Sự trỗi dậy và sụp đổ của câu nói cửa miệng của người Mỹ: 'Tự do, Da trắng và 21'

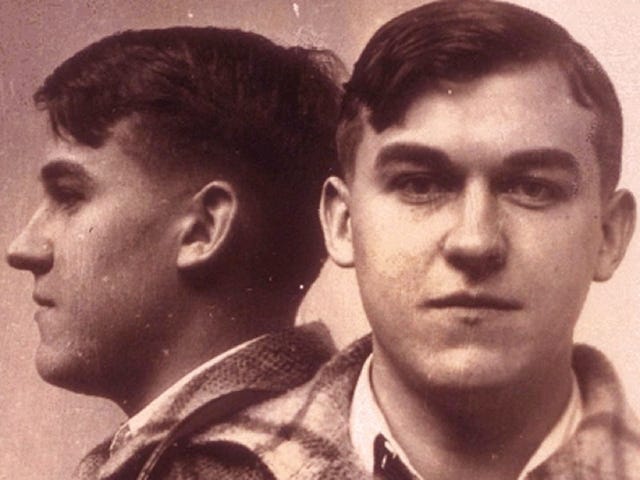

Cô ấy là một phụ nữ trẻ trong xã hội. Anh ta là một người lạ bí ẩn. Họ vừa gặp nhau trong một buổi vui chơi và khi hoàng hôn buông xuống, họ đã đỗ xe ven hồ trên chiếc xe đường trường của anh ấy để làm quen tốt hơn.

“Bạn không phiền nếu chúng ta ở lại đây một lúc,” anh hỏi, “hay bạn phải về nhà?”

Cô lùi lại, tròn mắt, xúc phạm.

“Không có điều gì bắt buộc trong cuộc sống của tôi,” cô nói, “Tôi tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi.”

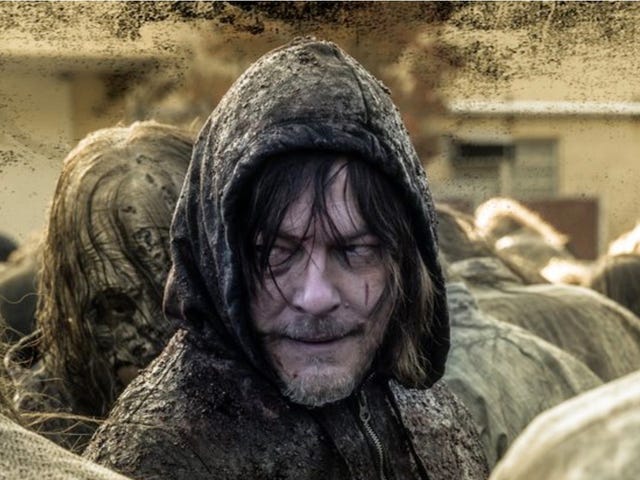

Lựa chọn từ ngữ kém cỏi, nhưng chỉ vì anh chàng là kẻ chạy trốn khỏi một băng đảng dây chuyền. Nó nằm ngay trong tiêu đề của phim: I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932). Nếu không, cả anh ấy và khán giả giả định sẽ không nghĩ nhiều hơn về biểu hiện này. Đó là một câu cửa miệng của thập kỷ, phổ biến ở khắp mọi nơi như bất kỳ meme hiện đại nào: một cách để người Mỹ da trắng kiểm tra đặc quyền của chính mình và cảm thấy phấn khích hơn là tìm ra lỗi.

