and stick, either by way of gluey adhesion molecules or structures known as pili. Once attached, this small group of cells secretes an extracellular polymeric substance, or EPS, which acts like cement to hold the cells -- and their progeny -- permanently in place. But if you can interrupt the attachment process, you can stop the biofilm from forming.

That's exactly what a team of scientists from the University of Nottingham in the U.K. have done. By coating laboratory surfaces and medical devices such as catheters with an acrylate polymer similar to those used in the plastics industry, the researchers were able to prevent bacteria trailblazers from getting a toehold. The result: They found a 97 percent reduction in coverage of the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium [source: Ames].

9: Nonstick Condiment Bottles

In the 1970s, Heinz built an entire advertising campaign around its super-thick, friction friendly ketchup. The campaign borrowed Carly Simon's hit "Anticipation" and extolled the virtues of a "taste that's worth the wait."

Apparently, the food-service industry doesn't think the waste is worth the wait. Ketchup, mustard, mayonnaise and barbecue sauce that can't be coaxed from bottles mean lost revenue to restaurant owners and families trying to stretch their grocery budgets. About 1 million pounds (453,592 kilograms) of stuck-on sauces and dressings get thrown out each year worldwide, according to the Varanasi Research Group, a team of mechanical engineers and nanotechnologists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Then there's the issue of the big cap required to get condiments out of squeeze bottles. Eliminating the need for such a big cap would reduce how much plastic goes into a single bottle, which could keep 25,000 tons of petroleum-based products out of the waste stream each year [source: LiquiGlide].

The same condiment-crazy MIT team has a solution: coat the inside of bottles with a unique material that prevents ketchup, mayonnaise or any other type of sauce from sticking to the surface. Most similar coatings contain nanolubricants you might not want to ingest, but the Cambridge folks developed a food-safe material that they say is completely tasteless and nontoxic. They call it LiquiGlide and describe it as a "structured liquid" -- rigid like a solid, but slippery like a liquid. Smear the inside of a condiment bottle with LiquiGlide, and the contents slide out like, well, poop from a goose.

8: Nonstick Submarines

Engineers have obsessed over submarine design for more than 200 years, but they've been unable to eliminate one of its most vexing problems -- friction drag, a force that opposes forward motion as water sticks to the surface of the outer hull. According to some estimates, this "skin friction" accounts for roughly 65 percent of the drag on submarines [source: Pike].

One solution? A polymer ejection system. In such a system, polymer is stored in a tank and then ejected through a series of ports as the submarine moves. The polymer flows over the surface and reduces the interaction of water molecules with the surface. Unfortunately, the system also increases the weight of the vessel.

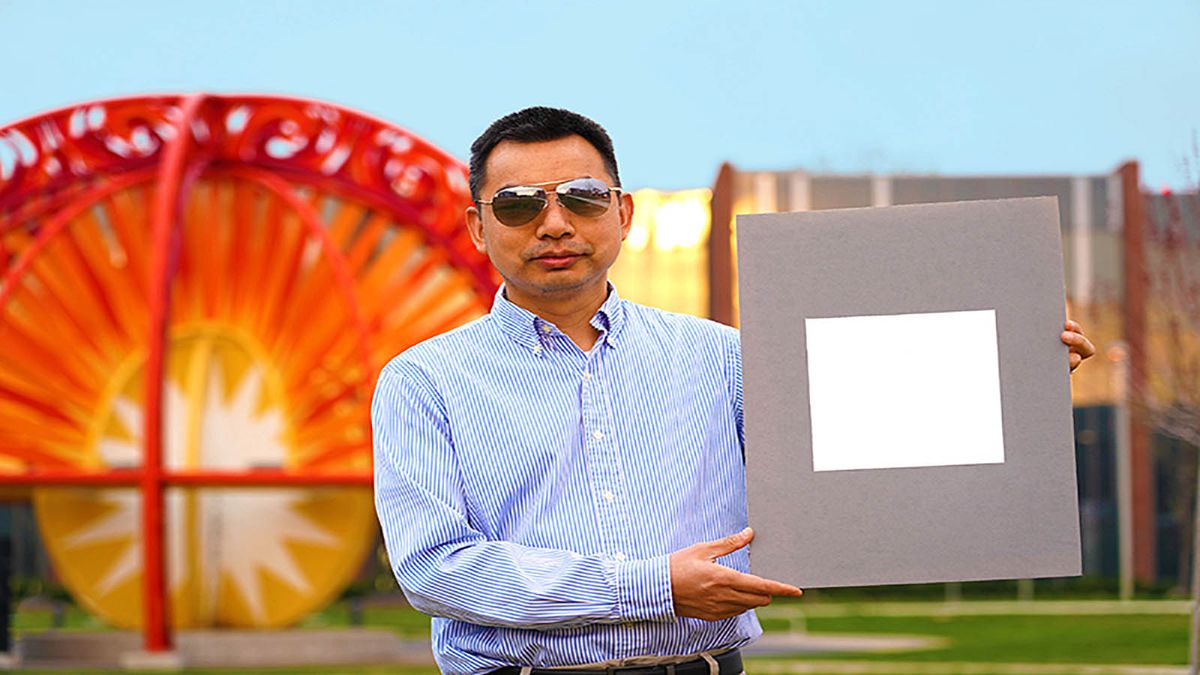

Now scientists may have a better trick: coat submarines with a nonstick surface made from a revolutionary nanotechnology. The material doesn't look extraordinarily special to the naked eye. But if you view it under a microscope, you see that it contains tiny needles spaced just a couple millionths of a meter apart. The needles rest, like a layer of grass, on a surface of Teflon. When water hits the material, it encounters air trapped in the spaces between the needles. And this makes the material extremely slippery -- 99 percent less sticky than a normal Teflon surface without the nano-sized needles [source: BBC News].

Submarines coated in the nanotechnology would have far less friction drag and would require less fuel to propel them. And, yep, a raincoat made from the same material would protect you far better than the most expensive London Fog trench coat.

7: Deicing System for Airplanes

Airplane wings provide a significant amount of lift -- as long as they maintain their factory shape. Coat a wing with even a thin layer of snow or ice, however, and you disrupt its ability to keep a plane in the air. In fact, by some estimates, ice buildup can reduce lift by as much as 25 percent, which is why ground and flight crews worry so much about deicing during wintertime air travel [source: Kaydee].

The tried-and-true method to remove ice involves a three-step strategy. During the first step, deicing, airport ground crews spray a hot solution of glycol and water on an airplane's wings. This melts existing ice but does little to prevent new ice from forming. Accomplishing this requires an anti-icing step and a second type of fluid, which contains more glycol and an additional additive to make it cling to the wing surface during takeoff. Once an aircraft reaches its cruising altitude, liquids become less effective in the fight against frozen precipitation. Jet pilots solve the problem by diverting some heat from the engines to piping in the wings. Pilots of propeller-driven planes rely on rubber boots that inflate and deflate to knock ice from the wings and tail.

But what if you could build a plane with a surface so smooth that ice fails to form in the first place? Several types of nanotechnology may soon make this a reality. Scientists from GE Global Research have developed a nanotextured, superhydrophobic (or water-repellent) coating that dramatically reduces ice adhesion on wing surfaces. And a team at North Carolina State University is experimenting with a nonstick polymer that works together with an elastic substrate. The polymer gets applied to the substrate when the elastic material is stretched slightly. When the tension is relieved, the substrate pulls the polymer molecules together into a superdense configuration. Airplane wings coated with the friction-free polymers resist being coated by anything -- even ice.

6: Graffiti-repelling Walls

It's unlikely that graffiti artists will appear on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, but cities and municipalities take this particular kind of vandalism very seriously. Chicago spent $4.1 million in 2012 on its anti-graffiti program and, in 2011, removed 137,459 instances of spray-painted artwork from bridges, buildings and signs [source: Novak]. In Los Angeles, the problem -- and the necessary budget to address it -- is even bigger. That's a lot of money and man power that could be directed to other social services and city programs.

Graffiti-cleaning crews use a variety of techniques to sponge away illicit artwork -- overpainting, chemical removal and power washing. Unfortunately, some of these methods can produce a bigger eyesore than the vandalism itself. Enter the graffiti-repelling wall, which features a nonstick material that either resists paint adhesion or makes removal far easier because the paint doesn't interact with the protected surface. Scientists have fashioned one such material to mimic the leaves of the lotus flower. The surface of these leaves bear an intricate array of microscopic ridges coated in wax. The ridges trap air between them and, as a result, water falling onto the leaf forms individual droplets that simply roll off. A wall or sign coated in such a material -- a nanostructure built in the lab but inspired by nature -- would foil graffiti artists and probably make city mayors very, very happy.