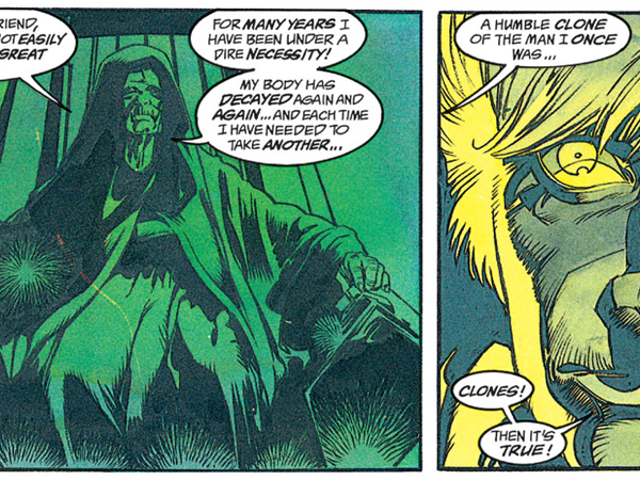

“Tự do, da trắng và 21” đã xuất hiện trong hàng chục bộ phim vào những năm 30 và 40, một khẳng định đáng tự hào đã định vị đặc quyền của người da trắng như một biện pháp ngăn chặn tranh luận cuối cùng. Tình trạng tranh cãi hiện tại về sự tồn tại và hình dạng của đặc quyền da trắng dệt lại câu chuyện về câu cửa miệng này: sự trỗi dậy, thời kỳ hoàng kim của nó và cách nó biến mất. Người Mỹ da trắng đã học được bài học tương tự như người phụ nữ trong xã hội nói “tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi” với kẻ chạy trốn: bạn không thể chắc chắn mình đang nói với ai. Mỗi khi một nhân vật trong phim thốt ra cụm từ này một cách tình cờ, họ đang cho nước Mỹ da đen một cái nhìn thoáng qua về tính cách thực sự của nền dân chủ Mỹ. Nhiều thập kỷ trước khi nó thành công, họ đã vô tình nuôi sống cuộc đấu tranh dân quyền. Giải pháp cho vấn đề này sẽ là tinh túy của Hollywood, và do đó là tinh túy của Mỹ - sự kết hợp giữa kiểm duyệt và tuyên truyền sẽ xóa bỏ “miễn phí, trắng và 21” khỏi các bộ phim, khỏi đời sống công chúng và gần như thậm chí khỏi ký ức quốc gia.

Câu nói này xuất hiện vào khoảng năm 1828, khi quyền sở hữu tài sản bị loại bỏ như một điều kiện tiên quyết để có quyền bầu cử và các cử tri chỉ cần là người tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi (và cũng không cần phải nói, nam giới). Lẽ ra, điều này đã chết với việc thông qua tu chính án thứ 15 vào năm 1870, nhưng tất nhiên sự phân biệt chủng tộc còn mạnh hơn luật pháp, và vào cuối thế kỷ này, các nhà lập pháp đã làm việc để đưa hai bên hòa hợp trở lại. Năm 1898, khi Louisiana đưa ra phiên bản của điều khoản ông nội , một thẩm phán khẳng định rằng luật mới chỉ đơn giản là một cách để duy trì “quyền của nam giới”, xứng đáng cho tất cả nam giới “tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi”.

Tuy nhiên, phụ nữ phải phổ biến cụm từ này — hoặc ít nhất là phụ nữ hư cấu. Các biểu hiện trong các câu chuyện tình lãng mạn bắt đầu từ năm 1856 . Sau đó, Dorothy Dix, người phụ trách chuyên mục tư vấn đầu tiên của quốc gia, sẽ tái chế nó, hướng đến phụ nữ trẻ. Nếu phạm vi ảnh hưởng chính đối với nam giới da trắng là trong phòng bỏ phiếu, thì đối với phụ nữ da trắng bị tước quyền, đó là nhà. Đặc quyền của cô tuy hẹp nhưng rất quan trọng: được chọn người đàn ông da trắng để chia sẻ nó với.

Hoặc, trong các bộ phim truyền hình Hollywood đẩy trước mã số phong bì, có bao nhiêu. Bộ phim Strangers May Kiss năm 1931 tự trình bày như một thử nghiệm về việc phụ nữ có thể có được sự lãng mạn mà không cần kết hôn hay không. Khi dì của nữ chính thúc giục cô ấy từ bỏ cuộc sống và ổn định cuộc sống, cô ấy trả lời, "Tôi tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi, và tôi biết tâm trí của mình." Như quảng cáo đã nói rõ, cụm từ này không chỉ là chìa khóa cho bộ phim mà còn cho một kiểu phụ nữ mới: Hollywood đã thực hiện hơn 100 bộ phim về “người phụ nữ sa ngã” này trong những năm 30 và 40, hầu như luôn luôn có hình phạt dành cho người phụ nữ cuối cùng.

Những kết thúc không mấy tốt đẹp này đảm bảo rằng, mặc dù cụm từ này nghe có vẻ giống như một tuyên bố độc lập (rõ ràng là không xen kẽ) đến từ bất kỳ nhân vật nào, nhưng phụ nữ “tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi” không thực sự tự do chút nào. Cụm từ này thường hoạt động như một dấu hiệu cho thấy bất cứ điều gì nhân vật đang làm sẽ không diễn ra như thế nào cô ấy muốn. Người phụ nữ trong I Am a Fugitive nghe có vẻ ngốc nghếch; cô gái trẻ trong The Glass Key (1942), người khăng khăng đòi quyền được hẹn hò với một tay cờ bạc thoái hóa và phát hiện ra anh ta đã chết; người phụ nữ trong Cry “Havoc” (1943), người biện minh cho việc tán tỉnh bạn trai của một phụ nữ khác khi biết hai người đã bí mật kết hôn; người phụ nữ Mỹ trong Foolish Wives (1922) bảo vệ việc tán tỉnh một bá tước, người tiết lộ mình là kẻ lừa đảo và để cô ấy chết trong một vụ hỏa hoạn.

Các nhân vật nữ vẫn không thể tiếp cận được với lớp của câu khẩu hiệu mỉa mai. Cụm từ kiểm tra chúng, trêu chọc chúng, có xu hướng tìm thấy chúng không cần thiết. Trong The Singer Hill (1941), một phụ nữ trẻ ban đầu được nói rằng cô ấy "tự do, da trắng và dài khoảng 21 tuổi", nhưng khi cô ấy cố gắng thực hiện ý chí của mình và bán một số mảnh đất, cô ấy bị bắt cóc, bị thẩm phán tuyên bố là không đủ năng lực trí tuệ, và , sau khi đến xung quanh, bị đánh đòn. Ngay cả khi phụ nữ không bị trừng phạt vì nói ra điều đó, họ thường có điều gì đó ngớ ngẩn khi làm như vậy, như trong vở nhạc kịch Dames năm 1934 , trong đó Ruby Keeler sử dụng cụm từ này một cách dễ thương để tuyên bố cô ấy có quyền biểu diễn trong một buổi biểu diễn trái với mong muốn của cha cô. : “Tôi tự do, da trắng và 21 tuổi. Tôi thích khiêu vũ, và tôi sẽ khiêu vũ.”

Và vì vậy, "tự do, da trắng và 21" là quyền lực bị phủ nhận nhiều như đã khẳng định. Phụ nữ sử dụng nó thường xuyên hơn vì quyền tự do của họ bị hạn chế. Đàn ông cũng sẽ sử dụng nó, bất cứ khi nào bị thách thức. Trong Người phụ nữ chắc chắn (1937), Henry Fonda kể về mong muốn của mình để lấy hết can đảm sử dụng cụm từ chống lại người cha độc đoán của mình. Trong cuộc sống thực, Henry Ford đã sử dụng nó vào năm 1919 để biện minh cho việc bất chấp những người sở hữu cổ phiếu của mình. Câu nói đó là một sự khẳng định về ý chí, về quyền của danh tính — chỉ một số người có vị trí tốt hơn để tận dụng điều này hơn những người khác. Ở một mức độ nào đó, biểu thức đã tạo ra chân lý của chính nó, tạo ra tiền tệ cho chính nó. Những đặc điểm mà nó đặt tên có sức mạnh để mở những cánh cửa; khẳng định chúng, thậm chí còn hơn thế nữa. Những người này muốn các quảng cáo từ đầu những năm 40 được đọc giống như một bản nhại lại các đặc quyền mà người da trắng ban tặng:

Các cụm từ ở khắp mọi nơi, và Hollywood, như háo hức sau đó như hiện nay để tận dụng trên một câu nói nổi tiếng , ôm chầm lấy nó. (Bạn có thể thấy háo hức như thế nào bởi thực tế là không có cuốn sách nào dựa trên những bộ phim này bao gồm câu nói này.) Thực tế, ba lần trong thời đại này, các bộ phim được dự kiến sử dụng nó như một tiêu đề. Tuy nhiên, mỗi người trong số họ , cùng với một phần tư liền kề (“Tự do, Da trắng và Tuyệt vọng”) đã được đặt lại tên trước khi xuất hiện trên một thị trường. Rõ ràng là tốt nhất nên giữ thông điệp đó bên trong.

Bước ngoặt đối với Angela Murray, nữ chính da màu trong cuốn tiểu thuyết Plum Bun năm 1928 của Jesse Redmon Fausset , đến ở lối vào của một rạp chiếu phim. Người mở đầu chấp nhận vé của Angela mà không cần suy nghĩ gì thêm, nhưng sau đó cô gái có làn da ngăm hơn, chậm hơn vài bước, bị từ chối nhập cảnh. Sau một khoảnh khắc bẽ bàng với cặp đôi bị chia cắt ở lối vào, họ cùng nhau bỏ đi. Sự việc tồi tệ đến mức Angela quyết định từ bỏ cộng đồng của mình ở Philadelphia và trở thành một phụ nữ da trắng. Sớm sống ở một thành phố mới và ở bên kia ranh giới màu sắc, câu nói sáo rỗng ập đến với cô ấy: “Cô ấy nhớ một cách diễn đạt 'tự do, da trắng và hai mốt', - lúc đó nó có nghĩa là gì, cảm giác làm chủ thế giới này, điều này nhận ra rằng những thứ khác bình đẳng, tất cả mọi thứ đều có thể. " Angela bắt đầu đi xem phim nhiều lần và lần đầu tiên có thể nhận biết được các nhân vật.

Những người sử dụng “miễn phí, da trắng và 21 tuổi” không chỉ nói với chính họ, cho dù họ có nhận ra điều đó hay không. Mặc dù các rạp chiếu đã bị tách biệt, nhưng nước Mỹ da đen cũng được Hollywood giải trí, khiến cụm từ này không chỉ là một tuyên bố cá nhân mà còn là một sự xúc phạm công chúng — và tệ hơn, đối với Angela, một sự phẫn nộ nữa làm hỏng mối quan hệ của cô với cộng đồng và chính bản thân cô.

Báo trắng không nói gì về điều này. Nhưng khi cụm từ này bắt đầu xuất hiện hết phim này đến phim khác, báo chí đen đã chú ý đến. Walter L. Lowe viết bên dưới dòng tiêu đề “Miễn phí, Da trắng và 21 tuổi” trên tờ Chicago Defender năm 1935. Ông không chắc liệu Hollywood đã sử dụng nó vì nó được coi là "hợp thời và thông minh" hay vì nó "thổi phồng thêm cái tôi của những người bảo trợ da trắng của họ," nhưng, ông tiếp tục:

Why, he wondered, would studios keep using a phrase that was “unfair,” “unsportsmanlike,” and, with “3,000,000 colored American moving picture lovers,” likely unprofitable? The saying, he concluded, “cannot substantially add anything to the pleasure of white moving picture-goers,” yet it “can detract considerably from the serenity and the pleasure of the colored people.”

Lowe wrote reservedly, hurt by the phrase but willing to reason with Hollywood, to help them see the damage they were doing. And that damage was certainly real. In a forum discussing the phrase online, a man describes his mother’s experience as a young black girl in Philadelphia when she “stormed out of [a] movie house after hearing the Ruby Keeler monologue [in Dames], promising never to watch another film with her in it again.… she was again agitated when another film-dancer she really liked, Gin Rogers, made the same statement [in Kitty Foyle]. Another one she and her friends boycotted: forever.”

As Ellen Scott shows in her fascinating new book Cinema Civil Rights, censors really were as indifferent to the feelings of African-Americans as the use of this phrase suggests. “I don’t think it matters whether the negroes like the picture or not,” reads a memo from a chief Hollywood censor in 1930 about an all-black film, Hallelujah! If they eliminated racist notes in their films, it was often as not because they knew whites would prefer not to have the reminders. Anti-lynching films could be made, but it was best to hide the violence and sometimes even cast white victims. If they feared causing offense, it was only because they feared a riot might result. To be on the safe side, they might cut lines prior to production, or they might just offer different cuts of the same movie to audiences in Harlem and downtown Manhattan.

For many members of the African-American press, this general indifference to “3,000,000 colored Americans” was all to the better. When they heard this phrase in movies, they heard Hollywood and white America simply giving the game away. In 1931, a Pittsburgh Courier writer described the use of the expression in Strangers May Kiss as a “fairly accurate index to the Nordic mentality.” The saying was used “by whites of every description and kind to illustrate their superiority and ownership of all they survey.”

“It is just this kind of a conviction” the writer concluded, that would “eventually bring down his temple of conceit upon his own head.”

Brutally honest and brutally funny, the Black press found the phrase an able tool in their task, as their FBI antagonists put it, of “holding America up to ridicule.” The gap between America’s ideals and its actuality was a persistent source of indignant glee for these papers, as the header image for a regular item in the Chicago Defender illustrates:

They approached the saying from every angle. When President Roosevelt used it about his son in 1933, the Baltimore Afro-American noted with beautiful faux-naivety: “His use of the pre-Civil War expression … isn’t particularly apropos, we take it, in these days when all Americans are free and color is no barrier to citizenship.” In 1937, after noting that “When Hollywood represents colored men on a film, nine times out of ten they are shown shooting dice,” the Afro-American was pleased to report that a recent raid had revealed that a dice game club had “a membership of 1000 New York policemen, all of them free, white, and twenty-one.” When some pre-21 white men from suburban Pittsburgh were given a slap on the wrist for causing a public disturbance and punching the arresting cops in 1958, the Courier noted that “It pays to be free, white, and from Sewickley.” (“It’s Not What you Do But Who You Are!” read the headline.)

The African-American press also used the saying to critique the contours of the privileges being asserted. Leftist critics at these papers saw the expression as another tool of capitalist oppression. “As the distance between the poor whites and the rich whites widens,” the Philadelphia Tribune noted in 1930, the former will have “nothing to look forward to in life save the dubious satisfaction of being free, white, and twenty-one,” a privilege that is “considerable when there is no other” but nonetheless serves primarily to keep them from growing “restive under exploitation.” In 1930, when two Northern college professors were beaten for attending a mixed-race Communist gathering in Memphis, an Afro-American headline noted that they were “‘White’ but not ‘Free and 21.’” And just how free were people with these traits, another story asked, if they still couldn’t “conduct the most simple bit of business with a colored man or woman”?

Not only was “free, white, and 21” undermining America’s pretensions to equality at home; it was also hurting the country on the world stage. In 1941, a writer for the Afro-American reported that, during a screening in Havana of Kitty Foyle—a movie in which that year’s best actress winner Ginger Rogers declared that she was “free, white, and twenty-one”—the translators felt compelled to omit “white” from the subtitles. Later in the movie, Kitty rejects an offer of marriage on account of her suitor’s superior social class. When he suggests there has to be something more to it, she jokes, “We’re both the same color, if that’s what you mean.” Again, the subtitles altered the line. It wasn’t so funny if the joke was on American democracy.

Hollywood’s censors just didn’t see the bigger picture, so as World War II began, the United States’ new propaganda arm, the Office of War Information, intervened. Amazingly, the US government showed greater racial sensitivity than Hollywood, repeatedly urging film producers to cut back on offensive stereotypes. But then again, the government had a better read on how bad things were. A poll of African-Americans in 1942 showed that 49 percent of respondents thought they would be treated as well or even better under a Japanese government. The OWI also knew what the Afro-American had foreseen—that films were making us look bad abroad. They insisted on cutting references to “white” and “colored” signs in films and denied foreign distribution to Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) because it depicted American mob violence. And although the military was segregated, they encouraged films that portrayed integrated ranks. The message: we didn’t need to fix our problems as much as keep them from the neighbors.

Ellen Scott told me she found no references to this phrase in the censorship records she consulted, but it seems safe to assume the government’s heightened attention to America’s reputation led to its downfall. I could only find the saying used in one movie after 1943 for the next 16 years, and that, tellingly, was a B-picture. There is also at least some record of the expression being specifically banned. In 1951, a writer for the Defender, again mocking the world’s “Caucasian minority” for “dwelling in this fool’s paradise … that he owns the world and all the peoples in it,” noted that “it was just a few years ago” that Eric Johnston, head of the Motion Picture Association of America, “issued an order forbidding screen stars to use the line: ‘I’m free, white, and twenty-one.’ Such arrogant assumptions on the part of a minority in world status is bound to bring reprisals, and Russia has seized upon this weakness in our democracy to exploit it.”

Johnston seems to have been genuine in his opposition to racism, but he was also a blacklist-making crusader against Communism who emphasized the importance of American films as propaganda behind the Iron Curtain. The African-American press had enjoyed pointing out that Adolf Hitler admired America’s discriminatory policies, and as the next great conflict got under way, there was a widespread effort to keep such evidence from view. “When so much depends on preserving and extending American democracy,” an item in the journal American Speech noted in 1949, phrases like “free, white, and 21” would have to be eliminated.

And everyone did their part. “Free, white, and 21” pretty much died.

Abandoning the phrase came almost too easily. In 1952, after moving from an independent label to Capitol records, country singer Rod Morris turned his earlier song “Free, White, and 21” into “Free, Wise, and 21.” The same substitution occurs early on in the 1953 noir, City that Never Sleeps. It was that simple. Just trade a few phonemes and the offense vanishes. The rest of the country wised up just as quickly. Newspaper usages of the saying almost completely dried up by the end of the ’60s. With Malcolm X now discussing it, the phrase was clearly too dangerous to hang onto. Suddenly, the hatred buried in the old expression was apparent not only to the African-American press but to the white papers as well; in 1963, the New York Times ran a cartoon of a wizened Klan member captioned “Free, white and going on 101.”