5: Self-cleaning Cars

Some people love washing their cars, but many folks would appreciate having the fresh-from-the-showroom look without all of the effort. And don't forget the environmental impact of car washing , which drains water reserves and spills pollutants into endangered wetlands. If only our cars would clean themselves.

Thanks to some researchers at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, we may be closer to a perpetually polished Prius . The scientists didn't invent a brand-new nanotechnology. Instead, they took an existing water-resistant product, already in use on some vehicles, and made it better. The original coating worked because it came embedded with nanocapsules in its surface. Those tiny capsules both repelled water and contained cleaning agents or paint droplets so that when they were ruptured, say by a key scratch, they released their contents and "healed" the blemish. Unfortunately, the capsules had a limited shelf life. To extend the self-cleaning/healing properties of the coating, the Dutch scientists have redesigned its nanostructure so that the capsules reside on stalks. When one capsule/stalk combination gets disturbed, another underlying stalk rises up and orients itself at the surface to restore the factory finish.

Cars armed with this new coating will require little more than a good rain to wash away dirt and grime. And bird droppings splashed across your door or hood may be a thing of the past.

4: Clog-free Pipes

Retailers aren't the only people who look forward to the day after Thanksgiving . Apparently, plumbers also love Black Friday , which, according to at least one source, is prime time for clogged pipes in the bathroom and kitchen [source: Henkenius]. While that peculiar relationship seems a bit mysterious (although we're sure Uncle Fred has something to do with it), the hows and whys of clogs have been known for years. They begin when a small amount of debris clings to the inside of a pipe and then acts as a nucleus upon which other material collects. For example, if you empty grease into the kitchen sink, grease sticks to the sides of the pipe and food particles stick to the grease. As the obstruction grows over time, water backs up behind the blockage.

In the house of the future, all pipes will be lined with a frictionless coating. This will prevent debris from sticking and should make clogs practically nonexistent. Many commercial enterprises have already invested in similar technology. Chemical manufacturers, for example, commonly use tubing lined with polytetrafluoroethylene, or PTFE. You may recognize PTFE by its more common brand name -- Teflon, the same material coating your nonstick pots and pans. When used in pipes and tubing, PTFE prevents fouling and clogs. It also minimizes fluid resistance, which makes manufacturing environments much more efficient.

Until you can get Teflon-lined pipes in your house, it may be best to send Uncle Fred packing. Or stock up on plungers and chemical drain cleaners.

3: Anti-barnacle Boat Hulls

Unless you own a seafaring vessel, you probably don't lose much sleep over barnacles. But for navies, marinas and commercial fishing boats , it's a serious concern. A 2011 study conducted by researchers at the United States Naval Academy found that biofouling -- that's the fancy term used to describe what happens when the small saltwater crustaceans adhere to a hull or propeller and decrease the vessel's efficiency -- costs the Navy $56 million per year or $1 billion over 15 years [source: Schultz]. And that's just for one class of ships -- the Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers .

Most of those costs involve a cleaning and painting process that's been around for centuries. First, the ship is placed in dry dock, then workers scrape the barnacles from the hull and propeller blades. Finally, they treat exposed surfaces with paint containing tin or copper. The metals in the paint are toxic to barnacle larvae, preventing them from settling down and finding a permanent home. But the paint wears off over time, which means ships must be cleaned repeatedly over their lifetimes.

Luckily, scientists have found what may be a better approach. After learning that barnacles prefer smooth surfaces, they created a micro-textured material containing tiny peaks and valleys ranging in size from 1 to 100 micrometers. Then they exposed the material to barnacle-filled seawater to measure how much attachment took place. They found that when the topography of the surface texture remained in the 30 to 45 micrometer range, barnacle settlement and attachment was reduced by 92 percent compared to smooth surfaces [source: Berntsson]. The research may lead to the first nonstick, barnacle-busting ship of the future.

2: Nonstick Gum

If you're a gum lover, especially one who lives in the concrete jungle of any major city, chew on this: Every time you spit a piece of the gooey stuff onto the ground, you end up paying for it in the form of higher taxes. That's right, scraping discarded gum from sidewalks and streets requires chemicals, steam cleaners, power washers and operators to do the dirty work. In Charleston, S.C., the city spends $200 a month just to keep three utility poles in its City Market district free of wayward wads. And in Ocean City, Md., two city employees spend three weeks every fall cleaning the sidewalks in a 14-block area near the boardwalk [source: Bryant]. It's not a new problem, either. In 1939, as part of Mayor La Guardia's campaign against gum, more than 20,000 wads of sticky stuff were removed from one spot in Times Square [source: Stead].

One U.K.-based polymer company -- Revolymer -- is working to make this particular problem a thing of the past. Its scientists have created a revolutionary gum, Rev7, that can be easily removed from a range of surfaces, including paved sidewalks, carpets, textiles and clothing. To give Rev7 its nonstick properties, the company adds a chemical to the gum base that is both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-hating or oil-loving). The polymer's affinity for oil makes the gum soft and pliable, but its attraction to water means the gum always has a film of water around it, even when it's not in someone's mouth. It's this film of water that allows someone to peel Rev7 away from any surface.

Não que isso lhe dê uma desculpa para cuspir seu chiclete onde e quando quiser. Miss Manners sugere que todos os chicletes, mesmo os sem fricção, devem ser descartados adequadamente.

1: Fatos de banho de pele de tubarão

Quer nadar como um tubarão? Então você tem que ter a pele de um tubarão . Isso parece impossível, mas se você usar uma roupa de alta tecnologia, como o LZR Racer da Speedo, estará um passo mais perto. O traje usa painéis de poliuretano para prender o ar e comprimir o corpo para aumentar a flutuabilidade e reduzir o arrasto. Mas isso é apenas o começo. O tecido do LZR Racer é revestido com nanopartículas hidrofóbicas que realmente repelem a água e diminuem o atrito ao longo do corpo do nadador. Depois que essas roupas foram introduzidas pouco antes das Olimpíadas de 2000 em Sydney, Austrália, nadadores competitivos quebraram muitos recordes mundiais , levando à sua eventual proibição nas Olimpíadas de Londres 2012 [fonte: Dorey ].

Eventualmente, trajes ainda melhores podem ser possíveis - e eles podem parecer cada vez mais com escamas de tubarão reais, que são nervuradas com ranhuras longitudinais. Essa superfície áspera reduz a formação de redemoinhos ao longo do corpo de um tubarão nadador, permitindo que deslizem pela água como um míssil quase sem atrito. A Speedo continua a experimentar texturas inspiradas em tubarões para aprimorar o design de seus trajes de banho, mesmo que os atletas olímpicos nunca consigam usá-los nas competições. Isso não deve impedi-lo, no entanto, de escorregar para uma segunda pele e acabar com a concorrência na piscina local.

Muito Mais Informações

Nota do autor: 10 usos loucos para superfícies completamente 'sem atrito'

Lembre-se de Clark W. Griswold de "Férias de Natal" do National Lampoon: "Este é o novo lubrificante de cozinha não calórico à base de silício em que minha empresa está trabalhando. Ele cria uma superfície 500 vezes mais escorregadia do que qualquer óleo de cozinha". Clark esfrega o lubrificante em seu trenó e começa a descer uma colina nevada como um idiota do inferno. Estávamos procurando soluções semelhantes, embora um pouco menos malucas, para completar este artigo.

Artigos relacionados

- 10 casos de charlatanismo médico ao longo da história

- 10 piores maneiras de morrer

- 10 pessoas realmente inteligentes que fizeram coisas realmente idiotas

- 10 maneiras completamente erradas de usar um preservativo

Origens

- Amém, Heide. "Biofilmes: Tirando o lodo perigoso do seu hospital." Notícias de compras de saúde. Julho de 2010. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.hpnonline.com/ce/pdfs/1007cetest.pdf

- Barak, Sylvie. "Trajes de banho de alta tecnologia proibidos nas Olimpíadas de Londres." EE Tempos. 3 de julho de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.eetimes.com/electronics-blogs/other/4376640/Hi-tech-swimsuits-banned-at-London-Olympics-