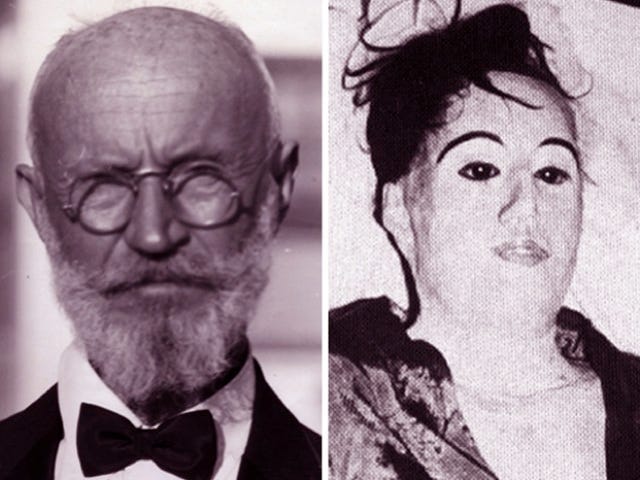

And these words that had been an innocuous feature of mainstream films a generation earlier were now being investigated on Hollywood’s outskirts. The 1963 exploitation flick, Free, White, and 21 centers on a trial over the alleged rape of a white woman by a black man. If the phrase was often about freedom of romantic choice, the film highlighted how constricted that choice really was.

It was a theme worked more artfully in the 1959 movie The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, in which Harry Belafonte emerges from five days spent in a collapsed mine to discover that chemical war has exterminated the rest of humanity—except for a young blonde woman. Yet he doesn’t see her right away; she tails him for weeks because she’s too afraid to make contact. When they finally do meet, however, they make fast friends. Things go great until a moment of tension, when a rainstorm keeps them cooped up inside together. As an argument begins, he tells her she needs to relieve her stress by keeping busy. She snaps: “I’m free, white, and 21, and I’m gonna do what I please!”

Isolated in the frame as she speaks, she re-enacts the unthinking, glib renditions of this phrase over decades of film history. Then the film cuts to Belafonte, silently registering her words, re-enacting the position of decades of those “3,000,000 colored Americans” described by Walter Lowe in 1935. Yet whereas Lowe’s message wasn’t heard by Hollywood, Belafonte soon tells her just what it meant to him: “A little while ago, you said you were ‘free, white, and 21.’ That didn’t mean anything to you, just an expression you’ve heard for a thousand times. Well to me it was an arrow in my guts!”

The chemistry between the two—and the simple fact that they are, as far as they know, the only people on the planet—should drive them to romance. But instead the legacy of the racial past keeps them apart. It goes deeper than the phrase. Yes, she seems to adore him, but Belafonte knows it took mass extinction for her to consider him as a romantic object. Although her love seems genuine, she can’t deny the truth of this.

The film, viewed then or now, is a chilling picture of the powerful reach of racism. Even after the traditional structures it infuses have been wiped away, racism lives in the damage done to those it has oppressed and the unthinking outlooks of those it has benefited. Until he hears the phrase “free, white, and 21,” Belafonte is in a state of uncertainty; he still perceives that racism is structuring this new world, but he has no evidence. The statement thus proves at once liberating and demeaning. He knew white supremacy wouldn’t just disappear that easily; he has just had that reality confirmed. The phrase itself is just a bland cliché, and he can call it such—but it nonetheless exposes a network of assumptions, a connection to a more dangerous, more explicitly racist past, that had been submerged in this new world.

Today, “free, white, and 21” is barely heard. It has no place in public life, no place in movies, except the occasional one set in the past. You can find vestiges on Twitter, usually from young women hearing it from an elder and apparently thinking it’s just their quirky ways and not the remnants of a way of life. But it’s basically dead. It was too dangerous. It made America look bad overseas and whites look bad domestically. Now it’s no longer around to do such harms, which is a sign of racial progress, but also, like any sign, distinct from the thing itself. Racism is rarely so brazen any more.

It’s a lot easier to kill off a phrase than change the system that gave it life. We can lower a racist flag, but it’s harder to get rid of the sentiments that raised it. “Free, white, and 21” lasted a hundred years after it had any official legal meaning. Why should we expect it to die just because the words have?

Andrew Heisel is a writer living in New Haven, CT. Follow him @andyheisel.

Images from MGM, the Chicago Defender, the New York Times, American International Pictures. Video by Andrew Heisel