- BBC Notícias. "A ciência planeja um submarino 'antiaderente'." 10 de outubro de 2003. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/3178136.stm

- Berntsson KM, Johnsson PM, Lejhall M e Gatenholm P. "Análise da rejeição comportamental de superfícies micro-texturizadas e implicações para o recrutamento pela craca Balanus improvisa." Jornal de Biologia Marinha Experimental e Ecologia. 23 de agosto de 2000. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10958901

- "Tubarões biomiméticos." Instituto de Biomimética. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://biomimicryinstitute.org/home-page-content/home-page-content/biomimicking-sharks.html

- "Quebrando o Gelo: Cientistas da GE Global Research alcançam um novo avanço anti-gelo com nanotecnologia." Relatórios GE. 6 de março de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.gereports.com/breaking-the-ice/

- Bryant, Dawn. "Myrtle Beach lida com um problema pegajoso e emocionante." Myrtle Beach Online. 31 de janeiro de 2011. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.myrtlebeachonline.com/2011/01/31/1953263/gum-sticks-it-to-city.html

- Dorey, Ema. "A nanotecnologia oferece aos atletas mais do que uma chance esportiva?" O guardião. 8 de maio de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.guardian.co.uk/nanotechnology-world/does-nanotechnology-offer-athletes-more-than-a-sporting-chance

- Evans, Jon. "A planta de jarro inspira a melhor superfície antiaderente." Sociedade Real de Química. 22 de setembro de 2011. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/News/2011/September/22091101.asp

- Fahl, Daniel E. "Descongelamento de avião: como e por quê." CNN Viagens. 22 de dezembro de 2010. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://articles.cnn.com/2010-12-22/travel/airplane.deicing_1_deicing-fluid-anti-icing-ice-formation?_s=PM:TRAVEL

- "Perguntas frequentes." Site oficial da LiquiGlide. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.liqui-glide.com/

- Henkenius, Merle. "Como limpar qualquer dreno entupido." Esta Casa Velha. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.thisoldhouse.com/toh/photos/0,,20360498,00.html

- Johnson, R. Colin. "O verdadeiro polímero antiaderente elimina o atrito mecânico." EE Tempos. 8 de janeiro de 2011. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://eetimes.com/electronics-news/4166269/True-nonstick-polymer-eliminates-mechanical-friction

- Kaydee. "O acidente do vôo 3407: melhor degelo necessário?" Blog de Ética em Engenharia. 16 de fevereiro de 2009. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://engineeringethicsblog.blogspot.com/2009/02/crash-of-flight-3407-better-deicing.html

- Morelle, Rebeca e Liz Seward. "Criado chiclete 'praticamente antiaderente'." BBC Notícias. 13 de setembro de 2007. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6993719.stm

- Newcomb, Doug. "Pesquisadores desenvolvendo revestimento autolimpante para carros." Com fio. 24 de julho de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.wired.com/autopia/2012/07/self-cleaning-paint/

- "Novos materiais podem ajudar a prevenir infecções bloqueando a ligação bacteriana inicial." Notícias. 26 de outubro de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.newswise.com/articles/new-materials-may-help-prevent-infections-by-blocking-initial-bacterial-attachment

- Novak, Tim. "Remoção de graffiti mais lenta em Chicago após cortes no orçamento." Chicago Sun Times. 23 de agosto de 2012. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.suntimes.com/news/crime/14611275-418/graffiti-removal-slower-in-chicago-after-budget-cuts.html

- Pique, João. "Redução de arrasto de polímero." GlobalSecurity.org. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/ssn-drag-reduction-polymer.htm

- "Remoção Rápida." GraffitiDói. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.graffitihurts.org/rapidremoval/removal.jsp

- "Removibilidade de Rev7 Gum." Rev7 Gum Site. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.rev7gum.com/removability.php

- Schultz MP, Bendick JA, Holm ER e Hertel WM. "Impacto econômico da bioincrustação em um navio de superfície naval." Bioincrustação. 27 de janeiro de 2011. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21161774

- Calma, Débora. "Fora, Ponto Maldito." O jornal New York Times. 26 de janeiro de 2003. (16 de dezembro de 2012) http://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/26/nyregion/out-damned-spot.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm